Part 1: Solipsism, Stigmata, and Silencing Invocations

The photographs I choose have an argumentative value. They are the ones I use in my text to make certain points.

—Roland Barthes in conversation with Guy Mandery1Typically, there is in this grammar of description the perspective of “declension,” not of simultaneity, and its point of initiation is solipsistic.

—Hortense Spillers2The privation of History protects and tames the colonizer’s imagination as viewer.

—Chéla Sandoval3

1.

I’ve thought for quite some time that Roland Barthes’s grief at the recent death of his mother was the sole and logical reason for his withdrawing from us the image of his dearly departed mother as a young girl in the famous Winter Garden Photograph, of which he writes at length in Camera Lucida. It is an image whose presence (and absence) in the book plainly has a transformative effect on his thinking with and about photography, but the vagaries of grief are unpredictable, and photographs can indeed wound. Having attributed its absence to grief, and thus having neglected the fraught politics of visibility on which Barthes’s theory is premised, it is only recently, and in the light of the instructive interventions of Kaja Silverman, Fred Moten, Tina Campt, and Jonathan Beller, that I have thoroughly reconstructed my point of view. 4 On reflection, Barthes’s retention of that (iconic?) image seems entirely consonant with the anti-historical, and thus antisocial, logic of the theory of photography that he develops.5

This is to say that if, as Barthes’s theory suggests, a photograph is valuable only to the extent that it catalyzes and animates a set of private memories and ahistorical interpretations, all of which might then stand in place of the image that triggers them, then why share photographs at all? In contemplating Camera Lucida now, in the wake of the fortieth anniversary of its publication, I am moved to ask: How could a book so intensely bound up with photography and loss show so little generosity, and why, today, should we heed its call? Beyond this, what might insights from black studies bring to bear on a book so indebted to the identification and rejection of difference in the expropriative formulation of Barthes’s inner self?

If this reaction seems extreme, we should recall how Barthes first describes “the punctum”: it is that thing that advenes, the “accident which pricks me,” the “sting, speck, cut, little hole,” the “detail” whose “mere presence changes my reading” so “that I am looking at a new photograph, marked in my eyes with a higher value.”6 The punctum is a mutually self-constituting thing, since Barthes tells us that “it animates me, and I animate it” (20). Moreover it issues from Barthes himself: “Whether or not it is triggered, it is an addition: it is what I add to the photograph and what is nonetheless already there” (49). It produces in him an excitation, and this detail has “a power of expansion. This power is often metonymic” (45). In fact the punctum unleashes desire beyond material restriction: it “is a kind of subtle beyond—as if the image launched desire beyond what it permits us to see” (59).

The punctum empowers a free-ranging and unregulated desire, one which can alight in and overwhelm any image in which it is instantiated. It moves according to the vicissitudes of a law utterly untethered from the specific contours of material and social history: it is free and imperious travel. In Camera Lucida, the radical proposition of the there-ness of a person in the past is ultimately a pretext for various acts of colonization of the depicted by Barthes’s own cherished and subjective memories.

As he writes, “I have no need to question my feelings in order to list the various reasons to be interested in a photograph.” For Barthes, what counts above all is affective feeling—and an attention and intention driven by the irreducible strength of subjective feeling. Thus, he is concerned to understand “if another photograph interests me powerfully … what there is in it that sets me off.” Accordingly, what matters is “the attraction certain photographs exerted upon me,” and it is that attraction which “allows me to make Photography exist.” Without it, “no photograph.” (19)

This whimsically subjective and ahistorical mode of attending to the photograph, and of determining its value, serves as a pretext for Barthes’s expropriative formulation and extension of an inner self. Such a method eerily emboldens and ratifies the supremacist logics Barthes earlier critiqued in his 1957 Mythologies.7 The postcolonial feminist theorist Chéla Sandoval defines that book as posing “the question of how ‘innocent’ or well-intentioned citizens can enact the forms-of-being tied to racist colonialism,” and thus to cultural logics driven by “a colonizing consciousness incapable of conceiving how real differences in others can actually exist, for everything can be seen only as the self—but in other guises.”8 As Sandoval writes, in Mythologies Barthes set out with the hope that semiology might challenge supremacism “in all its modes” through a critical method

that operates through (1) the recognition of differences and their inescapable consequences; (2) the reconnection of history to objects; (3) the disavowal of pure identification; (4) the self-conscious relocation of the practitioner of semiology in transits of meaning and power; (5) the undermining of authority, objectivity, fact, and science insofar as it seeks to reconnect each of these processes to the history, power, and systems of meaning that create them; and (6) the constant reconstruction of the consciousness of the semiotic practitioner, along with the method itself, as both mutually interact to call up something else.9

And yet, at the very outset of Camera Lucida, Barthes willfully rejects “an importunate voice (the voice of knowledge, of scientia)” which reprimands him for an excessive interest in the “amateur” field of family photography, whose dynamics can allegedly be elucidated by sociologists (7). “Yet I persisted,” he declares, since “another, louder voice urged me to dismiss such sociological commentary; looking at certain photographs, I wanted to be a primitive, without culture” (7). Barthes resolves instead to theorize only from “a few photographs, the ones I was sure existed for me,” and thus, he decides imperiously “to take myself as mediator for all Photography” (8).

Barthes’s theoretical work begins in the comfortable solipsism of white male universality, in his notional suspension from socially and historically constituted knowledge, in some imagined “primitive” state outside of culture and history. The ethical basis of Camera Lucida is given in Barthes’s explicit resolution, at the outset of the book, to try to make “what Nietzsche called ‘the ego’s ancient sovereignty’ into a heuristic principle” (8). One has to ask: If photographs exist on the basis of the strength of individual feeling alone, then why share something as specifically precious as an image of one’s dead mother as a child? Put another way: the reason for Barthes’s withdrawal of the Winter Garden Photograph is given in the willful solipsism of his method, and thus it is that method which is at issue in any evaluation of the work.

I think this means that for me, the Winter Garden Photograph—its looming, absent presence in Camera Lucida—instigates a set of urgent and complex questions about photography and sociality, about seeing and sharing, about touching and being touched, about death and love, about whiteness and its supremacy, about presence and erasure—which must be worked through in relation to the determining factors of race, class, gender, and ableism, all of which constitute the disavowed bases on which Barthes develops his theory of photography. I am interested in Barthes’s retention of the Winter Garden Photograph as a rejection of the photograph’s umbilical linkage with its viewer. I am interested in that retention as a refusal of the vital force of that light which, according to Barthes, acts as a “carnal medium” (81), as an extensible skin that collapses the very divisions he so effortlessly resurrects throughout his text.

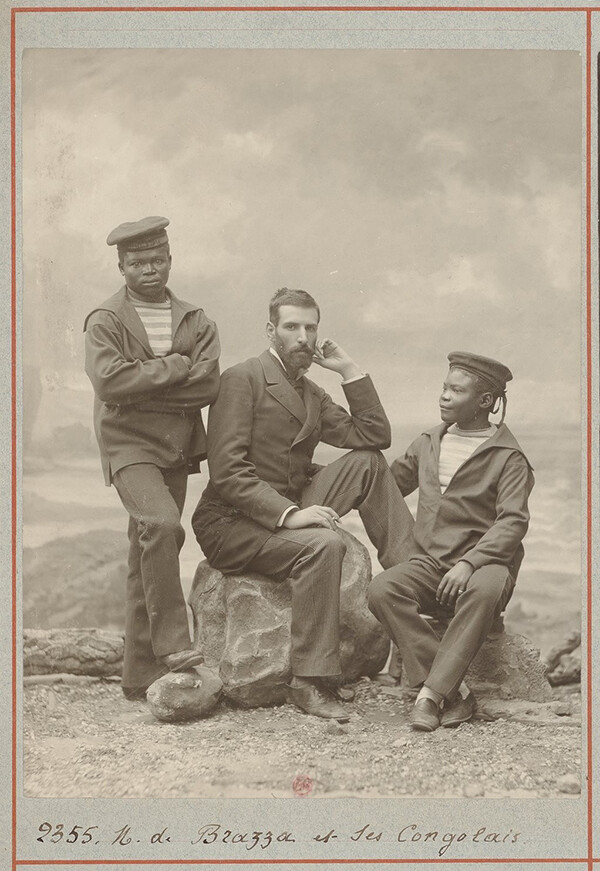

Felix Nadar, Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza et ses Congolais (“Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza with his Congolese”), 1882.

2.

The body is the sign of a difference that exceeds the body.

—Samira Kawash, Dislocating the Color Line10

Barthes’s theory of photography in Camera Lucida is founded on his identification of the “studium” and the punctum, which together unchain a series of impassioned and far-reaching claims about photography’s ontology. These two distinct but interacting elements emerge in the first part of the book, in which Barthes has been noting, phenomenologically, that some few images “provoked tiny jubilations, as if they referred to a stilled center, an erotic or lacerating value buried in myself … and that others, on the contrary, were so indifferent to me that by dint of seeing them multiply, like some weed, I felt a kind of aversion toward them, even of irritation” (16). He resolves “to extend this individuality to a science of the subject”—to form a theory of the photograph according to the caprices of his “overready subjectivity,” because “of this attraction, at least, I was certain” (18). Barthes decides

to compromise with a power, affect; affect was what I didn’t want to reduce; being irreducible, it was thereby what I wanted, what I ought to reduce the Photograph to; the anticipated essence of the Photograph could not, in my mind, be separated from the “pathos” of which, from the first glance, it consists … As Spectator I was interested in Photography only for “sentimental” reasons; I wanted to explore it not as a question (a theme) but as a wound: I see, I feel, hence I notice, I observe, and I think. (20–21)

Barthes’s affective method models a relationship to photography that is thus limited, in its capacity to respond to photographs, by the depth and breadth of one’s instinctual, preconscious affective relationships to images: it is restricted to the vagaries of gut instinct. On this basis Barthes responds with utter disinterest to a photograph by Koen Wessing, taken in Nicaragua in 1979 during the revolution that sought to overthrow the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza García:

Did this photograph please me? Interest me? Intrigue me? Not even. Simply, it existed (for me). I understood at once that its existence (its “adventure”) derived from the co-presence of two discontinuous elements, heterogeneous in that they did not belong to the same world … the soldiers and the nuns. (23)11

Barthes’s lack of interest in Wessing’s photograph impels him to “to try to name … these two elements whose co-presence established, it seemed, the particular interest I took in these photographs. The first, obviously, is an extent, it has the extension of a field, which I perceive quite familiarly as a consequence of my knowledge, my culture” (25). This is the studium, which “doesn’t mean … ‘study,’ but application to a thing, a kind of general enthusiastic commitment … but without special acuity” (26). Wessing’s photograph conforms to this generality, to what Barthes describes as “a classical body of information: rebellion, Nicaragua, and all the signs of both: wretched un-uniformed soldiers, ruined streets, corpses, grief, the sun, and the heavy-lidded Indian eyes … in these photographs I can, of course, take a kind of general interest,” Barthes continues, “ … but in regard to them my emotion requires the rational intermediary of an ethical and political culture” (26). Thus, faced with Wessing’s photograph: no affect, no “fulgurating” force.

Together with this studium, but defined in substantive contrast to it, Barthes describes the punctum as an element that “will break (or punctuate) the studium. This time it is not I who will seek it out … it is this element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me” (26). It is “this wound, this prick, this mark made by a pointed instrument” (26–27). This first definition of the punctum resolves in the figure of a detail in the photograph that expands metonymically and uncontrollably to subsume and transform the whole: “Occasionally (but alas all too rarely) a ‘detail’ attracts me. I feel that its mere presence changes my reading, that I am looking at a new photograph, marked in my eyes with a higher value. This ‘detail’ is the punctum” (42).

In the series of photographs on which Barthes subsequently alights in his elaboration of this first definition of the punctum, certain details rise up out of the scene, animating him as he reciprocally animates the photograph. Each one of these are alike in their tendency to underscore disproportions or deviations in other people (whether of physique, or of proper comportment according to the strictures of race, gender, and class), or they are defined by their incidental capacity to unleash elements of Barthes’s personal history over and against the indexical specifics of the scene. If theorist and art historian Kaja Silverman is correct in writing that the look which Barthes “brings to bear” in Camera Lucida “is a wayward or eccentric look, one not easily stabilized or assigned to preexisting loci,” it is nevertheless unerringly consistent in its condescension and indifference, enamored only of its own memory.12

Thus, in James Van der Zee’s 1926 studio portrait of three African Americans, Barthes alights on the punctum of the low slung belt of “the ‘solacing Mammy’… whose arms are crossed behind her back like a schoolgirl,” before then fixating on the punctum of her “strapped pumps,” describing their sartorial choices as “an effort touching by reason of its naïveté” (43). In William Klein’s 1954 portrait of a group of small children, Barthes writes that “what I stubbornly see is the one child’s bad teeth” (45). In André Kertész’s 1921 portrait of a blind violinist flanked by two small children, Barthes’s writes that “I recognize, with my whole body, the straggling villages I passed through on my long-ago travels in Hungary and Rumania” (45). In Duane Michals’s 1958 portrait of Andy Warhol, in which Warhol hides his face beneath his upstretched hands, “the punctum is not the gesture but the slightly repellent substance of those spatulate nails, at once soft and hard-edged” (45).

In Lewis Hine’s 1924 photograph, captioned “Idiot children in an Institution. New Jersey, 1924,” Barthes writes that he “hardly see[s] the monstrous heads and pathetic profiles (which belong to the studium); what I see … is the off-center detail, the little boy’s huge Danton collar, the girl’s finger bandage” (51). In Nadar’s 1882 portrait of Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza sat between his two unnamed black boys “dressed as sailors,” Barthes sees the confidently crossed arms of one boy stood above de Brazza as the punctum, and notes the other boy’s hand, perched on de Brazza’s thigh, “as ‘aberrant’” (51). After a period of reflection on Van der Zee’s portrait—once “this photograph has worked within me”—Barthes writes that

I realized that the real punctum was the necklace she was wearing; for (no doubt) it was this same necklace (a slender ribbon of braided gold) which I had seen worn by someone in my own family, and which, once she died, remained shut up in a family box of old jewelry (this sister of my father never married, lived with her mother as an old maid, and I had always been saddened whenever I thought of her dreary life). (53)

Barthes continues: “On account of her necklace, the black woman in her Sunday best has had, for me, a whole life external to the portrait” (57). This would imply that were she not in possession of a necklace that resembled his aunt’s,13 she would have had no life for him before or beyond the portrait. Early in Camera Lucida it becomes apparent that Barthes’s method is hinged upon what Fred Moten has brilliantly described as a “silencing invocation,” which is unrepentantly violent.14 The imperious air of dismissal of the actual and possible lives of Others in Barthes’s text makes plain that photographs, and the people appearing in them, serve him as palanquins on what Moten dubs “the europhallic journey to the interior.”15

Thus, as with the earth in Kertész’s rural portrait from Hungary, so too with the “American blacks” (43) in the Van der Zee portrait: those who Barthes cites as marked by the presence of the punctum either serve as the tabula rasa onto which he might reinscribe his own history, or they are united in a chorus of failed attempts to conform to hegemonic standards of normalcy which position the bodies depicted in those images as different, as poor, as aberrant, as black. If Barthes wishes to claim that “it is not possible to posit a rule of connection between the studium and the punctum (when it happens to be there)” (42), it is nevertheless alarming to note the tremendous consistency with which the punctum’s presence marks deviation and degeneracy from a set of corporeal, classed, gendered and raced norms throughout his book. It seems that precisely at the point of his discovery and elaboration of the punctum, in the midst of his “primitive” solipsistic rejection of history, knowledge, and culture, Barthes is nevertheless enmeshed in the violently hierarchical logics of whiteness. He most certainly is not outside of culture, however forceful his desire.16

What is more, all of this occurs within a series of images that he steadfastly refuses to clearly see. The hierarchical dynamic between the studium and the punctum seems to function in such a way that the scene itself (the studium), in which he is “sympathetically interested, as a docile cultural subject” (43), relays little of substance or import or attraction about the people that it depicts, since it is one among the “thousands of photographs” (26) of which Barthes writes that “I felt a kind of aversion to them, even of irritation” (16). Aversion is “the action of turning away … one’s eyes,” it is “the action of … warding off, getting rid of.”17 I would argue that it is precisely because Barthes hardly sees anything other than his punctum (his prick) that his text is capable of effecting such an unbroken series of acts of erasure and displacement of human subjectivity.

When he is himself the object of the camera’s attentions, Barthes experiences terror— “what I see is that I have become Total-Image, which is to say, Death in person; others—the Other—do not dispossess me of myself, they turn me ferociously into an object, they put me at their mercy”—and he thus declaims, in his own defense, that “It is my political right to be a subject which I must protect” (15). No such consideration informs his response to the portraits of poor children, institutionalized and differently abled children, black families, survivors of slavery or the servant boys of French colonial governor Savorgnan de Brazza. Rather, what he effortlessly produces in his first formulation of the punctum is a work that perpetrates what Gayatri Spivak has called “epistemic violence,” achieved through “the asymmetrical obliteration of the trace of that Other in its precarious Subject-ivity.”18

3.

Skin re-members, both literally in its material surface and metaphorically in resignifying on this surface, not only race, sex and age, but the quite detailed specificities of life histories.

—Jay Prosser, Skin Memories19

In the second half of Camera Lucida, having determined at the close of the first that “my pleasure was an imperfect mediator,” Barthes resolves to “descend deeper into myself to find evidence of Photography” (60). In this section, his second and final form of the punctum is unveiled. Motivated by his deep grief at the death of his mother, Barthes had resolved “one November evening” to go through some photographs with “no hope of ‘finding’ her” (63). In this fervent struggle to retrieve the dead and return her to the present, through the offices of photographs that imperfectly deliver to Barthes only fragments that miss her essence, he describes himself as confronted by “the same effort, the same Sisyphean labor: to reascend, straining toward essence, to climb back down without having seen it, and to begin all over again” (63). In the throes of this mad labor he stumbles across the Winter Garden Photograph, its corners “blunted from having been pasted into an album, the sepia print … faded … The picture just managed to show two children standing together at the end of a little wooden bridge in a glassed-in conservatory, what was called a Winter Garden in those days” (67).

In this photograph, or more properly through it, Barthes “rediscover[s]” his mother (69). It retrieves for him the “distinctness of her face, the naïve attitude of her hands,” but more than this it indexes specific and true traits of her personality “so abstract in relation to an image,” which are “nonetheless present in the face revealed in the photograph” (69). For Barthes, the Winter Garden Photograph “collected all the possible predicates from which mother’s being was constituted” (70), and thus it effected for him the necessary transcendence of death’s impassable limits, and the revivification of “the desired object, the beloved body” (7), although this reversal comes at a cost: “I arrived, traversing three-quarters of a century, at the image of a child: I stare intensely at the Sovereign Good of childhood, of the mother, of the mother-as-child. Of course I was then losing her twice over, in her final fatigue and in her first photograph, for me the last” (71).

Returning to himself in his complex of grief and joy, Barthes discovers that “something like an essence of the Photograph floated in this picture,” and in keeping with his solipsism, “I therefore decided to ‘derive’ all Photography (its ‘nature’) from the only photograph which assuredly existed for me” (73). By way of the effects of this photograph, Barthes comes to understand that his “interrogation of the evidence of photography” must not be motivated by “pleasure, but in relation to what we romantically call love and death” (73).

It is thus as a function of the Winter Garden Photograph that he “rediscovers the truth of the image,” and determines that

in Photography I can never deny that the thing has been there. There is a superposition here: of reality and of the past. And since this constraint exists only for Photography, we must consider it, by reduction, as the very essence, the noeme of Photography … The name of Photography’s noeme will therefore be: “That-has-been.” (76–77)

This is the second and final form of the punctum, unveiled in his realization that photography possesses an “evidential force, and that its testimony bears not on the object but on time” (89).

This secondary conception of the punctum constitutes an ontological definition. The mark of that-has-been is indexical, and thus bears a physical relationship to time, and to all photographs. Yet Barthes claims that it may nevertheless be “experienced with indifference, as a feature which goes without saying” (77). He continues: “It is this indifference which the Winter Garden Photograph had just roused me from” (77). We are thus faced with a punctum that is universal, that is of the order of an intensity bearing on time and materiality, but that might nevertheless be “experienced with indifference,” and that is in this sense a varying factor of spectatorial experience, but a constant of photography’s ontology.

In the very discovery and elaboration of a punctum that constitutes a new universality, a punctum which certifies that “what I see has been here, in this place which extends between infinity and the subject (operator or spectator); it has been here, and yet immediately separated; it has been absolutely, irrefutably present, and yet already deferred” (59), Barthes retreats into privation from others. He distances himself from the notion of being for any other except his mother, and theorizes photography as structured by a punctum that need not wound—an arrow that pierces nothing, since for us, the indexical fact of the existence of others, materially transported to us in photographs, constitutes “nothing but an indifferent picture, one of the thousand manifestations of the ‘ordinary’” (73). Fred Moten responds to this withdrawal of temporal indexicality in his extraordinary essay “Black Mo’nin’,” writing that “in other words, historical particularity becomes … egocentric particularity … Barthes is interested in, but, by implication, does not love the world.”20 In effect, Barthes’s second theorization and valorization of the punctum declares: the mad, extraordinary historical fact of the existence of others will likely only matter if you love them as I love my mother.

At this juncture, Barthes returns to a portrait by Richard Avedon of William Casby, which he has reproduced and discussed earlier in the book:

I think again of the portrait of William Casby, “born a slave,” photographed by Avedon.21 The noeme here is intense; for the man I see here has been a slave: he certifies this not by historical testimony but by a new, somehow experiential order of proof, although it is the past which is in question—a proof no longer merely induced: the proof-according-to-St.-Thomas-seeking-to-touch-the-resurrected-Christ. (79–80)

We see here that a simple portrait of William Casby materializes the brute fact, the vast articulated edifice and history of slavery, so that the two are coextensive and inseparable. Casby is the godhead of Barthes’s theory of the ontology of the photograph (as something that gives truth and reality without mediation), and the touch of the image, which is here equivalent to the touching of his flesh, provides the definitive proof that eradicates our/St. Thomas’s doubt in the face of this resurrection. It is also precisely at this juncture that Casby disappears from Barthes’s text. In his place:

I remember keeping for a long time a photograph I had cut out of a magazine—lost subsequently, like everything too carefully put away—which showed a slave market: the slavemaster, in a hat, standing; the slaves, in loincloths, sitting. I repeat: a photograph, not a drawing or engraving; for my horror and my fascination as a child came from this: that there was a certainty that such a thing had existed: not a question of exactitude, but of reality: the historian was no longer the mediator, slavery was given without mediation, the fact was established without method. (80)

All traces of supporting texts, all suggestions of a prior caption, all recollections of contextual indicators in the magazine that might have vouchsafed that what was displayed in the image was true have been elided from his account. The that-has-been of slavery supersedes even the photographic processes that mediate evidence of historical facts. This epidermal indexing of slavery—what the Apostle Thomas calls “the print of the nails” in the flesh of Christ22—recurs in Barthes’s earlier writing on Casby’s face, and has an exclamatory force that resembles the definition of the index elaborated by Charles Sanders Peirce, and expanded by Brian Massumi. For Peirce, indexes “act on the nerves of the person and force his attention.”23 Massumi continues, in dialogue with Peirce, writing that indexes are

nervously compelling because they “show something about things, on account of their being physically connected to them” in the way smoke is connected to fire. Yet they “assert nothing.” Rather, they are in the mood of the “imperative, or exclamatory, as ‘See there!’ or ‘Look out!’ The instant they “show” we are startled: they are immediately performative.24

In Barthes’s recollection of the slavemaster photograph, in his encounter with Avedon’s portrait of Casby, we see the instantaneity of a corporeal response to a visual sign that exclaims “slavery!” and in so doing, provokes horror. In his essay, Massumi will go on to elaborate the ways that such affective responses as Barthes’s horror can legitimate violent actions in the present against notionally probable “future threats” within the logic of the War on Terror. For our purposes, the evaporation of all mediation from Barthes’s account of this horribly fascinating encounter is of vital significance, because it transposes to the black body something that properly resides within the mind of a white child.

I dwell on this elision of the constitutive mediations that enunciate “slavery!” for Barthes because it suggests, troublingly, that at the core of his thinking in Camera Lucida there is an unquestioned assumption that racial subjugation irreducibly inheres in the flesh of the Other, and is not in fact entangled with and produced through processes of mediation. Barthes’s disproportionate interest in the face of William Casby, and his relative indifference to imagery of the practices of enslavement that feature white men (the slavemaster photograph, Nadar’s portrait of de Brazza) suggests an inability to contend with the violent depredations of racism when the proponents and beneficiaries of such violence also figure within the frame. In this sense, slavery is less a field of broken relations between people than an ontological condition that inheres—magically and ahistorically—in Casby’s flesh. If blackness speaks slavery into being performatively, then blackness is deictic: capable of direct proof of abjection, tending to directly show degeneracy and subjugation without intermediary, and thus by virtue of its essence.

We might pause for a moment here to consider the following urgent questions: How exactly might “slavery” be laid bare, following Barthes, in the photographic depiction of the face of a former slave? How might the general historical condition of slavery, and the fundamentally inassimilable experience of its perpetration—which by definition is imposed with lethal and indiscriminate force by slavers upon their victims—inhere in the aspect of the formerly enslaved? By what tool, with what force is Casby’s skin inscribed with slavery? Where might we locate the evidential mark? Isn’t enslavement—the brutal, decimating, expropriative, rapacious and lustfully violent practice of subjection—essentially defined by the actions of slavers? What does it mean to see the essence of American slavery in the visage of a black man, William Casby, who is then swiftly objectified into evidence of white supremacist violence, dis-individuated and hyper-enlarged to stand metonymically for the entire system of judicial and extrajudicial apartheid of which he was not the cause, nor the architect, nor the executor, but the victim and survivor?

Portrait of Napoléon Bonaparte (Jérôme) by Atelier Nadar, date unknown.

4.

If such a counter reading of Camera Lucida turns out to be correct, then the “essence of photography,” precisely defined by Barthes as “that has been,”—and acted upon in similar ways by entire populations—has for many decades meant the practical disavowal of racism by its beneficiaries.

—Jonathan Beller25

If throughout Camera Lucida Barthes regularly averts his gaze, we might think this gesture in the context of a disavowal, and consider the mirroring relationship between the lost slave market photograph, depicting “the slavemaster, in a hat, standing, the slaves, in loincloths, sitting” (80), and Nadar’s portrait of Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, which Barthes reproduces in the book. Savorgnan de Brazza was a French colonial explorer who participated in the French suppression of the “Mokrani Revolt” in Algeria in 1871 (known locally as “the French War”) in which nearly one third of the population rose up in arms against French colonial rule. Savorgnan de Brazza “founded” the colony Brazzaville—in the contemporary Republic of Congo—and, from 1882 (the year from which Nadar’s portrait dates) to 1897 he governed France’s Central African colonies from his capital in Libreville.

The mirroring relationship between these images—one lost, but ineradicably inscribed in Barthes’s memory, the other found, but of minimal account in his thinking —is visible not merely as a consequence of their perfectly inverted compositions (a white man stood above seated slaves; a white man sat beneath standing chattel), but in the fact that the structure of “relations”26 which govern both images coincide in their essential utility to racial capitalism, and to the violent maintenance of white supremacy. If Casby’s portrait confirms for Barthes that “slavery has existed, not so far from us” (79), then what does de Brazza’s portrait confirm in its greater proximity—geographically, culturally, and politically—to a French intellectual writing in France? Barthes responds repeatedly to the portrait of Casby, an African American, but in the “that-has-been” of violently racist French colonial rule, incarnated in the figure of de Brazza, he finds no words—neither upon first encounter, nor after a period of sustained reflection.

Significantly, in both the lost slave market photograph and the de Brazza portrait, white men serve as central protagonists of the image, and as the central agents and makers of meaning in the historical conjunctures that each photograph frames (91). I would argue that these aversions and silences demonstrate Barthes’s freedom to reject the radical contiguity that the photograph creates between its material referent and its viewer, and that that freedom is useful precisely because “the referent adheres” (6). I would argue that the contiguity that a carnal medium like photography might create between Barthes’s body and the facts of French colonialism—the radical fleshly proximities that might issue from an unrestricted encounter with de Brazza’s portrait—risk a kind of contagion, a destabilization of both “affective” method and of sovereign self. It may be comforting to assume that these lacuna and elisions represent an instance in which Barthes “consumes aesthetically” (51) a meaning that is “too impressive” (36)—that he discovers a punctum in Nadar’s portrait which alleviates the political pressure of contending with this scene. But this would imply that the punctum can serve to inoculate its viewer against the politics of meaning, and this is a notion that Barthes never entertains or avows: that “punctual” seeing might serve to deflect shock.27

The matter of Barthes’s aversion to the material historicity of the photograph turns not merely on his indifference to the studium, and to what he construes as its tedious injunction to feign interest in the bromides of “the Operator”: “It is rather as if I had to read the Photographer’s myths in the photograph, fraternizing with them but not quite believing in them” (28). Barthes’s refusal to contend with the that-has-been of images to which he himself is connected, both by the transits of historical meaning and by the circuitry of colonial power, models a method of engaging with photography premised on a politics of strategic disavowal, and ratified by the strength of white feeling. I would argue that his various elisions, blind spots, and outright aversions to the residual matter that subtends photographic grain and pixel devolves around the disordering fact that racist histories of French colonial violence, of which he is a direct beneficiary, undergird his “political right to be a subject” (15), over and against those people he instrumentalizes as so many speechless objects in the evolution of his theory.

If Casby has no standing as an individual whose referent “adheres” to the photograph, if his presence in Avedon’s portrait registers only the fact of slavery, doesn’t his dis-individuation imply that he has no “punctual” existence, no “he-has-been”? What might this mean for blackness? Wendy Hui Kyong Chun writes that, “in terms of US slavery, dark skin became the mark of the natural condition of slavery through which all kinds of external factors—and the violence perpetrated on African slaves—became naturalized and ‘innate.’”28 What might this mean for Barthes’s canonical theory of photography?

In her pathbreaking essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Hortense Spillers recapitulates the inventory of physical and symbolic violences meted out against Africans and African Americans through the historical conjuncture of slavery into a post-emancipation present of “neo-enslavement,” addressing, in part, the profoundly generative nature of the captive body in the preservation of white subjectivity.29 Spillers describes the impossibility, for members of the captive community, of maintaining a coherent set of “biological, sexual, social, cultural, linguistic, ritualistic, and psychological” coordinates around a captive body under conditions of enslavement, in which attempts to preserve corporeal and psychic integrity are violently disrupted “by externally imposed meanings and uses,” which she then briefly enumerates:

1) the captive body becomes the source of an irresistible, destructive sensuality; 2) at the same time—in stunning contradiction—the captive body reduces to a thing, becoming being for the captor; 3) in this absence from a subject position, the captured sexualities provide a physical and biological expression of “otherness”; 4) as a category of “otherness,” the captive body translates into a potential for pornotroping and embodies sheer physical powerlessness that slides into a more general “powerlessness,” resonating through various centers of human and social meaning.30

I cannot help but hear an echo of Barthes’s ascription of the term “solacing Mammy” to the black woman in Van Der Zee’s 1926 portrait in Spillers’s foregoing lines. Against the normative term “body,” Spillers posits a hierarchical distinction in the context of slavery (and its ongoing aftermath) “between ‘body’ and ‘flesh,’” and she imposes “that distinction as the central one between captive and liberated subject-positions.” Thus, “before the ‘body’ there is the ‘flesh,’ that zero degree of social conceptualization that does not escape concealment under the brush of discourse, or the reflexes of iconography.” Such black flesh is ineluctably concealed, dis-individuated of its subjective specificity beneath “the brush of discourse”—concealed within the general field of Barthes’s studium—while it is simultaneously subjected to pathological forms of violence registered in the record of its passage through the eviscerations of slavery: “eyes beaten out, arms, backs, skulls branded, a left jaw, a right ankle, punctured; teeth missing, as the calculated work of iron, whips, chains, knives, the canine patrol, the bullet.”

Such desecration inscribes black flesh with specific meaning as the site of degenerate property incapable of self-possession and fundamentally available for violence, so that these “undecipherable markings on the captive body render a kind of hieroglyphics of the flesh whose severe disjunctures come to be hidden to the cultural seeing by skin color.” In effect, the studium effects an erasure of its own constitutive violence by displacing such violence to black flesh as evidence of its inherent degeneracy. The stigmatization of black skin veils the white violence that subjects it. This is how Casby’s face indexes slavery for Barthes “without mediation,” because for Barthes black skin is not a medium, an interface, a site through which meanings are mediated and onto which they are projected, but is rather a brute object: a dumb deictic thing that speaks “slavery!” If such a claim seems extreme, note how seamlessly the phrase “black skin” substitutes for “the Photograph” in establishing slavery’s fact without method or mediation: “[the Photograph] is never anything but an antiphon of ‘Look,’ ‘See,’ ‘Here it is’; it points a finger at certain vis-à-vis, and cannot escape this pure deictic language” (5).

Echoes of the Fanonian moment of epidermalization resound in Barthes’s text. Faced with the simultaneity of such viscerally and symbolically productive violence, Spillers responds: “We might well ask if this phenomenon of marking and branding actually ‘transfers’ from one generation to another, finding its various symbolic substitutions in an efficacy of meanings that repeat the initiating moments?”

In this light, perhaps Casby’s dis-individuation is reflective of the fact that the logic of photographic visibility and of temporal presence elaborated by Barthes is utterly permeated by the furtive dynamics and histories of white power, by its necessary disavowals, by its utter dependence upon acts and processes of racialization, normative logics of degeneracy, and by the forms of pleasure that whiteness derives from the various violences of possession, meted out in the exercise of self-possession. Casby surfaces in this Richard Avedon portrait only as a dis-individuated historical index, as a metonym for a general (enslaved/black) condition which he is made to embody in Barthes’s text, because the normative protocols of photographic visibility and legibility serve to veil the structuring power of whiteness, which disappears from view in Barthes’s reading of this portrait precisely at its blood-soaked natal scene: slavery.

Spillers writes about such symbolic “atomizations” of the captive black body—its semantic and physical dismembering into parts, or into texts for a general reading—that “we lose any hint or suggestion of a dimension of ethics, of relatedness between human personality and its anatomical features, between human personality and cultural institutions.”31 Perhaps all this means that Barthes’s “stupid metaphysics,” his willful “primitivism,” to follow Jonathan Beller’s beautiful formulation,

must steadfastly keep the histories of racial formation and political economy outside of the photographic frame to have evidence without method because otherwise, one might see that the evidence is the method: the historical and technical separation of subjects from their skin explicitly places racialization and photography on a continuum. 32

This is, to quote Barthes himself, “a vague, casual, even cynical phenomenology” (20) indeed.

Throughout Camera Lucida, Barthes summons the images of people so that they might sit wordlessly on the page, subsumed by his own history, subservient to the necessities of his grief, salient by virtue of their error or deformity, useful as instantiations of grand abstractions, either mythic or mundane, but wholly without speech: sans parole. Faced with Avedon’s portrait of William Casby, Barthes is incapable of asking, much less of imagining (as he did of Napoleon’s youngest brother, Jerome, at the outset of the book [3]): What might his eyes have seen?

Continues at “Sans Parole: Reflections on Camera Lucida, Part 2”

Cited in Geoffrey Batchen, “Palinode: An Introduction to Photography Degree Zero,” in Photography Degree Zero, ed. Geoffrey Batchen (MIT Press, 2009), 11.

Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” in diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer 1987), 70.

Chéla Sandoval, “Theorizing White Consciousness for a Post-Empire World: Barthes, Fanon, and the Rhetoric of Love,” in Displacing Whiteness: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism, ed. Ruth Frankenberg (Duke University Press, 1997), 90.

Fred Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” in Loss: The Politics of Mourning, eds. David Eng and David Kazanjian (University of California Press, 2003); Kaja Silverman, “The Gaze,” “The Look,” “The Screen,” chap. 4–6 in The Threshold of the Visible World (Routledge, 1996); Tina Campt, “The Lyric of the Archive,” chap. 3 in Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Duke University Press, 2012); Jonathan Beller, “Camera Obscura After All: The Racist Writing with Light,” chap. 6 in The Message Is Murder: Substrates of Computational Capital (Pluto Press, 2018).

Plainly, since the Winter Garden Photograph was not published the term iconic seems utterly misconceived. But the image stands as the pretext and urtext for Camera Lucida, and as a metonym for Barthes’s theorization of photography, so the photograph’s spectacular absence make it not merely a figure of great significance in regards to the book, but arguably the book’s preeminent figure.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (Hill and Wang, 1981), 42. All subsequent page references to this source are given inline. All emphasis in original.

Roland Barthes, Mythologies (Noonday Press/Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1972).

Sandoval, “Theorizing White Consciousness,” 86, 90.

Sandoval, “Theorizing White Consciousness,” 87.

Samira Kawash, “The Epistemology of Race: Knowledge, Visibility, Passing,” in Dislocating the Color Line: Identity, Hybridity and Singularity in African-American Literature (Stanford University Press, 1997), 130.

Later on in Camera Lucida, on page 42, Barthes gives some intimation that he might recognize that that “heterogenous” figure of the nuns contrasting with the soldiers issues from imperial violence and colonial history, when he writes that “a whole causality explains the presence of the ‘detail’: the Church implanted in these Latin American countries, the nuns allowed to circulate as nurses, etc.,” but he gives no indication that he recognizes their presence as in fact part of an underlying continuum of homogeneity in which Central and South America are, and have been, constant targets for imperialist violence. See Ariella Azoulay, “Unlearning Decisive Moments of Photography,” in Still Searching…, Fotomuseum Winterthur, 2018 →.

Silverman, The Threshold of the Visible World, 183.

More on this image in Part 2 of this essay, forthcoming in e-flux journal.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 67.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 67.

“Another, louder voice urged me to dismiss such sociological commentary; looking at certain photographs, I wanted to be a primitive, without culture.” Camera Lucida, 7.

Oxford English Dictionary, online ed., 2019.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture eds. Cary Nelson, Lawrence Grossberg (University of Illinois Press, 1988), 280, 281.

Jay Prosser, “Skin Memories,” in Thinking Through the Skin, eds. Sara Ahmed and Jackie Stacey (Routledge, 2001), 52.

Moten, “Black Mo’nin’,” 71.

Note: Richard Avedon has always captioned this portrait “William Casby, born in slavery, March 1963,” where Barthes’s Camera Lucida changed the caption to “William Casby, born a slave. 1963.”

Gospel of St. John, chap. 20, verse 25, The Holy Bible: Old and New Testaments, King James Version (Duke Classics, 2012), 2423.

Charles Sanders Peirce, quoted in Brian Massumi, “The Future Birth of the Affective Fact: The Political Ontology of Threat,” in The Affect Theory Reader, ed. Melissa Gregg (Duke University Press, 2010), 64.

Massumi, “The Future Birth of Affective Fact,” 64.

Beller, The Message Is Murder, 105–6.

The term “relations” must be qualified by quotation marks since in both instances, white men are depicted with their docile black property.

For more on this model of psychic absorption and deflection of shock, see Walter Benjamin, “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” in The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006).

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “Introduction: Race and/as Technology; or, How to Do Things With Race,” Camera Obscura 24, no. 1 (2009), 11.

Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” 76.

Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” 67. All subsequent quotes from this source are taken from page 67 unless otherwise noted. All emphasis in original.

Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” 68.

Beller, The Message Is Murder, 109.

Sans Parole: Reflections on Camera Lucida, Part 2

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

Part 2: Shouts, Moans, Musics

Even though the captive flesh/body has been “liberated,” and no one need pretend that even the quotation marks do not matter, dominant symbolic activity, the ruling episteme that releases the dynamics of naming and valuation, remains grounded in the originating metaphors of captivity and mutilation so that it is as if neither time nor history, nor historiography and its topics, shows movement, as the human subject is “murdered” over and over again by the passions of a bloodless and anonymous archaism, showing itself in endless disguise.—Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book”1

5.

always carries its referent with itself, both affected by the same amorous or funereal immobility, at the very heart of the moving world: they are glued together, limb by limb, like the condemned man and the corpse in certain tortures … as though united in eternal coitus. (5–6, emphasis mine)

the photograph must be silent (there are blustering photographs, and I don’t like them): this is not a question of discretion, but of music. Absolute subjectivity is achieved only in a state, an effort, of silence (shutting your eyes is to make the image speak in silence). The photograph touches me if I withdraw it from its usual blah-blah. (53–55)

from the moment I first laid eyes on them, I have struggled to understand what exactly these images were saying, and what it was they told us about photography and the making of community in diaspora. But I also came to realize that what was so captivating about them is not only what I was seeing, but what I was hearing as I looked at them—a playful yet insistent hum that I found difficult and, frankly, a mistake to ignore.5

I would like to suggest that thinking about images through music deepens our understanding of the affective registers of family photography and helps us understand how such images are mobilized by black families as a practice that articulates linkage, relation, and distinction in diaspora.9

Mingus thinks that in the absence of a law of movement to break, calypso falls into the random constraint of a death spiral. However, Dudley shows how the maintenance of the circle’s integrity requires the legal procedure of an articulated ensemble, what Olly Wilson calls a “fixed rhythmic group” whose “rhythmic feel is not produced by a single pattern … but is a composite generated by several instruments that play repeated interlocking parts.” No hegemonic single pattern means no sole instrument or player responsible for that pattern’s upkeep. There is, rather, a shared responsibility that makes possible the shared possibilities of irresponsibility.17

is manifest in Barthes as the exclusion of the sound/shout of the photograph; and … in the fundamental methodological move of what-has-been-called-enlightenment, we see the invocation of a silenced difference, a silent black materiality, in order to justify a suppression of difference in the name of (a false) universality.20

Emmett Till’s face is seen, was shown, shone. His face was destroyed (by way of, among other things, its being shown: the memory of his face is thwarted, made a distant before-as-after effect of its destruction, what we would never have otherwise seen). It was turned inside out, ruptured, exploded, but deeper than that it was opened. As if his face were truth’s condition of possibility, it was opened and revealed. As if revealing his face would open the revelation of a fundamental truth, his casket was opened, as if revealing the destroyed face would in turn reveal, and therefore cut, the active deferral or ongoing death or unapproachable futurity of justice.25

bears the trace of a particular moment of panic when, “under the knell of the Supreme Court’s all deliberate speed,” there was massive reaction to the movement against segregation … So that the movement against segregation is seen as a movement for miscegenation and, at that point, whistling or the “crippled speech” of Till’s “Bye, Baby” cannot go unheard.26

If to remember is to provide the disembodied “wound” with a psychic residence, then to remember other people’s memories is to be wounded by their wounds. More precisely, it is to let their struggles, their passions, their pasts, resonate within one’s own past and present, and destabilize them.29

6.

quotidian practice of refusal I am describing is defined less by opposition or “resistance,” and more by a refusal of the very premises that have reduced the lived experience of blackness to pathology and irreconcilability in the logic of white supremacy. Like the concept of fugitivity, practicing refusal highlights the tense relations between acts of flight and escape, and creative practices of refusal—nimble and strategic practices that undermine the categories of the dominant.41

I then realized that there was a sort of link (or knot) between Photography, madness and something whose name I did not know. I began by calling it: the pangs of love … Is one not in love with certain photographs? … Yet it was not quite that. It was a broader current than a lover’s sentiment. In the love stirred by Photography (by certain photographs), another music is heard, its name oddly fashioned: Pity. I collected in a last thought the images which had “pricked” me (since this is the action of the punctum), like that of the black woman with the gold necklace and the strapped pumps. In each of them, inescapably, I passed beyond the unreality of the thing represented, I entered crazily into the spectacle, into the image, taking into my arms what is dead, what is going to die, as Nietzsche did when, as Podach tells us, on January 3rd, 1889, he threw himself in tears on the neck of a beaten horse: gone mad for Pity’s sake. (116–17)

The history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist. Blackness—the extended movement of a specific upheaval, an ongoing irruption that anarranges every line—is a strain that pressures the assumption of the equivalence of personhood and subjectivity. While subjectivity is defined by the subject’s possession of itself and its objects, it is troubled by a dispossessive force objects exert such that the subject seems to be possessed—infused, deformed—by the object it possesses.45