以色列军队是如何逆向“实践”后现代哲学的?

文 / 埃亚勒·魏茨曼(Eyal Weizman) 译 / Revmira、星原

2021-05-25 15:51

本文是基于我在2002年以色列的“防卫盾牌行动”(Operation Defensive Shield)入侵巴勒斯坦地区后,对以色列军事人员和巴勒斯坦活动家进行的几次采访。[1]通过这些采访,我将尝试在下文中对武装冲突和建筑环境之间的新兴关系进行反思。当代城市武装行动是在一个构建的、真实的或想象的建筑中,通过对空间的破坏、构建、重组和颠覆来进行的。因此,城市环境必须被理解为不仅仅是冲突的背景,也不仅仅是冲突的结果,而是陷入了在其中运作的力量之间复杂而动态的反馈关系之中——无论是当地居民、士兵、游击队、媒体还是人道主义机构。在冲突和空间之间出现的关系的指示物,是重新定义了与“墙”的物理/建筑元素间的关系的新城市战争策略。在巴以冲突的背景下,墙已经失去了其传统的概念上的简单性和物质上的不确定性。因此在不同的规模和场合下,墙或被转化为灵活的实体,对不断变化的政治和安全环境做出反应;或作为可渗透的元素,实际上可以被抵抗力量和安全部队通过;或作为透明的媒体,士兵现在可以透视它,也可以通过它射击。因此,墙壁不断变化的性质将建筑环境转变为一个灵活的“前沿地带”,它是临时的、偶然的,而且永远不会完整。

这篇文章旨在扩大我们对城市行动的经验和理论知识,以加强对巴以冲突和更广泛的此类行动中的潜在政治和人权批评。通过研究军方自己的语言,以及他们声称对发展新战术至关重要的理论基础——这一基础通常在批判和后现代理论中寻找,包括德勒兹和加塔里、巴塔耶和情境主义者等人的著作——本文将试图探索军事思想家使用这些理论工具意味着什么,特别是因为,这些工具正是反对压迫的批判经常用以表达自身的那些工具。

1. 逆向几何学

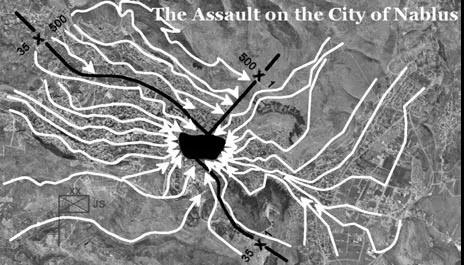

我想在这里展示的第一段摘录,来自我对以色列国防军伞兵旅旅长阿维夫·科哈维(AvivKokhavi)的采访。像其他现役军人一样,科哈维被派去完成大学学位,他计划学习建筑学,但最后却在耶路撒冷希伯来大学学习哲学。[2]科哈维负责2002年4月以色列国防军在纳布卢斯老城和旁边的Balata难民营的行动,这是以色列称为“防卫盾牌”的大型行动的一部分。他告诉我,以色列国防军是如何构想这次攻击的:

我们决定......以一种不同的建筑学角度看这个空间......你看的这个空间,你看的这个房间,只不过是你对它的解释。现在,你可以扩展你的解释的界限,但不是以无限的方式。毕竟,它必须受到物理学的约束——它包含建筑物和小巷。问题是:你是如何解释小巷的?你是像每个建筑师和每个城市规划师那样把小巷解释为一个可以走过的地方,还是把小巷解释为一个禁止走过的地方?

这只取决于解释。我们把小巷解释为禁止走过的地方,把门解释为禁止通过的地方,把窗户解释为禁止看的地方,因为小巷里有武器在等着我们,门后有诱杀装置在等着我们。这是因为敌人以传统的、经典的方式解释空间,而我不希望服从这种解释,落入他的陷阱。我不仅不想落入他的陷阱,我还想让他大吃一惊!这就是战争的本质。我需要获胜。我需要从一个意想不到的地方出现。而这正是我们试图做的。这就是我们选择穿过墙壁的方法的原因......就像一条向前吃的虫子,出现在外面,然后消失。因此,我们在意想不到的地方从住宅的内部移动到外部,从后面迂回打击在角落里等待我们的敌人......因为这是第一次[在这样的规模上]执行这种方法,在行动本身中,我们正在学习如何根据相关的城市空间来调整自己,以及如何根据我们的需要调整相关的城市空间。......我们把这种[穿墙]的微观战术实践变成了一种方法,而运用这种方法,我们就能以不同的方式解释整个空间!......

我当时命令我的部队:朋友们!这种事情用不着考虑!没有别的办法移动了!如果至今你们还习惯于沿着道路和人行道移动,那现在就把它忘了吧!从现在开始,我们都要穿墙而过!

在其他地方,科哈维将这种穿过墙壁和跨越城市纵深的机动性称为“逆向几何学”,他将其解释为“通过一系列的微观战术行动,来重新组织城市句法(urban syntax)”。[3]他的士兵没有使用构成城市秩序的街道、道路、小巷和庭院,也没有使用构成建筑秩序的外门、内部楼梯间和窗户,而是穿过界限墙进行水平移动,并通过在天花板和地板上炸开的洞进行垂直移动。因此,通过墙壁、天花板和地板在城市的固体结构中的三维运动,重新解释了建筑和城市的句法,使之短路并重新组合。运动成为空间的组成部分——它跨越而不是服从于墙壁、边界和法律的权威。

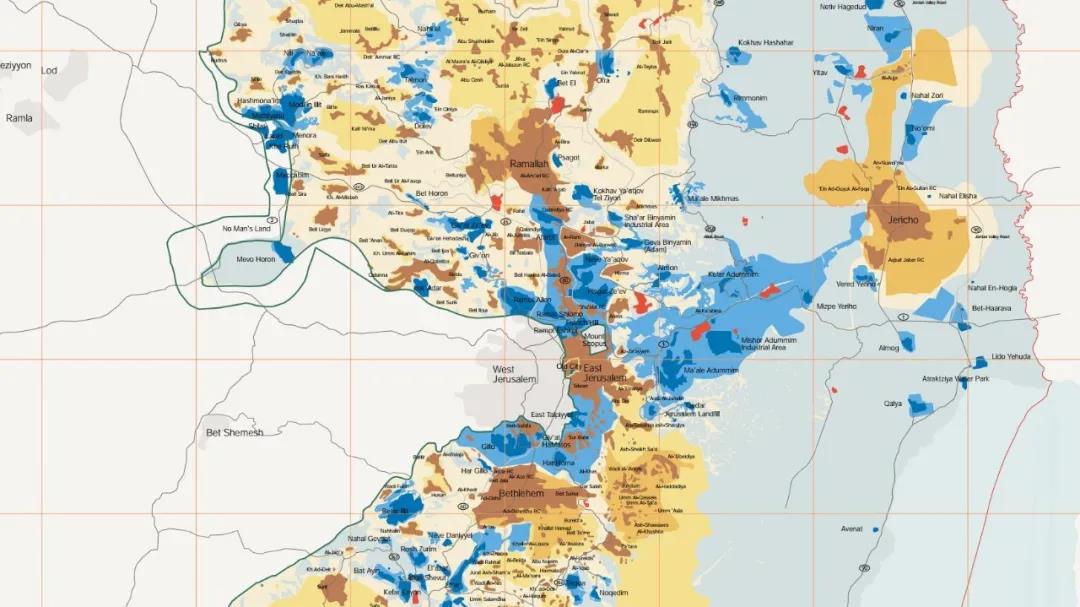

法证建筑的新项目,Conquer and Divide:The Shattering of Palestinian Space by Israel

这一策略在行动开始后的几天的制定,是为了应对巴勒斯坦抵抗力量在纳布卢斯(Nablus)和巴拉塔(Balata)的加固和组织。纳布卢斯的100-200名游击队员种含有所有巴勒斯坦武装组织的成员,他们一直在用装满混凝土的油桶、战壕和成堆的垃圾和瓦砾来阻挡通往老城和巴拉塔的所有入口。街道和小巷沿途布满了简易爆炸物和油箱。面向这些路线的建筑物的入口处也有诱杀装置,一些突出的或具有战略意义的建筑物的内部也有。营地深处组织了几个独立的小队,某个由大约15名战士组成,配备有AK-47、RPG和炸药,每个小队都围绕另一条主要路线或道路交叉口。在整个战斗过程中,奔跑者会让不同的小队保持信息和补给。

在为行动做准备时,科哈维告诉他的士兵:

他们(巴勒斯坦人)已经为一个战斗场面搭建了舞台,他们希望我们在攻击营地时,服从他们确定的逻辑......以老式的机械化队形,排成凝聚力强的队伍和大规模的纵队,符合街道网络模式的几何顺序。[4]

科哈维接到的命令是根据事先拟定的约300人的名单来逮捕或杀死“恐怖分子”,并恐吓平民以防止他们与抵抗组织合作。[5]纳布卢斯的行动始于2002年4月3日,当时科哈维的部队切断了整个城市的电力、电话和水的连接,在山上和周围的高楼设置了狙击手和观察哨,并将城市及其周围的营地封锁起来并形成一个包围圈。[6]然后,大量的小型军事单位同时从各个方向进入营地,通过墙壁而不是通过预期的路线移动。[7]科哈维对他的士兵下达的作战命令是:

我们将在白天完全隔离营地,给人留下即将开展系统性围剿行动的印象......[然后]我们将采用分形机动(fractal manoeuvre),从各个方向和各个层面同时涌向营地……每个单位在其行动方式中都要体现出总体演习的逻辑和形式。

我们在建筑物中的行动会把[叛乱分子]推向街道和小巷,在那里我们将捕杀他们。[8]

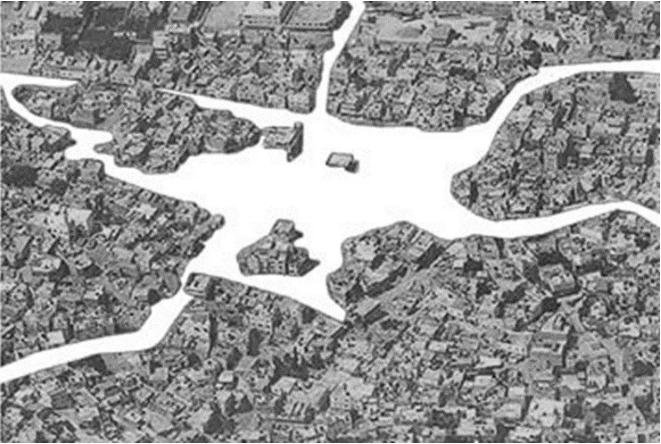

根据巴勒斯坦学者努尔汗·阿布吉迪(Nurhan Abujidi)在战后进行的一项调查,纳布卢斯老城中心有一半以上的建筑物被强行穿过,在墙壁、地板或天花板上开了1到8个口子,形成了几条杂乱无章的交叉路线,无法用简单的线性进程来解释。[9]

穿墙并不应该被误认为是一种相对“温和”的战争形式。以下是对事件顺序的描述:士兵们在墙后集结。他们用炸药或大锤子砸出一个足以通过的大洞。在他们冲过墙之前,有时会有眩晕手榴弹或几声乱枪打入通常是毫无防备的私人客厅。当士兵穿过界限墙(party wall)后,被入侵的家庭成员被集合起来,并被锁在其中一个房间里,他们不得不呆在那里,有时要呆上几天,直到行动结束,往往没有水、厕所、食物或药品。根据人权观察和以色列人权组织Bʼtselem的说法,有数十名巴勒斯坦人在这种行动中死亡。如果穿墙行动被军方说成是对传统城市战争的肆意破坏的“人性化”回应,以及对杰宁(Jenin)式破坏的“优雅”替代(译者注:杰宁是2002年以色列军队在进攻过程中严重毁坏的一座巴勒斯坦难民营),这是因为它造成的破坏往往隐藏在房屋内部。在巴勒斯坦,就像在伊拉克一样,战争对家庭这一私人领域的意外渗透被视为最深刻的羞辱和创伤的形式。以下是巴勒斯坦监测组织工作人员Sune Segal于2002年11月收集的一名名为阿伊莎(Aisha)的巴勒斯坦妇女的证词摘录:

想象一下——你正坐在你熟悉的客厅里,这是一家人晚上吃完饭后一起看电视的房间......突然,那堵墙在震耳的轰鸣声中消失了,房间里充满了灰尘和碎屑,透过墙一个又一个士兵大叫着发号施令。你不知道他们是否会攻击你、霸占你的家,还是说你的家只是在他们前往其他地方的路上。

孩子们在尖叫,惊慌失措……甚至可以想象一个五岁的孩子在四、六、八、十二个士兵面前所经历的恐怖,他们的脸被涂成黑色,冲锋枪指向各处,天线从他们的背包里伸出来,使他们看起来像巨大的外星虫子,从那道墙中轰然穿过!

阿伊莎指着她家的另一面墙,上面有一个内置的书柜:这就是他们离开的地方。他们炸毁了这面墙,继续向我们邻居的房子走去。

魏茨曼和贝塞莱姆制作的西岸犹太人定居点互动地图。

2. 学院

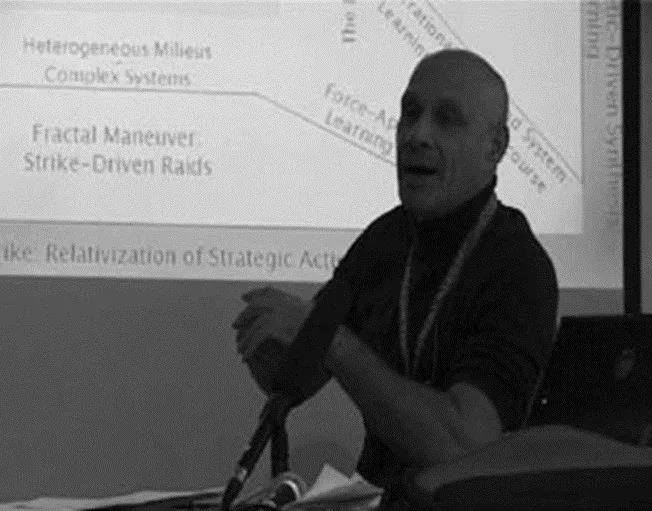

西蒙·纳维(Shimon Naveh)是以色列军队的一名退役准将,是以色列国防军所谓的“行动理论研究所”的所长。他大约60岁,他的光头和某种程度上的身体相似性使一些人把他称为“磕了药的福柯”。该研究所成立于1996年,是一个培训高级军事人员的理论实验室。科哈维就是其学员之一。研究所的阅读清单之一是由许多建筑学理论(主要来自1968年左右)、以及城市研究、系统分析、心理学、控制论、后殖民主义和后结构主义理论等方面的工作组成。当我采访他时,纳维解释说:

我们就像耶稣会的人。我们试图教导和训练士兵思考......我们阅读克里斯托弗·亚历山大,你能想象吗?约翰·福雷斯特,和其他建筑师。我们在读格雷戈里·贝特森,我们在读克利福德·格尔茨。不仅是我自己——我们的士兵,我们的将军们都在思考这些类型的材料。我们已经建立了一所学校,我们已经开发了一个课程,培训行动建筑师。[11]

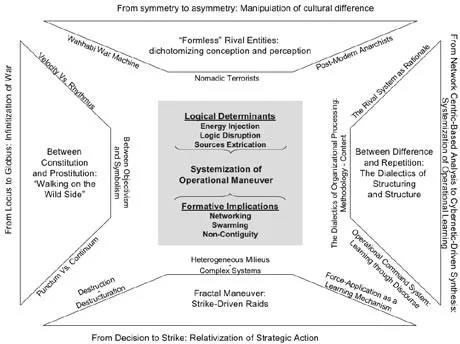

根据纳维的说法,这个研究所在以色列国防军和其他军队中是独一无二的。然而,它构成了地理学家斯蒂芬·格雷厄姆(Stephen Graham)所说的“阴影世界”的决定性部分,这个世界由军队的城市研究机构和培训中心组成,目的是为了重新思考城市地区的军事行动。根据西蒙·马文(Simon Marvin)的说法,这个“影子世界”目前负责的城市研究项目比所有大学项目加起来还要密集,而且资金充足。[12]在特拉维夫的“领土-生活”展览中,[13]Naveh展示了一张类似于“对当方阵”(Square of Opposition)的幻灯片,该幻灯片描绘了有关军事和游击队行动的某些命题之间的逻辑关系集合。不同的角落包含这样的标题:“差异和重复——结构化和结构的辩证法”;“无形的对立实体”;“分形机动”;“速度与节奏”;“瓦哈比战争机器”;“后现代无政府主义者”;“游牧的恐怖分子”——这些短语主要参考德勒兹和加塔里的作品。[14]

在之后的采访中,我问纳维:“为什么读德勒兹和加塔里?”

纳维:《千高原》中的几个概念对我们很有帮助......使我们能够以一种用别的方法无法做到的方式解释当下情况。它把我们自己的范式问题化……最重要的是他们指出了“平滑”(smooth)和“条纹”(striated)空间概念之间的区别......[这相应地反映了]“战争机器”和“国家机器”的组织概念……在以色列国防军中,当我们想把一个空间中的行动当成是没有边界的时候,经常使用“空间平滑化”一词。我们试图以边界不影响我们的方式来创造行动空间。巴勒斯坦地区确实可以被认为是“条纹的”,因为它们被围栏、墙壁、沟渠、路障等所包围......我们想要对抗传统的、老式的军事实践中的“条纹空间”。我们想用一种允许在空间中移动、跨越任何边界和障碍的平稳性来对抗传统的、老式的军事实践[大多数以色列国防军部队目前的行动方式]。我们不是根据现有的边界来控制和组织我们的部队,而是要穿越边界。[15]

作者:穿墙行动是其中的一部分吗?

纳维:在纳布卢斯,以色列国防军将城市战斗理解为一个空间问题……穿墙而过是一个简单的机械解决方案,可以将理论和实践联系起来。穿越边界是对“平滑性”条件的定义。[16]

这也与该研究所制定的涉及一般政治问题的战略立场相吻合。纳维支持以色列从加沙地带撤军,以及在2000年从黎巴嫩南部撤军之前支持这一行动。他也同样赞成从约旦河西岸(West Bank)撤军。事实上,他的政治立场与以色列人所说的犹太复国主义左派一致。他的投票在工党和梅雷兹党之间交替进行。他的立场是,以色列国防军必须放弃在被占领地区的存在,来换取在这些地区自由通过的可能性,或者在那里产生他所谓的“效果”,也就是“展开军事行动,如空袭或突击队袭击,在心理上和组织上影响敌人”。因此,“无论他们(政治家们)能达成什么共识——他们把围墙放置在哪里,对我来说都没有问题......只要我可以越过这道围墙。我们需要的不是在身处那里,而是需要......在那里采取行动。撤军并不是‘故事的结局’。”

3. 蜂群

的确,很多年来我一直都想在地图上推进自己的生命疆域。我一开始预想的是一张普通的地图,现在倾向于参谋部用的市中心地图,假如这种地图存在。这种地图无疑不存在,由于我们不知道未来战争的战区如何划分。——瓦尔特·本雅明[17]

为了理解在巴勒斯坦城市地区的军事行动,有必要解释以色列国防军如何解释现在已经很熟悉的“蜂群战术”原则——自军事变革(注:Revolution of Military Affairs;指上世纪90年代开始的数字化、精确化的军事学说革命)开始以来,这个词已经成为军事理论中的一个热门词汇。在采访中,科哈维解释了他理解这一概念的方式:

一个国家的军队,如果它的敌人是分散的零星帮派网络......就必须把自己从直线、单位、团和营的线性模型的旧概念中解放出来......而使自己变得更加分散,具有灵活性和蜂群性......事实上,它必须根据敌人的隐蔽能力来调整自己……蜂群在我看来就是同时从大量的节点到达目标——如果可能的话,从360度。

在另一场合,他提到蜂群没有形状,没有前部、后部或腹部,而是像云一样移动,应该用位置、速度和密度来衡量,而不是用功率和质量。[18]这一原则认为,解决问题的能力是在相对不复杂的行动者(蚂蚁、鸟、蜜蜂、士兵)的互动和交流中发现的,没有(或只有极少的)集中控制。因此,“集群智能”(Swarm Intelligence)指的是一个系统的整体综合智能,而不是指其组成部分的智能。通过互动和适应突发状况,系统作为一个整体会自发学习。[19]

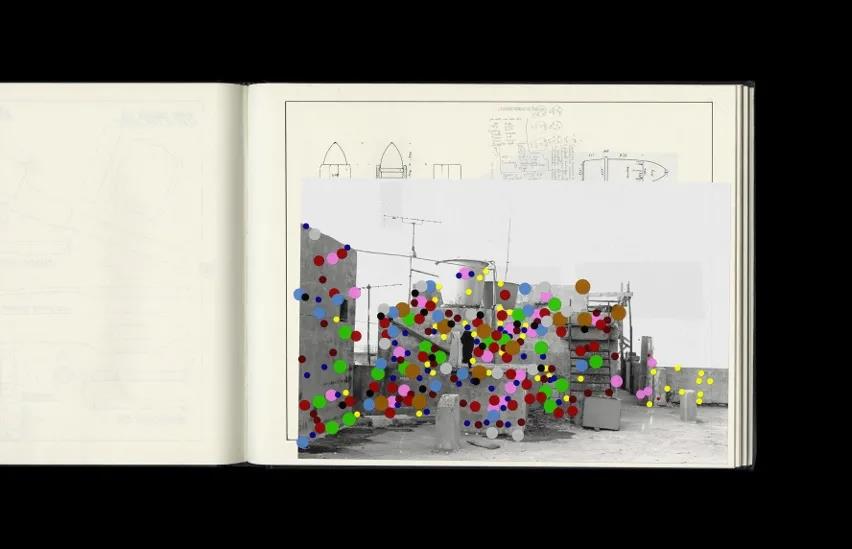

Walid Raad - The Atlas Group(1989-2004), Let's Be Honest, the Weather Helped, 1998, photo credits Carré d'Art–Musée

根据西蒙·纳维的说法,蜂群体现了“非线性”的原则。这一原则在空间、组织和时间方面都是很明晰的。

在空间方面——线性作战依赖边界线的行动权威(operational authority),也依赖前线、后方和纵深之间的区别,军事纵队从外部进入城市(纳维称之为“将机动性服从欧几里得逻辑”)[20]相反,蜂群战术试图以“非线性”的方式进行作战并从外部进入城市——寻求从内到外、从各个方向同时进行攻击。运动路线不是直线,而是倾向于以狂野的“之”字形前进,以迷惑敌人。传统的演习模式以欧几里得的简单几何学为特征,在此被转化为复杂的分形几何学。

在组织方面,蜂群没有固定的线性或垂直的指挥和通信链,而是作为多中心的网络进行协调,具有水平的通信形式,其中每个自主的(autarkic)单位可以与其他单位进行通信而不需要通过中央指挥。因此,战斗单位的物理凝聚力被一个概念性的凝聚力所取代。根据纳维的说法,“这种演习形式的基础是打破所有的等级制度,由战术层面的指挥实践来协调讨论。这是一种几乎没有规则的狂野话语”。正如科哈维在上文所提到的,其中的分形逻辑表现为:“每个单位......都在其行动模式中反映了总体演习的逻辑和形式”。正如Naveh所说:

尽管在情报方面投入了很多,但城市中的战斗仍然是、而且是愈发是出乎意料和混乱的。战斗不可能有剧本。指挥部无法掌握全局。行动的决定必须基于机会、突发事件和机遇,而这些决定必须在实地实时作出。

该理论认为,通过将决策的门槛降低到直接的战术层面,并通过鼓励基层的主动性,蜂群的不同部分可以为不可预测的遭遇、快速发展的局势和变化的事件——自克劳塞维茨以来被称为“摩擦"的不确定性形式——提供答案。[21]

在时间方面,传统的军事行动是线性的,因为它们试图遵循一个确定的、有结果的事件序列,体现在“计划”的理念中。在传统的军事计划中,“计划”的概念意味着行动在某种程度上是以先前行动的成功实施为前提的。战斗的进展是分阶段的。相比之下,“蜂群”应当会引起同时的行动,但这些行动并不相互依赖。战斗计划的叙述被“工具箱”方法所取代。[22]根据这种方法,各单位获得了处理若干给定情况和情景的工具,但不能预测这些事件实际发生的顺序。

Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, History of a Pyromaniac Photographer, #19, First part of the Wonder Beirut Project 1997–2006, C print on aluminium with face mounting. Courtesy In Situ Fabienne Leclerc(Paris), CRG Gallery(New York), The Third Line(Dubai)

因此,通过蜂群机动,军队试图打破其几何学甚至地形学上的特点,而采用拓扑学上的特点,将自己重新组合成一个网络,这实际上是受到游击队和恐怖分子战术的启发。这种模仿行为是基于军事理论家John Arquilla和David Ronfeldt所阐述的假设,即“需要用一个网络来对抗一个网络”。[23]对于Naveh来说:

蜂群的概念与军事上将战斗空间理解为一个网络的尝试相吻合——城市是一个非常复杂的相互依存的网络系统。而且,城市战役发生在两个网络——作为网络的军队和作为网络的敌人——是处于在空间上重叠的领域中。战斗必须被理解为一个动态的力量关系场,其中士兵、物体、行动和空间必须被视为与其他空间、物体和行动有着持续和偶然的关系……这些力量关系意味着交叉、融合、合作或冲突。这种关系性必须被看作是军事空间性的核心特征。

这或许可以解释军队对德勒兹和加塔里等理论家提出的空间模式和行动方式的极大兴趣,而这二位哲学家自身也从游击队组织和游牧战争中获得了灵感。[24]

(右)加塔里;(左)德勒兹

作为现代城市冲突和游击战历史上的典范,巴黎公社的保卫者与阿尔及尔、顺化、贝鲁特、杰宁和纳布卢斯的保卫者一样,通过住宅、地下室和庭院之间的开口和连接,以及通过小路、秘密通道和活板门,以松散协调的小团体在城市中游走。由于无法控制分散在斯大林格勒的苏联红军抵抗区,瓦西里·伊万诺维奇·崔可夫(Chuikov)也同样放弃了对其军队的集中控制。其结果后来被分析为一种“突发行为”,即独立单位之间的互动创造了一个所谓的“复杂适应系统”(complex adaptivesystem),使军事行动的总效果大于其组成部分的总和。[25]由几位军事理论家在战间期发展起来的“机动战”,在第二次世界大战的欧洲战场种被德军和盟军都实施过,它也是基于增加自主权和主动性等原则。[26]同样,以色列建筑师沙龙·罗特巴德提醒我们,在每一场城市战役中,出于当地战术的需要,都会重新发明穿墙作战的方法。[27]这种战术最早见于托马斯·比若(Thomas Bugeaud)元帅的《街道与房屋战争》,是在巴黎工业革命时期以阶级为基础的城市战斗中采取的反叛乱战术。[28]比若建议不要从正面攻入街垒,而是从侧面进入,沿着横跨界限墙的“地面隧道”进行“鼠洞”,然后从侧面突袭街垒。在街垒的另一边,路易-奥古斯特·布朗基(注:Louis-August Blanqui,法国社会主义革命者)在十年后将这一微观战术方法写进了他的《军队须知》。[29]对布朗基来说,路障和老鼠洞是用来保护自治的城市飞地的互补要素。这一点是通过对城市语法(urban syntax)的完全颠覆。运动的元素——铺路石和马车——变成了静止的元素(路障),而现有的静止元素——墙壁——变成了路线。城市中的战斗,以及为城市而战的战斗,与对城市的阐释是等同的。

然而,尽管这里有一些相似之处,但当代的蜂群战术不仅取决于穿墙移动的能力,还取决于独立部队在城市纵深中的定位、导航和与其他部队协调的技术能力。在巴拉塔的行动中,7000名以色列国防军士兵在营地和后来的老城中移动——科哈维将此称为“侵染”(infestation)——几乎不踏足街道。为了进行这样的演习,每支部队都必须了解自己在城市地理中的位置,与其他部队和作战空间内的敌人的相对位置,以及与整个演习逻辑有关的位置。在我对一名以色列士兵的采访中,他这样描述同时进行的战斗的开始:

我们从来没有离开过建筑物,完全是在住宅之间前进......在一个由四座住宅组成的街区中移动需要几个小时……,我们所有的人——整个旅——都在巴勒斯坦人的住宅中,没有人在街上……,在整个战斗中,我们几乎没有冒险出去……,谁在街上没有掩护,就会被射杀。我们在这些建筑物内划出的空间里设立了我们的总部和睡眠营地......这使得我们无法制定战斗方案或单轨的计划来贯彻执行。[30]

事实上,城市战争是最典型的后现代战争。在城市现实的复杂性和模糊性中,人们对有逻辑的结构、单一轨道和预先计划的方法的信念消失了。平民变成战斗员,战斗员又变成平民。身份的变化和性别的变化一样快;角色从女人变成了武装的男人,就像一个卧底的“阿拉伯化”以色列士兵或一个伪装的巴勒斯坦战士从衣服下面取出一挺机枪一样快。对于一个在这场战斗中被抓到的巴勒斯坦战士来说,以色列人无处不在:后面、侧面、右边和左边。[31]由于巴勒斯坦游击队战士有时也会以类似的方式,通过预先计划好的空隙进行机动作战,因此大多数战斗都发生在住宅内。有些建筑就像千层蛋糕,巴勒斯坦人被困的楼层上下都有以色列士兵。

4. 军事理论

我问纳维,批判理论对于他的教学与训练有何重要之处。他回答道:

我们运用批判理论主要是为了批判军事建制(military institution)本身——它的概念基础固定而且笨重……理论对于我们来说是重要的,这是为了阐明在现存的范式和我们想要达到的目标之间存在的那个鸿沟……没有理论,我们就无法理解在我们身边发生的不同事件所具有的意义,如果不是使用了理论的话,这些事件看起来就会是没有关联的。

在关于另一点的采访上,他又回到了教育问题上:

我们之所以建立这个学院,是因为我们相信教育,而且也需要一个学校来发展我们的理念……目前为止,学院已经对军事产生了巨大的影响……它已经成为了军事中的一个颠覆性的节点(subversive node)。通过对几名高级军官进行训练,我们使系统(以色列国防军)中充满了颠覆性的行动者(agents)……他们会提出质疑……一些身居要职的人在谈到德勒兹或者屈米时完全不会感到尴尬。

我问他:“为什么读屈米(Tschumi)?”

纳维:在屈米的著作《建筑与离析》中体现了离析(disjunction)的观念,这一观念对于我们来说有很大价值…屈米有另一种认识论的进路——他想要破除单一视角的知识和中心化的思维。他通过各种不同的社会实践,以不断移动的视点来看待世界……屈米创造了一种新的语法——是他形成的观念构成了我们的思想。[32]

我:屈米……?为什么不学德里达和解构呢?

纳维:我们的将军都是建筑家……而屈米对行动,空间及其表征之间的关联加以概念化。《曼哈顿手稿》(注:屈米提出的一个计划,它记录了纽约中央公园发生的一起谋杀案)给了我们以工具,使我们制定行动计划的方式完全不同于在地图上画简单的线条。它提供了策划行动的可用符号。德里达对于我们来说有一点过于隐晦了。我们同建筑家之间有更多的共鸣——我们结合了理论与实践。我们可以阅读,但是我们也明白如何建造,如何摧毁,有时是如何杀戮。

伯纳德·屈米,著名建筑评论家、设计师。图源:Architectual League of New York

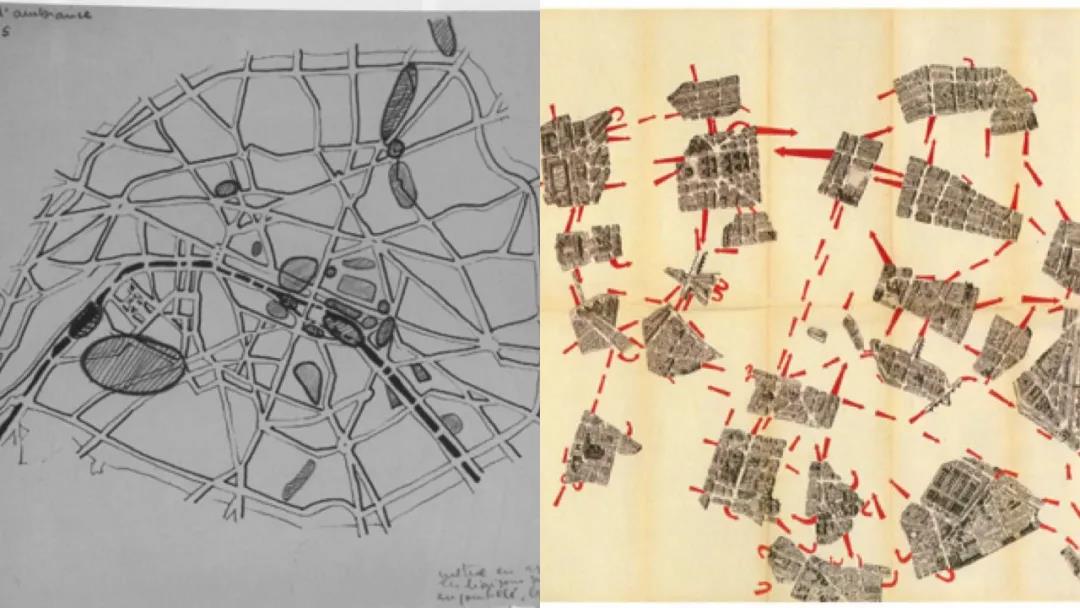

除了上述的理论之外,纳维还提到了城市理论中的一些典型元素,譬如情境主义的漂移(dérive)的实践——这是一种在城市中游荡的方法,它基于情境主义者的心理地理学(psychogeography)——以及异轨(détournement)的实践——对已经建立起来的或是被占有了的建筑物进行改造,使其服从于同其设计职能不同的目的。这些当然是居伊·德波(Guy Debord)和情境主义国际中的其他人物所构想出的,他们将其作为拆解资本主义城市中既已构成的等级结构,打破私人与公共、内部与外部、使用与功用之间的边界的一般策略;[33]他们将私人空间替换为一种“无边界的”公共表面。纳维引述了乔治·巴塔耶的著作,有些是直接的引用,有些是从屈米的著作中引用的,在其中,巴塔耶把握到了攻击建筑的欲望。巴塔耶自己的战斗号召的本意在于,废除战后秩序中僵化的理性主义,逃离“建筑化的拘束衣”,并将个人被压抑的欲望解放出来:“建筑的纪念碑式分泌物现在真正地支配了整个地球,将奴性的诸众聚集在它们的阴影之下,强加给人们赞美与惊奇、秩序与束缚,对这样的建筑加以攻击,可以说,必然是对人的攻击。”[34]对于巴塔耶、屈米和情境主义者这样的人来说,城市的压抑性力量被在其中穿梭与跨越的运动所颠覆。在战后的年代,当我在这里所提到的这些“左翼”的理论观念得到发展时,对于主权国家结构维护或促进民主的能力的信心不断减弱。那时的“微观政治”(micro-politics)是一种尝试,它试图在身体、性与主体间性的亲密层面上,构成精神和情感上的游击战士。个人的东西成为了颠覆性政治的要素。如此一来,它就是一种从形式上的国家机器逃离到私人领域的策略,后来又向外得到了扩展。这些理论被构想出来是为了违犯城市中确立起来的既有的“布尔乔亚秩序”——坚硬而固定的墙壁在物质与形式上具现化了这一压抑。但在这里,这些方法被加以规划,其目的却是为了构想对一个“敌方”城市展开战术进攻的形式。人文学科的教育常常被认为是反对帝国主义的最好的、持续性的武器,却为帝国主义所采用,当作自身的武器。

Guy Debord 1957年的巴黎的心理地图(Psychogeographique de Paris. Speech on the Passions of Love)

本文的目的并不是去纠正军事思想家在对于特定理论的使用和阐释中的所犯下的错误和夸大其词的弊病。很明显,纳维想要突出他作为对于颠覆性的理论的“颠覆者”角色,同时也享受这一点。在交流中,他经常提出一些令人发指的主张。他重复了一个事实,那就是他的工作和他的理论实践的最终目的就是杀戮:“你有读过那本关于‘亲密杀人’的书吗?……为了杀人,我们必须来到我们想要杀死的人身边…我们绝不是想要占领一个地区,然后便离开。”此外,在军事上运用理论当然不是什么新鲜事。军人哲学家的形象已经是以色列军事史上的老调重弹。在20世纪60年代,学术教育就已经成为了军事职业的一部分,许多高级军官从美国留学归来,在一起讨论斯宾诺莎,通过斯宾诺莎的“广延”概念来描述战争空间,特别是1967年六月战争中的军事占领。所以,在这一点上,这不是归咎于理论的问题。我们需要的是承认和理解他们所使用的左翼理论中的特殊方面,他们使用这些理论不是为了颠覆权力,而是为了投射权力。当我向纳维本人询问他所使用的理论的意识形态基础时,他回答道:

马克思主义意识形态具有一定魅力,甚至有着某种价值,但我们必须把这一点同我们能够从中提取出来用于军事用途的部分区分开来。理论并不仅仅是为了求取乌托邦式的社会政治理想,我们可能会喜欢这种理想,也有可能厌恶它,但理论更是基于一种方法论,它试图扰乱和颠覆现存的政治、社会、文化或军事秩序。理论的破坏性能力(在别处他用了“虚无主义”一词)才是理论中为我们所喜爱和使用的那个方面……这种理论和它的社会主义理想并不是完全绑定的。

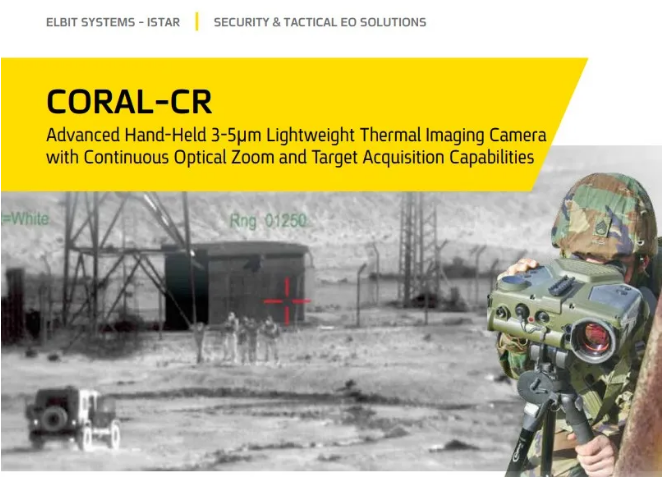

5. 透明之墙

特别地强调城市区域中军事行动,是为了发展未来旨在进行“壁的去壁化”(un-walling of the wall)的技术和技巧(用戈登·马塔-克拉克的话来说)。[35]除了在物理上突破墙壁之外,一些新的方法也被设计出来,使得士兵能够看到和射击墙壁的另一侧。一个名为科迈罗(Camero)的以色列公司开发了一种手持式跨壁视觉机器,结合了热成像和超宽带雷达,能够和医用超声波一样产生坚固物体后面的空间中的生命体的三维渲染图像。[36]这些图像将人呈现为模糊的热源,在抽象的透明介质上浮动着,一切坚实的东西——墙壁、家具、目标——都被熔于这一介质之中。能够穿透墙壁的特殊子弹也被研制出来,这种子弹无需弹头偏转,使得穿壁的视觉和射击能力得到了完善。如此一来,穿墙雷达会在未来的军事实践与建筑之间的关联中产生根本性的影响。它的未来发展将会使其具有将一切建筑环境以及生命变得透明可见的能力,它会将城市景观如同纱布般揭起,使固态建筑有如蒸发殆尽。使一切拥有“字面意义上的透明性”(transparency)的工具,它构成了一个这样的世界的主要组成部分:一个军事上的幽灵般的幻想世界,这个世界中的一切都进入了没有边界、没有束缚的流动性,城市成为了可航行的空间,成为了一片海洋。通过设法看见不可视者,使时空坍塌,并在空间中移动,军方力求将当代的技术与(几乎是当代的)理论提高到形而上学的层次——就是要从物理现实的此时此地中超越出来。

这一点同样与造成“可控的”破坏(controlled destruction)的技术相关。2002年4月,在国际上爆发了对杰宁(Jenin)难民营被毁的抗议后,以色列国防军认为,必须进一步发展对于工兵部队的教学,提升他们的“破坏的艺术”(art of destruction),因为破坏走向了失控。在一场于特拉维夫举办的军事会议上,一名以色列的工兵军官向他来自国际各地的听众说道,“在对于建筑建造和建筑结构的研究的帮助下”,目前,“军方已经能够移除建筑物中的一层,而不会完全摧毁这座建筑,或者移除一排建筑中的一个,而不会破坏其他的建筑物。”[37]这证实了,如果不是言过其实的话,“如同外科手术一样”移除建筑物的部分是工兵对于“智能武器”逻辑的回应。以色列使用的“智能武器——比如”在“定点暗杀”(targeted assassinations)行动中使用的那些——所反而带来了更大规模的平民伤亡,是因为精确性的幻觉使军方和政界将在平民地区使用爆炸物的行动正当化了,而在那里,使用爆炸物就一定会导致对于平民的伤害——阿克萨群众起义期间,加沙每有一次有意图的杀人行动,就会导致两名平民死亡[38]。类似,“智能破坏”的空想出来的能力,以及试图施展“精密”集群战术(sophisticatedswarming),在长时段内将会带来比“传统”策略还要更多的破坏,因为这些方法以及和这些方法相关的操纵式的、亢奋的辞令,让决策者们得以频繁使用这些手段。因此,批判性审视这一方面的军事语言是至关重要的。高度亢奋的军事理论和军事技术“言论”试图将战争描述为远程的、无影响的、轻易的、快速的、激动人心的、几乎没有任何代价的(对于军方来说)。于是,暴力被当作可接受的,公众也更倾向于支持暴力。这样一来,通过进一步发展和传达新的制造战争的技术,从军事上加以解决是可接受的,这一幻觉已经被植入到了公众当中。然而,正如迄今为止无数的实例所证实了的那样,这其中也包括在巴拉塔(Balata)难民营和纳布卢斯旧城区(Kasbah of Nablus)开展的行动,城市战争的现实比军方所描绘的那样要更为肮脏和血腥。

这一点同样与造成“可控的”破坏(controlled destruction)的技术相关。2002年4月,在国际上爆发了对杰宁(Jenin)难民营被毁的抗议后,以色列国防军认为,必须进一步发展对于工兵部队的教学,提升他们的“破坏的艺术”(art of destruction),因为破坏走向了失控。在一场于特拉维夫举办的军事会议上,一名以色列的工兵军官向他来自国际各地的听众说道,“在对于建筑建造和建筑结构的研究的帮助下”,目前,“军方已经能够移除建筑物中的一层,而不会完全摧毁这座建筑,或者移除一排建筑中的一个,而不会破坏其他的建筑物。”[37]这证实了,如果不是言过其实的话,“如同外科手术一样”移除建筑物的部分是工兵对于“智能武器”逻辑的回应。以色列使用的“智能武器——比如”在“定点暗杀”(targeted assassinations)行动中使用的那些——所反而带来了更大规模的平民伤亡,是因为精确性的幻觉使军方和政界将在平民地区使用爆炸物的行动正当化了,而在那里,使用爆炸物就一定会导致对于平民的伤害——阿克萨群众起义期间,加沙每有一次有意图的杀人行动,就会导致两名平民死亡[38]。类似,“智能破坏”的空想出来的能力,以及试图施展“精密”集群战术(sophisticatedswarming),在长时段内将会带来比“传统”策略还要更多的破坏,因为这些方法以及和这些方法相关的操纵式的、亢奋的辞令,让决策者们得以频繁使用这些手段。因此,批判性审视这一方面的军事语言是至关重要的。高度亢奋的军事理论和军事技术“言论”试图将战争描述为远程的、无影响的、轻易的、快速的、激动人心的、几乎没有任何代价的(对于军方来说)。于是,暴力被当作可接受的,公众也更倾向于支持暴力。这样一来,通过进一步发展和传达新的制造战争的技术,从军事上加以解决是可接受的,这一幻觉已经被植入到了公众当中。然而,正如迄今为止无数的实例所证实了的那样,这其中也包括在巴拉塔(Balata)难民营和纳布卢斯旧城区(Kasbah of Nablus)开展的行动,城市战争的现实比军方所描绘的那样要更为肮脏和血腥。所以,我们可以认为,使用德勒兹的理论不过是一种宣传的形式吗?将理论当作仅仅是宣传而藐视它,这样做太过容易了。因为,正如“智能武器”的概念一样,这一理论在巴以冲突中既有实际的功能,又有其话语上的功能。就其实际功能而言,德勒兹的理论在多大程度上影响了军事的策略与控制,这是一个有关理论与实践之间的关联的问题,因而也颇为复杂。很明显,理论创造了新的感受力,并有助于对不同的知识领域中各自独立地涌现出来的观念加以解释和进一步的发展。就其话语而言,如果战争不是歼灭的全面战争的话,就总是敌对双方之间的一场话语。每一次军事行动都是为了同敌人交流某种东西,表露、威胁、示意。所以,关于蜂群战术、定点杀戮,以及智能破坏的言论,能够有助于军方同其敌人的交流,告诉他们,自己仅仅使用了全部的毁灭力量中的一部分。

在这一方面,一次集群行动就是一次警告:“下一次我们将会通过不受约束的残忍来减少更多的伤亡”,——正如在杰宁难民营所做的那样。[39]因而,以色列军的突袭就可以在抵抗者的心中被投射为一种“较小的恶”,是相对于军方所掌握的彻底摧毁能力的一种更为温和的选择;而如果敌人突破了暴力的可接受的程度,或是违背了某种不成文的规则的话,军方的毁灭能力就会走向释放。在军事行动理论中,军方永远不动用全面摧毁的能力是非常关键的;他们总是保存不断增加暴行等级的能力。如果没有这一相对的“限制”,恐惧和威胁就会毫无意义。

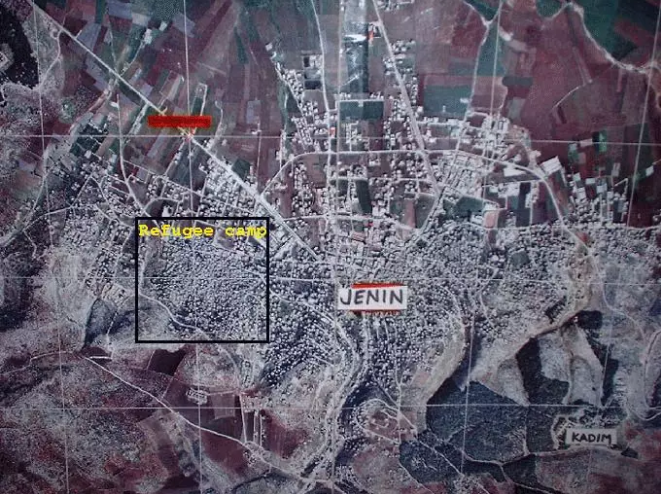

6. 移动屋墙

以色列国防军对于杰宁难民营的摧毁——在这一40000平方米的区域内有着超过四百座建筑[40]——可以说为难民营创造了一种全新的布局。在战役的结束阶段,可以看到,新的道路被开凿,现有的道路被拓宽,难民营的中心辟开了一片空地。坦克与其他军用车辆能够沿着新的和被拓宽的那些道路深入到难民营内部。事实上,对难民营中心的肆意破坏始于4月9日,当时巴勒斯坦游击队战士在难民营哈瓦辛区的一次伏击中设法杀死了13名以色列国防军士兵——游击队使整条小巷坍塌在以军士兵身上,把建筑结构作为武器。

战斗结束后,巴勒斯坦的难民营居民与联合国代表之间发生了冲突,这可能也反映出了设计同毁灭之间的关系的另一个方面。下面的信息主要基于一项影视研究项目,这一项目是纳达夫·哈雷尔(Nadav Harel)、安塞尔姆·弗兰克(Anselm Franke)和我在难民营重建期间进行的。阿拉伯联合酋长国的红新月会捐赠了约2700万美元,用来让联合国救济和工程处(UNRWA)在难民营实施一项新的总计划,并用新的住房来代替大部分被摧毁的住房。[41]这些计划的公开展示引发了一系列的冲突。简要地说,据我所知,重建计划中存在着两个有争议的问题。第一个涉及道路布局:工程处的工程师提议用以色列国防军所破坏的路径来加宽难民营的道路。九条大街被以色列国防军的坦克用作进入难民营的通道,它们被推土机所加宽,这些大街会按照新的、“加宽后的”尺寸来重建。它们从五米多一点的宽度被伸长到将近七米——刚好宽到足够让以色列坦克转向,而不会撞向房屋墙壁。在某些情况下,以色列军队只在底层进行拓宽。他们把外墙向内离原来的位置“推动”近一米,使得上面的楼层悬垂在街上。[42]尽管工程处的提案被认为是对于难民营的交通管理的一项改进,难民营的人民委员会——在其中,武装组织具有关键的影响——抗议称,拓宽道路可能会使以色列坦克轻松地驶过难民营地。[43]委员会的一名成员公开表示抗议,坚持认为“应该让以色列坦克更难,而不是更容易进入难民营”。[44]争议以工程处行使在难民营事宜上的权威,不加理会地按照“加宽”方案进行重建而告终。工程处的项目负责人,[45]贝特霍尔德·威伦巴赫(Berthold Willenbacher)在一份事后的道歉中说,重新设计的军事方面单纯是一个负面的副作用:“我们设计了一条以色列人可以让坦克通过的通道,我们本不应这样做,因为比起狭窄的小巷,武装人员逃走的机会更加渺茫。我们没有考虑到这一方面。”[46]然而,委员会的成员对我们说,他们相信这一决定是工程处有意做出的,是为了保护新修建的“资产”。

一场相关的争端有关于墙壁作为视觉障碍的性质和功能,这场争端在人民委员会本身的成员当中爆发。在难民营内的部分建筑中,小院同街道被两米高的围墙隔开。墙后面的院子是妇女和儿童玩耍和烹饪的地方。在行动期间,这些墙被以色列国防军士兵所摧毁,目的是为了暴露出可能的狙击手藏身处。第二场争论的议题是这些围墙的高度。哈马斯在人民委员会中的代表要求这些墙要低于平均的视线高度,以确保伊斯兰教的端庄准则(codes of modesty)不会被松懈。于是,这场争论开始涉及到隐私问题。哈马斯尝试降低庭院围墙,试图建立一种监视制度,尽管同上文中提到的以色列的监视策略在意图上有所不同,这同样可以被视为一种使墙透明化的尝试。这场争论终结于由多数的世俗派法塔赫所控制的委员会反对降低围墙,允许重建难民营的纳布卢斯建筑师希达雅·纳芝米(Hidaya Najmi)(自重建以来始终注意不进入营地)继续设计高墙和私人庭院。

因此,第一场争论证明,“通过破坏来设计”的逻辑被扩展到难民营的重建中,城市的布局增加了它的渗透性(permeability)。新的布局能够使以色列国防军未来的武装入侵对财产造成更少破坏。以色列国防军能够以“传统的方式”进入难民营,重型车辆可以在不破坏建筑物的情况下移动,士兵也可以不击碎界墙(party walls)。由于负责建筑的修缮和维护是在敌对状态下进行的,这种设计同毁灭集中营的军事逻辑形成了共谋,这恰恰落入了一个更为明显的陷阱——“人道主义的悖论”——这意味着,在某些条件下,人道主义援助可能最终帮助了压迫者。

如果第一场争论关注的是渗透性问题,第二个关注的则是透明性问题。二者都展示了墙壁的能量,墙壁意味着不同的城市和社会秩序。这些争论反映了以色列人的又一个幻想:巴勒斯坦人的抵抗可以通过破坏和重组其栖息地而被制服。正如斯蒂芬·格拉汉姆(Stephen Graham)所证明的那样,巴勒斯坦城市和难民营常常被以色列国防和政治人物想象成物质垃圾的无形式聚合体——一种易成型的“固态”,以色列国防军士兵可以穿过这种聚合体而挖掘或开凿出自己的道路,用他们的运动重新设计空间。[47]因此,反抗就会被这些“设计”行动所体现出来的那种组织简化所抑制;这种行动的效应可能会带来建筑构造的“现代化”。的确,城市毁灭(urbicide)的历史很大程度上就是由基础设施建设和卫生改进的历史所推动的。基础设施的升级和生活标准的提高试图消除引起不满的条件,但是也会越来越创造出弱点,减弱城镇人口主动反抗的动力。

必须指出的是,同纳布卢斯旧城区不同,上面提到的所有的地方都是难民营。在难民营中,城市毁灭的问题并不是直接发生的。难民营的本质是其暂时性,它表明了要求回归的迫切性。暂时感通常会通过将难民营中的生活条件控制到最低限度而得到维持。在一部分难民营中,污物不受限制地流淌,没有树木,以免难民营被视为永久性的城镇。有时,在难民营中建造一座新房会被视作对于民族事业的背叛,拒绝重建计划的往往是年轻一代。一名居住在德赫伊谢(Daheisha)难民营的年轻巴勒斯坦激进主义者对制片人埃雅尔·希文(Eyal Sivan)说:“他们(联合国)种树,我们(法塔赫激进主义者)就连根拔起”。事实上,一个人在难民营有一处住址,通常意味着其在失去的领土上仍留有一个地址。这本身就能够解释,为什么有12000人在德赫伊谢难民营登记为居民,但那里实际上只有8000人居住。

杰宁难民营的“升级”,以及随之将其整合入杰宁市中,这可能会破坏这种暂时性的地位。事实上,自难民问题产生以来,这已经成为了以色列战略思想中的核心部分。的确,按照汤姆·塞格夫(Tom Segev)近来披露的文件,在1967年战争之后,以色列政府立即讨论了第一个在被占领的西岸地区进行建设的提案,为来自加沙的巴勒斯坦难民建造新的城市。重新安置难民,将他们转变为城镇居民,意味着将“难民问题”的物理上的前提条件加以渗透和破坏。[48]阿里埃勒·沙龙(Ariel Sharon)在1971年作为加沙的军事指挥官,以及在1981年任国防部长时,监督了将加沙难民安排到专门在难民营旁设置的以色列式住宅区居住。在穆罕默德·巴克里(Mohammed Bakri)在2002年4月发生的摧毁之后立即拍摄的电影《杰宁,杰宁》(Jenin Jenin)中,在难民营居民的采访中交流了这样一种印象,只有当破坏与失去居所的威胁再次产生时,难民营才会被接受为一个城市。“难民营毁灭”(campicide),如果存在这样一个词的话,与“城市毁灭”的意义有一定的不同。矛盾的是,它描述的是将难民营建成一个城市,同时失去了其临时“难民营”的地位。正是在这一语境下,我们才能够理解杰宁难民营人民委员会中的一名成员提出的如此的主张,当他看到了新建成的奶油色永久住宅后,他断言:“我们失去了归家的权利”。[49]

6. 狗镇效应

法律和限界依然是…不成文的法律……在边界得以确立的地方,对手不仅被消灭;实际上,他也被赋予了权利,即便胜利者在权力上的优越性是使全面的。而这些(边界),在一个魔力般地模棱两可的方面,是‘平等’的权利:对双方来说,对条约而言,它是同一条不可跨越的界线。——沃尔特·本雅明[50]

墙壁或围栏的系统仅仅是以色列在冲突区域施加“分离的政治”(politics of separation)其中的一个部分。这种政治按照以下原则运作:那就是对于以色列士兵(在一种较小的程度上也是对于移民和以色列公民来说)空间应当是“平滑”、“液态”和“可渗透的”;但它对于巴勒斯坦人来说必须保持“条纹化”和“固态”。除了在西岸建立的墙壁与围栏以外,以色列人还建立了各种各样的临时边界性装置:“壁垒”、“封锁线”、“道路封闭”、“路障”、“检查站”、“隔离区”、“特别安全区”、“军事禁区”、“杀戮地带”。这些都是可传输的、可展开的、可移除的、可变动的“边界装置”(border devices),将巴勒斯坦人能够移动的区域皱折和延展。这些分界线的物质性在场具有各不相同的形式。有时它们几乎完全没有物质存在(例如下达的关闭令)。有的时候,它们区分出了渗透性的不同程度(例如“呼吸式封锁”)。在成为物质性的之前,边界是概念性的和声明性的,有时它们甚至逾越了物质。

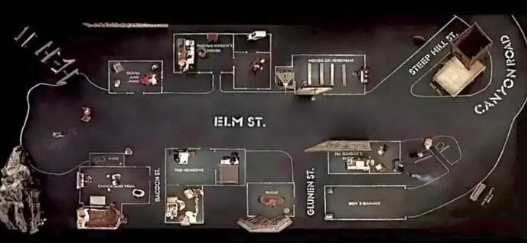

在拉斯·冯·提尔(Lars von Trier)的电影《狗镇》(Dogville)中,房屋之间的边界、内部与外部空间之间的边界都是在室内地板上画出来的,没有物质性的挤压。然而这些标记仍然具有决定角色的运动的能力。而在这里,军事命令,施加这些命令的意愿和手段,也能够在物理上的工事之前创造出壁垒,有时甚至逾越了这些物理事物。另一方面,如果没有法律和军事上的手段来强制执行,最强大的物质性边界都是没有意义的。一座没有法律权威的堡垒就成为了透明的。尽管被占领的加沙和埃及之间的墙壁是最坚固的,在以色列国防军完成重新部署后仅一天,这座墙就被推倒了,因为维持这座墙的政权被取缔了。它曾经伫立着,完全是因为以色列当局愿意用火力和死亡来维持它的存在。

纳维所提出的撤退的前提条件——“只要我仍能越过这道围栏”——意味着一种有条件的撤退,到了紧急情况便可以被取消。事实上,以色列在领土上做出任何让步的前提条件,自奥斯陆协议以来划定的临时边界线,其中都有一项条款,它保证了一个例外的存在,那就是在某些紧急安全情况下——以色列可以自己宣称进入了这种状态——以色列有权“紧追”(hot pursuit)。通过这一权利,以色列就能够强行进入巴勒斯坦控制的地区,进入街区与住房寻找嫌疑人,并将这些嫌疑人带回以色列进行审讯和拘留。这无疑打破了本雅明的引文中所说的墙的对称性质。只要这一允许“紧追”的条款继续被包含在巴以协定制造,以色列就仍然在巴勒斯坦领土上拥有主权——这仅仅是因为,它能够宣布例外状态,使其越过边界,进入巴勒斯坦城市。[51]

7. 非阅读

建筑空间的语词,至少是其名词,似乎就是“室”(rooms),这些范畴以综合或是组合的方式(syncategorematically)被各式各样的空间性动词和副词所叙述和阐发(举例来说,走廊、门道和楼梯),它们又被以涂料、家具、装饰与摆设的形式出现的形容词所加以修饰。——弗雷德里克·詹姆逊[52]

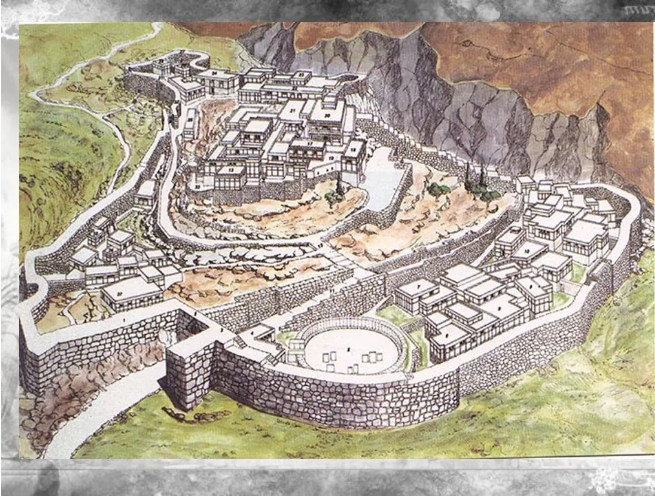

按照汉娜·阿伦特的观点,希腊城市中的政治领域,在字面的意义上,是被两种样式的墙(或是墙一样的法律)所担保的:城市周围的墙,这座墙界定了政治的区域;以及公共区域和私人住房之间的墙,这座墙担保了私人空间的自主性。“前者包围和保卫了政治生活,后者遮挡和庇护了家庭的生物性生命过程。”[53]如果没有这些墙,“就只会有一大片房子,一个集镇(asty),但不会有一座城市、一个政治共同体。”[53]把作为一个政治领域的城市以及乡镇区分开来的东西,是基于维护了公众和私人领域的那些要素所具有的概念上坚固性(conceptual solidity)。在物理上或是概念上毁灭它们,就意味着,城市变成非政治领域,成为没有权利的主体栖息之地。

在历史上的围城战役中,攻破外城墙就标志着主权的毁灭。因此,围城的“艺术”便考察城市外缘的几何形状,以及发展出攻破这样的城墙所需要的同等复杂的技术。在当代的城市行动研究中,如上文所述,越来越关注僭越由住宅围墙(domestic wall)所具现化了的限制所需要的方法。在这方面,我们可以将城市中的围墙视作城墙——律法运作的边缘,民主城市生活的基本条件。正是司法与物理之间的相互作用构成了一座城市,而在这种相互作用中,至关重要的从而就是两个相互关联的政治概念:主权与民主。我们可以将前者理解为“墙壁”(在国家那里则是边界),它被指派去保护后者,而后者又依赖于对私人领域的保护——私人的领域不仅是被定义为房屋的私人内部空间,而且自宗教改革以来,也被定义为良心自由(freedom of conscience)。[54]于是,主权在“城墙”(或边界)的观念中得到了具现化,它界定并保护着(城市)国家的主权边界,而民主则是由界墙的保护所具现化的,它分离并界定了私人空间。对于阿伦特来说,社会的产生就是oikia或家庭的兴起:

即使柏拉图的政治规划预见了对私人财产的取消,并把公共领域扩大到完全消灭私人生活的程度,他也仍然怀着极大的尊敬谈及宙斯·赫启欧斯——边界线的保护者,而且把一个不动产和另一个之间的边界(horoi),称为神圣的,而看不到这和他的主张有任何矛盾。[55]

突破住宅围墙这个物理、视觉和概念上的边界,这标志着“例外状态”最激进的表现形式。在其中,对私人界限的抹消成为了一种核心工具。在这一语境下,我们才能够理解在美国的爱国者法案扩大的所谓“偷窥授权状”(sneak and peek warrants)中,是什么事关重大,这一授权状允许联邦探员秘密进入私人领域,进入嫌疑人的私人空间。[56]住宅围墙的概念化形式就是边界,住所就是敌人的领地,而侵入房产就相当于武装入侵。“国土安全”(现在我们可以将其戏称为“家庭安全”)因而处于民主控制之外。军事分析家们为德勒兹、加塔利、屈米以及其他人所带来的可能性感到欣喜若狂,因为这种内部辖域——颠覆性的私人微观主权(micro-sovereignty of privacy)——现在代表着他们的权力与主权潜在地延伸到了先前所不能及的场所。如此一来,对“家庭”——亲密空间、主体性的空间——的入侵就形成了又一处“最后的边疆”。

穿越墙壁的军事实践将建筑物的物理属性同建筑和社会秩序的句法结合起来。为了使士兵看到墙另一边的活的有机体所开发的技术,以及穿过墙壁的能力,不仅强调了墙壁的物质性,同时也强调了墙的概念本身。一种行动,其运作手段乃是“壁的去壁化”,它不仅破坏了法律秩序和社会秩序,而是也破坏了民主秩序本身。墙壁在物理上和概念上不再坚固,在法律上不再不可穿透,它所创造的功能性空间句法——内部和外部、私人与公共,以及躲避与排除之间的分离——坍塌了。[57]法/壁(law/wall)的回文式语言结构将这两种结构绑缚在一起,使它们相互依存,将建筑等同于法的构造。城市的秩序依托于这样一种幻想:墙壁是稳定的、坚固的、固定不变的。的确,建筑史也倾向于将墙壁视作恒定的或是基础性的——建筑学的不可还原的所予。壁的去壁化必然成为律法的终结。[58]

当科哈维(Kokhavi)声称“空间仅仅一种阐释”,声称他穿梭和跨越城市的建筑构造的运动便对建筑学的要素(墙壁、窗户和门)、因而也对城市本身做出了重新阐释时,他使用理论语言来表明:“赢得”一场城市战争靠的不是破坏城市,而是“重新组织”城市。

如果墙壁仅仅是一堵“墙”的语词,去壁化同样也会成为一种再书写(rewriting)的形式——一种由理论所推动的持续的拆解过程。能够将再书写等同于杀戮吗?也就是说,如果穿墙而过是一种“对空间做出重新阐释”的方式,而城市的性质对于这一阐释的形式来说只是“相对的”,那么“重新阐释”本身足以构成一种凶杀的形式吗?如果说“是的”,那么,将城市“内外颠倒”、重新分配私人和公共空间的“逆向几何学”(inverse geometry),就需要被定义为市区军事行动的一种危害,而这种危害超过了行动在物理上和社会上带来的破坏——因为我们同样需要处理它们的“概念性破坏”。

注释:

This article was originally written for the workshop Urbicide, theKilling of Cities? that Stephen Graham,DanielMonk and David Campbell organized at DurhamUniversityin November 2005. I would like to thankthemfortheirinvitationandcomments.Iwouldalsoliketo thank Brian Holmes and Ryan Bishop for com-menting on earlier drafts, and David Cunningham forworking so hard on making sense of thisone. A versionof this is forthcomingas a chapter in The Politics ofVerticality(Verso2006).

1. My recent workcentres around the way militaries havestartedtothinkaboutcities.ForthisreasonIhavebeen attending military conferences dealing with citiesandurbanwarfareandinterviewingmilitarypersonalinIsrael,theUKandtheUSA. Theinterviewscitedherewereconductedinthecontextof Archilab,TheNaked City, Orleans, 2004, for thecontribution of EyalWeizman, AnselmFranke and Nadav Harel. The ques-tionswere composed by Eyal Weizman and filming wasundertakenbyNadavHarelandZoharKaniel.Inter-viewsconductedinAugustandSeptember2004.

2. ChenKotes-Bar,ʻStarringHimʼ(ʻBekikhuvoʼ),Maʼariv,22 April 2005. Originally in Hebrew; alltranslationsauthorʼsown.

3. Cited in HannanGreenberg, ʻThe Limited Conflict: ThisisHow You Trick Terroristsʼ, YediotAharonot, www.ynet.co.il,23March2004.

4. Cited in ShimonNaveh, ʻBetween the Striated and theSmooth:UrbanEnclavesandFractalManoeuvresʼ,paper delivered at An Archipelago of Exception, confer-ence at the CCCB in Barcelona, 11November 2005, or-ganized by EyalWeizman, Anselm Franke and ThomasKeenan.

5. Amir Oren, ʻThe BigFire Aheadʼ, Haʼaretz, 25 March2004.

6. At least eightyPalestinians were killed in Nablus, mostofthem civilians, between 29 March and 22 April 2002.Four Israeli soldiers were killed. Seewww.amnesty.org;accessed12February2003.

7. Infacttheideaforthemanoeuvreiscreditedtoaplatooncommander and his sergeant in one of the units, bothfrom kibbutz Givaʼat Haiim. See Naveh,ʻBetween theStriatedandtheSmoothʼ.

8. CitedinNaveh,ʻBetweentheStriatedandtheSmoothʼ.

9. Nurhan Abujidi, whoconducted a survey in Nablus afterthebattle, found that 19.6 per cent of buildings affectedbyforcedrouteshadonlyoneopening,16.5percenthadtwo openings, 13.4 per cent had threeopenings, 4.1 percent had fouropenings, 2.1 per cent had five openings,and1.0 per cent(two buildings)had eight openings. SeeNurhan Abujidi, ʻForced to Forget: Cultural Identity andCollective Memory/Urbicide: The Case ofthe Palestin-ian Territories, DuringIsraeli Invasions to Nablus His-toricCenter 2002–2005ʼ, paper presented at Urbicide,the Killing of Cities? workshop at Durham University,November2005.

10. Sune Segal, ʻWhat Lies Beneath: Excerpts from an Inva-sionʼ, November 2002,www.palestinemonitor.org/eye-witness/Westbank/what_lies_beneath_by_sune_segal.htm;accessed9June2005.SeealsoAbujidi,ʻForcedtoForgetʼ.

11. Shimon Naveh, indiscussion after delivering the lectureʻDictaClausewitz: Fractal Manoeuvre, A Brief Historyof Future Warfare in Urban Environmentsʼ, at States ofEmergency: The Geography of Human Rights,a debatethat formed part of Territories Live, Btzalel Gallery, TelAviv, 5 November 2004, organized by EyalWeizmanandAnselmFranke.

12. Simon Marvin, ʻMilitary Urban Research Programmes:Normalising the Remote Control of Citiesʼ,paper deliv-eredatconferenceCitiesasStrategicSites:MilitarisationAnti-globalisation and Warfare, Centrefor SustainableUrbanandRegionalFutures,Manchester,November2002;StephenGraham,ʻFromSanctuariesto“GlassPrisons”? Global South Cities, UrbanWarfare, and USMilitaryTechnoscienceʼ,Antipode(forthcoming).

13. WhentheexhibitionTerritories(curatedbyAnselmFranke and Eyal Weizman)arrived in TelAviv it washosted and paid for bythe Bʼtzalel Academy School ofArchitectureunder the directorship of Zvi Efrat. TheIsraeliMinistry of Education, which indirectly financedthis exhibition, sought to ʻbalance it outʼ by includingNavehinourlistofspeakers.

14. Shimon Naveh, ʻDicta Clausewitzʼ. Compare Navehʼstitles to those used in, among others,Gilles Deleuze andFélix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, Continuum, NewYork and London, 2004; and Gilles Deleuze,Differenceand Repetition, Columbia University Press, New York,1995.

15. SeealsoShimonNaveh,AsymmetricConflict:AnOpera-tional Reflection on Hegemonic Strategies, Eshed GroupforOperationalKnowledge,Tel Aviv,2005,p.9.

16. Telephoneinterview,14October2005.

17. WalterBenjamin,ʻA BerlinChronicleʼ,inOne-WayStreetandOtherWritings,Verso,LondonandNewYork,1979,p.295.

18. SeeGreenberg,ʻTheLimitedConflictʼ.

19. See Eric Bonabeau,Marco Dorigo, and Guy Theraulaz,Swarm Intelligence: From Natural toArtificial Systems,OxfordUniversity Press, Oxford, 1999; Sean J.A. Ed-wards, Swarming on the Battlefield:Past, Present andFuture, RAND,Santa Monica CA, 2000; John ArquillaandDavid Ronfeldt, eds, Networks and Netwars:TheFuture of Terror, Crime, andMilitancy, RAND, SantaMonicaCA,2001.

20. Naveh,ʻBetweentheStriatedandtheSmoothʼ.

21. CarlvonClausewitz,OnWar,EverymanʼsLibrary,Lon-don,1993, pp. 119–21; Manuel De Landa, War intheAge of Intelligent Machines,Zone Books, New York,1991,pp.78–9.

22. Michel Foucaultʼsdescription of theory as a ʻtool-boxʼwasoriginallydevelopedinconjunctionwithDeleuzein a 1972 discussion. See Gilles Deleuzeand MichelFoucault, ʻIntellectualsand Powerʼ, in Michel Foucault,Language, Counter-Memory, Practice,Cornell Univer-sityPress,Ithaca,1980,p.206.

23. See Arquilla andRonfeldt, eds, Networks and Netwars.See also Shimon Naveh, In Pursuit of Military Excel-lence:TheEvolutionofOperationalTheory,FrankCass,PortlandCA,1997.

24. SeeDeLanda,WarintheAgeofIntelligentMachines.

25. Col.EricM.Walters,ʻStalingrad,1942:WithWill,Weapon, and a Watchʼ, in Col. John Antaland Maj.BradleyGericke,eds,CityFights,BallantineBooks,NewYork,2003,p.59.

26. SeeB.H.LiddellHart,Strategy,PlumBooks,NewYork,1991.

27. SharonRotbard,WhiteCity,BlackCity,BabelPress,TelAviv,2005,p.178.

28. Marshal Thomas Bugeaud, LaGuerre des rues et desmaisons,J.-P. Rocher, Paris, 1997. The manuscript waswritten in 1849 in Bugeaudʼs estate in the Dordogneafter his failure quickly to suppress theevents of 1848.Bugeauddidnotmanagetofindapublisherforhisbook,butdistributed a small edition among his colleagues. Inthe text Bugeaud suggested widening the Parisian roadsand removing corner buildings at strategiccrossroads inordertoallowforawiderfieldofvision.Theseandothersuggestions were implemented by Haussmann severalyearslater.SeeRotbard,WhiteCity,BlackCity.

29. Auguste Blanqui, Instructionspour une Prise dʼArmes,Sociétéencyclopédiquefrançaise,Paris,1972. Avail-able online atwww.marxists.org/francais/blanqui/1866/instructions.htm.

30. InterviewwithGilFishbein,TelAviv,4September2002.Fishbein describesthe first stages of the battle of Jeninbeforethebulldozerswerecalledin.

31. CitedinYagilHenkin,ʻTheBestWayintoBaghdadʼ,

NewYorkTimes,3 April2003.

32. NavehmentionedthathecurrentlyworkswiththeHebrew translation of Bernard Tschumiʼs ArchitectureandDisjunction.OriginallyBernardTschumi,Archi-tectureandDisjunction,MIT Press,CambridgeMA,1997.

33. ʻGoinside,heorderedinhystericalbrokenEnglish.Inside! I am already inside! It took me afew seconds tounderstand that thisyoung soldier was redefining insidetomeananythingthatisnotvisible,tohimatleast.My

being “outside”within the “inside” was bothering him.Notonly is he imposing a curfew on me, he is alsoredefiningwhatisoutsideandwhatisinsidewithinmyownprivatesphere.ʼ CitedinSegal,ʻWhatLiesBeneathʼ.

34. GeorgesBataille,ʻArchitectureʼ,inEncyclopaediaAcephalica. Available online at:http://website.lineone-net/~d.a.perkins/pGBARCHI.html.

35. Brian Hatton, ʻTheProblem of Our Wallsʼ, Journal ofArchitecture 4, Spring 1999, p. 71.Krzysztof Wodiczko,ʻPublicAddressʼ,WalkerArtCentre,Minneapolis,1991,published inconjunction with an exhibition held at theWalkerArtCenter,Minneapolis,11October1992–3January1993,andtheContemporaryArtsMuseum,Houston,22May–22August1993.

36. Zuri Dar and Oded Hermoni, ʻIsraeli Start-Up Devel-ops Technology to See through Wallsʼ, Haʼaretz, 1 July2004; Amnon Brazilay, ʻThis Time They Do Not to Pre-pare to the Last Warʼ, Haʼaretz, 17 April 2004. See alsoAmir Golan, ʻThe Components of the Abilityto Fight inUrbanAreasʼ,Maʼarachot384,July2002,p.97.

37. SeeGreenberg,ʻTheLimitedConflictʼ.

38. FromSeptember2000tothetimeofitsevacuation,1,719 Palestinians were killed in Gaza – two-thirds ofthem unarmed and uninvolved in anystruggle; 379 ofthem children. SeeAmira Has, ʻThe other 99.5 percentʼ,Haʼaretz,24August2005.

39. This resonates withNavehʼs attitude to American mili-taryaction in Falluja: ʻa disgusting operation,they flat-tened the entire city… ifwe would have done just thatwewouldhavesavedourselvesmanycasualtiesʼ.

40. Some 1,500 otherbuildings were damaged and 4,000peoplewere left homeless. Fifty-two Palestinians werekilled, more then half of them civilians. Some, includ-ing those who – elderly or disabled –couldnʼt leave ontime, were buriedalive under the rubble of their homes.SeeAmnesty International, Shielded fromScrutiny: IDFViolations in Jeninand Nablus, 4 November 2002; andStephenGraham,ʻConstructingUrbicidebyBulldozerin the Occupied Territoriesʼ, in Cities, War and Terror-ism,Blackwell,Oxford,2004.

41. A further $5 million from Saddam Hussein was dividedbetween the families whose homes weredestroyed, andthosewholostrelatives.

42. Between 10 and 15 per cent of the original ground areaof the lots of destroyed buildings werelater registered aspublic ground.In some cases, this area was seized onlyonthe ground floor. UNRWA bought further land on theedge of the camp and relocated some of the householdsfrom the destroyed core. The project wasdedicated toSheikh Zayed Bin SultanAl Nahyan, the late presidentoftheUAE.

43. A popular committee is an organizational form based onparticipatory democracy developed withinthe occupiedvillages, refugee campsand cities which emerged duringthefirstintifada.Inmostplaces,politicalpartiesfromthemain factions in the PLO, as well as Hamas andIslamicJihad,appointedrepresentatives.

44. Gideon Levy, ʻTank Lanes Built between New JeninHomesʼ, Haʼaretz, 10 May 2004. This was engaged inthe exhibition Walking through Walls, curated by EyalWeizman,AnselmFrankeandNadavHarel.

45. The first project director, the British Iain Hook, waskilled by IDF soldiers, who later claimedto have mis-takenhimforanarmedPalestinian.

46. ʻWegotblamedfordoingitthiswaybutwemadethe

roads wider for carsand ambulances – it would be sillynotto.Wejustwantedtomakeanormallivingarea

…weseeitfromatechnicalaspect,notintermsofwar;theIsraeliswillcomeinregardless.ʼSeeJustinMcGuirk, ʻJeninʼ, IconMagazine 24, June 2005, www.icon-magazine.co.uk/issues/024/jenin_text.htm. See alsoLevy,ʻTankLanesʼ.

47. SeeGraham,ʻConstructingUrbicideʼ.

48. Tom Segev, Israel in 1967, Keter Books, Jerusalem,2005,p.566(inHebrew).

49. But this is nottypical of the position of many otherrefugeesdelighted by their new homes. See Levy, ʻTankLanesʼ.

50. Walter Benjamin,ʻCritique of Violenceʼ, in Reflections,Schocken Books and Random House, NewYork, 1989,pp.295–6.

51. In recent months, thepractice has been reported in theareasaround Ramallah. Prime Minister Netanyahu pre-viouslystated:ʻHotpursuitisasub-issue.Itʼsaspe-cificinstanceofagenericissue,andthegenericissueis the freedom ofaction of Israel to protect its citizenswherevertheyare.Andagainstwhateverthreatsemanatefrom anywhere.ʼ Press conference withPrime MinisterNetanyahuontheHebron Accord,13January1997;availableonlineatmfa.gov.il.

52. Fredric Jameson, ʻIsSpace Political?ʼ, in Neil Leach,ed.,Rethinking Architecture: A Reader inCultural The-ory,Routledge,LondonandNewYork,1997,p.261.

53. Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, Chicago Uni-versityPress,Chicago,1998,pp.63–4.

54. Becausewallsfunctionnotonlyasphysicalbarriersbut as devices of information exclusion(of vision andsound), they have provided, since theeighteenth cen-tury, according toarchitectural historian Robin Evans,thephysical infrastructure for the construction of pri-vacy and modern subjectivity. See Robin Evans, ʻTheRightsofRetreatandtheRightsofExclusionʼ,inTranslation from Drawing to Building andOther Es-says, ArchitecturalAssociationPublications,London,1997.

55. This is developed inPlatoʼs Laws, Book 8, 843; cited inArendt,TheHumanCondition,p.30.

56. The Fourth Amendmentof the US Constitution guar-anteesindividualsʼ rightsagainstunreasonablesearchandseizure.Itisrequiredthatthegovernmentgivesnoticebefore searching through or seizing an individu-alʼs belongings. Before the USA Patriot Act was passedin Congress on 24 October 2001, priornotice could besuspended only undera narrow set of circumstances.Section213 of the Act expanded so-called ʻsneak andpeekʼ warrants. Under this section the government candelay notice of a search if it can showʻreasonable causeto believe thatproviding immediate notification of theexecutionof the warrant may have an adverse resultʼ.Thismeans that government agents can enter a dwell-ing without notice if they have a reasonable suspicionthatanannouncementwouldinhibittheinvestigationof a crime, by, for example, enablingthe destruction ofevidence. Thisprocedure replaced the old standard ofʻknockand announceʼ by which, when executing a war-rant, law enforcement officials must generally announcetheirpresence.www.humanrightsfirst.org/us_law/loss/loss_ch2.htm.

57. Evans, ʻThe Rights ofRetreat and the Rights of Exclu-sionʼ,p.38.

58. Hatton,ʻTheProblemofOurWallsʼ,pp.66–7.