Keats Fanny Brawne

六百八十一

元遺山《種松》云:"百錢買松羔,植之我東墻。汲井涴塵土,插籬護牛羊。一日三摩挲,愛比添丁郎。昨宵入我夢,忽然變昂藏。昂藏上雲雨,慘澹含風霜。起來月中看,細鬣錯針芒。惘然一太息,何年起明堂?鄰叟向我言,種木本易長。不見河畔柳,顧盼百尺強。君自作遠計,今日何所望?"按白樂天《栽松》第一首云:"栽植我年晚,長成君性遲。如何過四十,種此數寸枝。得見成陰否,人生七十稀";又《種荔枝》云:"紅顆珍珠誠可愛,白鬚太守亦何癡。十年結子知誰在,自向庭中種荔枝"(一作戴叔倫《荔枝》);《東溪種柳》云:"松柏不可待,楩柟固難移。不如種此樹,此樹易榮滋";李端《觀鄰老栽松》(一作耿湋詩)云:"雖過老人宅,不解老人心。何事殘陽裏,栽松欲待陰";施肩吾《誚山中叟》:"老人今年八十幾,口中零落殘牙齒。天陰傴僂帶嗽行,猶向巖前種松子";王荊公《酬王濬賢良松泉》第一首:"我移兩松苦不早,豈望見渠身合抱";東坡《種松得徠字》:"我今百日客,養此千歲材自注:時去替不百日。茯苓無消息,雙鬢日夜摧。古今一俯仰,作詩寄餘哀";朱竹垞卷十七《曝書亭偶然作‧之六》云:"雨裏芭蕉風外楊,水中菡萏岸篔簹。衰翁愛植易生物,不願七年栽豫章。"參觀《埤雅》卷十三引諺"白頭種桃",《爾雅翼》卷十作"頭白可種桃。"又《曲洧舊聞》卷三引諺:"頭有二毛好種桃,立不踰膝好種橘"(吳欑《種藝必用》[《永樂大典》一萬三千一百九十四"種"字]亦引此諺)。F.C.S. Schiller,Our Human Truths, p. 132: "The quality of vital activities depend upon the time-scale of life. For a life that lasted for centuries it would be worthwhile to plant groves of sequoias , whereas the shorter life would have to be content with radishes."

Hyder E. Rollins, ed., Letters of John Keats, I, p. 232: "... it is a false notion that more is gained by receiving than giving — no, the receiver & the giver are equal in their benefits — The flower, I doubt not, receives a fair guerdon from the Bee -— its leaves blush deeper in the next spring — and who shall say between Man & Woman which is the most delighted?" 按此事終古聚訟。Hesiod, Melampodia, iii: "... Teiresias saw two snakes mating on Cithaeron and... when he killed the female, he was changed into a woman, & again, when he killed the male, took again his own nature. This same Teiresias was chosen by Zeus & Hera to decide the question whether the male or the female has most pleasure in intercourse [Hans Licht, Sexual Life in Ancient Greece, tr. J.H. Freese, p. 242: "... since he had experienced both"]. And he said: 'Of ten parts a man enjoys one only; but a woman's sense enjoys all ten in full.' For this Hera was angry & blinded him" (Hesiod, tr. H.G. Evelyn-White, "The Loeb Classical Library", p. 269). Casanova "Tiresias, who was once a woman, has given a correct though amusing decision. The most conclusive reason is that if the woman's pleasure were not the greater nature would be unjust. Nature has given to women this special enjoyment to compensate for the pains they have to undergo. What man would expose himself, for the pleasure he enjoys, to the pains of pregnancy & the dangers of childbed? But women will do so again & again" (The Memoirs of G. Casanova, tr. Arthur Machen, The Casanova Society, 1922, XI, p. 134). 可謂強詞奪理。Rudolf Haym, Die Romantische Schule, 4te Aufl. S. 576 論 Fr. Schlegel 小說 Lucinde 有云:"Der höchste Grad dieser [Liebes] Kunst zeigt sich als 'bleibendes Gefühl harmonischer Wärme' und welcher Jüngling das hat, 'der liebt nicht mehr bloss wie ein Mann, sondern zugleich auch wie ein Weib.' Als die witzigste und darum schönste unter den Situationen der Freude wird es gepriesen, wenn Mann und Frau im Liebesspiel die Rollen tauschen, um so das Männliche und Weibliche zu vollenden." 殆以為顛鸞倒鳳、覆雨翻雲,真能轉陰換陽,合兩儀為太極耶?信癡人語矣!咄咄夫《增補一夕話》卷四:"夫問妻曰:'男女交合,男快活?抑女快活?'妻曰:'是男。譬如人在浴盆中洗澡,畢竟是人快活。難道是浴盆快活不成?'夫曰:'不然。譬如消息在耳朵內轉動,畢竟是耳朵快活。難道是消息快活不成?'"孫兆溎《花箋錄》卷十八載韓承烈所撰《耳鼓》中有《鎖吉翥》一則記鎖善淫,而具偉甚,無所施技,因從道士學太陰脫胎法,化為女身,道士喻之曰:"美食在盤,嗜之甘者口耳,於匕箸何與焉!"皆可佐 Teiresias 瞽叟張目。徐學謨《歸有園麈談》云:"男子好色,如渴飲漿;女子好色,如熱乘涼。"句整韻諧,而羌不識意義所在。馮猶龍《笑府》云:"婦臨產創甚,與夫誓曰:'以後不許近身。'及生一女,議名,妻曰:'喚做招弟罷。'"可證 Casanova

〇遺山《放言》云:"長沙一湘纍,郊島兩詩囚";《別周卿弟》云:"苦心亦有孟東野,真賞誰如高蜀州。"按世人衹知《論詩絕句》之"東野悲鳴死不休,高天厚地一詩囚"耳。

〇《唐音癸籖》卷四云:"用'元氣'二字最多者劉長卿",舉《登揚州栖靈寺塔》:"盤梯接元氣,半壁棲夜魄"、《登東海龍興寺高頂望海簡演公》:"元氣遠相合,太陽生其中"、《送杜越江佐覲省往新安江》:"色混元氣深,波連洞庭碧"、《岳陽館中望洞庭湖》:"疊浪浮元氣,中流沒太陽"、《自鄱陽還洞庭道中寄褚徵君》"元氣連洞庭,夕陽落波上"等詩為證。按當云:"以'元氣'二字寫景者,長卿最多。"則語意圓切矣。後來如陳簡齋《感懷》之"青青草木浮元氣"、《登岳陽樓》之"日落君山元氣中",即從長卿來,而顧氏注不知引長卿《洞庭湖》之"疊浪浮元氣",可謂失之眉睫。元遺山詩中,用"元氣"二字尤多,其描狀景物者,如《亭》云:"宿雲淡野川,元氣浮草木";《南湖先生雪景乘騾圖》云:"異色變慘澹,元氣開洪濛";《游承天懸泉》:"太初元氣未凝結,更欲何處留胚胎";《太室同希顏賦》:"元氣有遺形"等,亦得之簡齋,施注亦未詳也。《別李周卿‧之二》云:"風雅久不作,日覺元氣死";《蕭仲植長史齋》:"是公技進不名技,元氣淋漓隨咳唾";《嘯臺感遇》:"豈知大人先生獨立萬物表,太古元氣同胚胎",則非寫景。又按《全金詩》卷三十四劉昂霄《趙村晚望》云:"天地浮元氣,山河半夕陽",甚似遺山。卷三十李獻能《榮陽古城登覽寄裕之》、卷三十四田紫芝《夜雨寄元敏之兄弟》、卷四十三李汾《陜州》、《再過長安》、《汴梁雜詩》、李獻甫《圍城》、《驟雨》、《資聖閣登眺》諸七律,波瀾意度皆極類遺山,肌理稍懈耳。概風氣化移,同聲而非獨詣,《甌北詩話》卷八之言,未見其全也。他如卷三十三張本《九日月中對菊‧之五》云:"一書草就渾衣臥,恨殺東方不肯明",卷四十四李俊民《和王季文襄陽變後》云:"蛟龍不是池中物,燕雀休嗤壟上人"【施注已引】,與遺山詩句為暗合乎?為蹈襲?亦耐尋味。

〇施注甚陋,尋常詩句皆當面錯過。如卷三《曲阜紀行》第九首:"所得不毫髮,咎責滿八區",施不知其本昌黎《寄崔二十六立之》:"歡華不滿眼,咎責塞兩儀";卷二《贈鶯》:"獨愛黃栗留,婭姹如稚女。笑啼啼又笑,宛轉工媚嫵",施不知其本歐公《啼鳥》之"黃鸝顏色已可愛,舌端啞咤如嬌嬰",及蘇子美《雨中聞鶯》之"嬌騃人家小女兒,半啼半語隔花枝";卷三《赤壁圖》:"事殊興極憂思集,天澹雲閑今古同",施注:"'事殊',杜句按見《渼陂行》",而不知"天澹"句之出小杜《宣州開元寺水閣》詩(亦正如卷十《和白樞判》之以老杜之"白日放歌須縱酒",對小杜之"清朝有味是無能");卷四《常山妷》詩:"回頭却看元叔綱,鼻涕過口尺許長",施不知其本王子淵《童約》之"目淚下落,鼻涕長一尺";卷五《南湖先生雪景乘騾圖》:"一旦拂衣去,學劍事猿公",施注:"李白詩:'少年學劍術,凌轢白猿公'",而不知其用長吉《南園》第七首之"見買若耶溪水劍,明朝歸去事猿公";卷九《四哀詩‧李長源》:"同甲四人三横霣,此身雖在亦堪驚",施不知其用簡齋《臨江仙》詞之"二十餘年成一夢,此身雖在堪驚";《寄答仰山謙長老》:"一鳥不鳴山更幽",施不知其逕取荊公《鍾山即事》結句;卷九《外家南寺》:"白頭來往人間偏,依舊僧房借榻眠",按施不知其用荊公《和惠思歲二日絕句》第一首:"為嫌歸舍兒童聒,故就僧房借榻眠";卷十《同嚴公子大用東園賞梅》:"佳節屢從愁裏過",施不知其用老泉《九日和韓魏公》之"佳節已從愁裏過";《贈馮內翰》第一首:"扶路不妨驢失脚",施注引陳希夷墮驢事,全不相干,此自用山谷《老杜浣花溪圖》之"兒呼不蘇驢失脚",《誠齋集》卷百十四舉為山谷句樣者也;卷十四《贈寫真田生‧之二》:"情知不是裴中令,一片靈臺狀亦難",施不知其用裴晉公《自題寫真》之"一點靈臺,丹青莫狀"(《全唐文》卷五三八);卷十四《論詩‧之三》:"鴛鴦繡了從教看,莫把金針度與人",施不知其本《五燈會元》卷十四惟照語,改"君"字為"教"字。此類尚多,皆《談藝錄》所未及也。【《鷗陂漁話》卷一:"朱梓廬《壺山吟稿》有《題遺山墓碑搨本》詩,自注云:'碑陰有魏初、姜彧記云:"彧與初嘗先辱先生教誨,又聞先生之言曰:'某身死之日,不願有碑誌也。墓頭樹三尺石,書曰:"詩人元遺山之墓",足矣!'彧與初適按部河東,得拜先生墓下,因買石刻之,時至元十九年。"'施北研《附錄》佚此。"】【"身無鳧舄將焉往,手有牛刀恐亦難。"按陳德武《白雪遺音‧望海潮‧和韻寄別葉睢寧》云:"纔試牛刀,俄驚鳧舄。"】【《媿生叢錄》卷二:"《贈張文舉御史》詩:'會有先生引鏡年'本《文選》王融《三月三日曲水詩序》善注,施注誤。"】

〇遺山《病中病因食豬動氣而作》:"杯杓歸神誓,垣墻任佛踰",施無注。按閩、粵有肴名"佛跳墻",蓋砂罐燉鷄也。觀遺山語,則此謔由來舊矣!周櫟園《書影》卷六引李子田云:"俗云:'姨娘懷裏,聞得娘香。'此語甚俚,然元遺山《哭姨母隴西君》詩云:'竹馬青衫小小郎,阿姨懷袖阿娘香'【按見《遺山集》卷十二《姨母隴西君諱日作》第一首】,則其語亦遠矣。"可參觀。

〇遺山《張主簿草堂賦大雨》云:"厚地高天如合圍";《論詩三十首》云:"高天厚第一詩囚。"按陳簡齋《友人惠石兩峯》云:"暮靄朝曦一生了,高天厚地兩峯閒。"簡齋好用"了"字,第四百五十六則論《簡齋集》卷十《清明》詩,已略舉其句中用"了"字諸例,其句尾用"了"字者,舍"暮靄"句外,尚有如《送善相僧超然》:"鼠目向來吾自了"、《題向伯共過峽圖》:"柱天動業須君了"、《送客出城西》:"殘年正爾供愁了"等。蓋少陵《洗兵馬》云:"整頓乾坤濟時了",山谷《病起荆江亭即事》仿之云:"十分整頓乾坤了",爾後遂成詩家樣子句。遺山《十二月十六日還冠氏》之"一瓶一缽平生了"、《出都》之"從教盡剗瓊華了"、《寄答商孟卿》之"書來且只平安了"、《追錄洛中舊作》之"人間只怨天公了"、《追懷曹徵君》之"因君錯怨天公了"、《晉溪》之"乾坤一雨兵塵了"、《元都觀桃花》之"一杯盡吸東風了"、《贈李春卿》之"丹房藥鏡平生了",厥例尤多。簡齋《十月》云:"涼風又落宮南木,老雁長雲行路難";《重陽》云:"老雁孤鳴漢北州";遺山《雨後丹鳳門登眺》云:"老雁叫雲秋更哀";《寄答商孟卿》云:"老雁叫羣江渚深",他人詩中亦少見。【遺山弟子王惲《秋澗大全集》卷十四《中秋月》:"一杯儘吸清光了,洗我平生芥蔕腸";《南城納涼晚歸》:"一杯粥了從髙卧,須信閒身等策勲";《八月十一日夜坐》:"大家但使康強了,未害窮愁老此生";《送蕭四祖北上》:"中原有幸經綸了,天外高鴻本自冥";卷十六《和郝子貞見贈之二》:"薄田粗足充飢了,衰俗無依奈物輕";卷卅二《獅猫》:"夢裏鼠山京觀了,午欄花影淡離離。"】【《養一齋詩話》卷八舉遺山複句,補甌北之遺,亦及以"了"字煞尾句太多。】

【《全唐文》卷八九六羅隱《論甲子年事》:"歷歷見趙家之遺臺老樹。"遺山《出都》第二首:"老樹遺臺秋更悲"等句用此,北研未注。】

【又卷二十三《壬子寒食》:"兒女青紅笑語嘩,秋千環索響嘔啞。今年好個明寒食,五樹來禽恰放花。"(簡齋《清明》第一首:"街頭女兒雙髻鴉,隨蜂趁蝶學夭邪。東風也作清明節,開遍來禽一樹花。")】

【吳景旭《歷代詩話》卷六十二謂遺山詩"養和懲往失,扶老念時須"本之宇文叔通《和高子文秋興》:"散步雙扶老,棲身一養和。"按詩見《中州集》卷一,遺山有註。張師錫《老兒詩》亦云:"養和屏作伴,如意拂相連。"皮日休《五貺詩‧之四‧烏龍養和》("壽木拳數尺,天生形狀幽。……料君携去處,烟雨太湖舟");張雨《貞居先生詩集》卷五《自笑》:"已裁斑竹將扶老,更剪蟠枝作養和";《太平廣記》卷三十八《李泌》(《鄴侯外傳》):"採怪木蟠枝,持以隱居,號曰'養和'。"似又非屏。】

〇遺山《贈蕭漢傑》:"射虎將軍右北平,短衣憔悴宿長亭。"按王漁洋《題尤展成新樂府》第二首云:"旗亭被酒何人識,射虎將軍右北平。"《精華錄訓纂》卷六下衹引《史記》李廣事而已,不知其用遺山語。漁洋《居易錄》甚稱遺山詩者。又遺山《寄答飛卿》:"古來獻玉猶難售,此日聞韶本不圖。"按嚴又陵《見十二月初七日邸鈔作》"平生獻玉常遭刖,此日聞韶本不圖"全本之。

〇遺山《論詩》云:"詩家總愛西崑好,獨恨無人作鄭箋。"按袁伯長《清容居士集》卷四十八《書鄭潛庵李商隱詩選》云:"其源出於杜拾遺,晚自以不及,故別為一體,直為訕侮,非若為魯諱者。使後數百年,其詩禍之作,當不止流竄嶺海而已也。桷往歲嘗病其用事僻昧,間閱《齊諧》、《外傳》諸書,籖於其側,冶容褊心,遂復中止。"胡孝轅《唐音癸籤》卷三十二云:"唐詩有兩種不可不注。今杜詩注如彼,而商隱一集迄無人能下手。始知實學之難。友人屠用明嘗勸予為義山集作注"云云。袁、胡二事,皆馮注所未道者。

〇《清容居士集》卷三《車行》云:"隆如龜戴殼,縛如蠶裹繭。禪趺恣掀簸,尸寢作瞑眩。初疑肝膽傾,漸覺手足顫。兩耳傳鳴雷,雙眸瞥飛電。縈迴蟻旋磨,局促蟲負版。氣奔驚七還,心嘔復三咽。揩摩髀消肉,舍棄足成趼。"按黃石牧《堂集》卷三十五《騾輿》云:"或恣其擺蕩,如遭篩米農。大箕納肉軀,簸揚輕以鬆。或縱其欹側,亘作高低容。如眾舴艋去,而被風浪衝。或為上下顛,掀如杵臼舂。(中略)危坐擁茵褥,支體相撞摏。橫陳彌摯曳,頂踵摩成癰。攪亂心肺肝,顛倒在一胸";李分虎《香草居集》卷五《詠驘車》云:"俛首褰簾帷,盤膝倚包裹。頗似老衲參,又若新婦坐。(中略)傍有圉人軀,時作醉尉呵。(中略)轉側不暫寧,偃仰詎能臥。(中略)目昏五色花,頭眩百轉磨。"宣統二年《小說時報‧蓴鄉漫錄》云:"京中驢車,乘時極顛簸,曾重伯戲作一聯云:'兩塊鼈裙搓麵餅,一雙鴿蛋滾湯圓。'上句言女,下句言男也。"

【《遺山集》卷十一《惠崇蘆雁》第三首:"江湖牢落太愁人,同是天涯萬里身。不似畫屏金孔雀,離離花影淡生春。"按溫飛卿《更漏子》首章:"驚塞雁,起城烏,畫屏金鷓鴣。"《白雨齋詞話》說之曰:"此言苦者自苦,樂者自樂。"甚有悟心。遺山此作,實得溫詞之旨。《山谷內集》卷七《睡鴨》云:"山鷄照影空自愛,孤鸞舞鏡不作雙。天下真成長會合,兩鳧相倚睡秋江。"《賓退錄》卷十亦謂題畫作,正復同意。】

〇吳復編樓卜瀍注《楊鐵厓古樂府》卷九《買妾》云:"買妾千黃金,許身不許心。使君聞有婦,夜夜白頭吟。"按此意同曹鄴《古詞》所謂"郎妻自不重,於妾欲如何",而措詞稍婉。《唐詩歸》卷三十四選鄴此詩,伯敬評以為"深於妬妬,亦有至理";友夏以為"機警女郎之言,斷得惡少年心服。"

【《鐵厓逸編》卷二《濮州娘》云:"朱鬕氏按指劉福通掠女婦,擇白腯者一狎,即付湯火,熬膏,為攻城火藥。"按周櫟園《書影》卷二引《雜志》云:"常開平每出師,夜必御一婦,曉輒斷其頭以去。"二事殊類。】

〇《鐵厓逸編》卷五《題履元陳君萬松圖》自跋云:"子昭工畫仕女花木,予懼其情過粉黛,則氣乏風雲,故書此詩以遺之。"按元遺山《王都尉山水》:"自是秦樓畫眉手,不能辛苦作荊關",亦有此意。

〇白香山詩詞意多複,如《紫薇花》云:"獨立黃昏誰是伴?紫薇花對紫薇郎"《白氏文集》卷十九,而《紫薇花》又云:"紫薇花對紫微翁";《浩歌行》云:"欲留年少待富貴,富貴不來年少去",而《短歌行》又云:"彼來此已去,外餘中不足。少壯與榮華,相避如寒燠",不勝一一舉。《問劉十九》云:"綠蟻新醅酒,紅泥小火爐。晚來天欲雪,能飲一杯無?"世所傳誦,而《招東鄰》云:"小榼二升酒,新簟六尺牀。能來夜話否?池畔欲秋涼",亦同一機杼也。

〇香山《時世粧》云:"烏膏註唇唇似泥,雙眉畫作八字低。妍媸黑白失本態,粧成盡似含悲啼";《代書詩一百韻寄微之》云:"風流誇墜髻,時世鬥啼眉。"按《全後漢文》卷四十一載《風俗通》佚文,亦道"愁眉"、"啼粧"。又《唐書‧五行志》、蘇老泉《吳道子畫五星贊》皆道"烏唇"。又徐鉉《徐公文集》卷三《夢游‧一》:"檀的慢調銀字管";《二》:"含詞忍笑膩于檀。"

〇香山《松聲》云:"南陌車馬動,西鄰歌吹繁。誰知兹檐下,滿耳不為喧。"按末五字庶幾與淵明夢中神遇。此乃有聲而亦無聲,非《琵琶行》所謂"無聲勝有聲"也。阮圓海《詠懷堂詩‧戊寅詩‧緝汝式之見過谷中》:"坐聽松風響,還嫌谷未幽。"

〇《詩人玉屑》卷二十引東坡《跋李王所書》六言詩,其詞云:"空林有雪相待,野路無人獨還。"按此顧況《歸山》絕句(一作張繼)。後山《東禪》云:"邂逅無人成獨往,殷勤有月與同歸",天社無注,當以此二語參之。

〇《詩人玉屑》卷十九黃玉林云:"唐皇甫冉《問李二司直》詩云:'門外水流何處?天邊樹遶誰家?山絕東西多少?朝朝幾度雲遮?'此蓋用屈原《天問》體。荆公《勘會賀蘭山主》絕句:'賀蘭山上幾株松?南北東西共幾峯?貿得住來今幾日?尋常誰與坐從容?'全用其意。此體甚新,詩話未有拈出者。"按王無功《在京思故園見鄉人問》中段云:"殷勤訪朋舊,屈曲問童孩:衰宗多弟姪,若個賞池臺?舊園今在否?新樹也應栽?柳行疏密布?茅齋寬窄裁?經移何處竹?別種幾株梅?渠當無絕水?石計總生苔?院果誰先熟?林花那後開?羇心祗欲問,為報不須猜"云云,截去首尾,便成此體(《唐詩歸》卷一鍾亦欲刪去末二句),求之《天問》,稍遼遠矣。《陳止齋集》卷二《懷石天民》於無功之作擬議以成變化(見第四一四則)。李端《逢王泌自東京至》前四句云:"逢君自鄉至,雪涕問田園:幾處生喬木?誰家在舊村?"云云,亦此體。明凌雲翰《柘軒集》卷一《畫七首‧之四》云:"問訊南屏隱者:草堂竹樹誰栽?昨夜幾時雨過?山禽幾個飛來?"《燉煌曲子詞‧南歌子》二首,前一首云:"斜影珠簾立,情事共誰親?分明面上指痕新,羅帶同心誰綰?甚人踏裰裙?蟬鬢因何亂?金釵為甚分?紅妝垂淚憶何君?分明殿前直說,莫沉吟。"(後一首則逐事答云:"自從君去後,無心戀別人。夢中面上指痕新。羅帶同心自綰,被猻兒踏裰裙。蟬鬢朱簾亂,金釵舊股份。紅妝垂淚哭郎君,信是南山松柏,無心戀別人。")《樂府羣珠》卷四無名氏《朱履曲‧偷期》第一首云:"因甚麼蓬鬆鬀髻?因甚麼氣喘微微?脊梁上都是土和泥?因甚麼眼皮兒慢?因甚麼主腰兒低?因甚麼裩襠兒上濕?"(第二首逐句答云:"貪春色蓬鬆鬀髻,蹴秋千氣喘微微,靠蕭牆惹下這土和泥,貪針指眼皮兒慢,身子瘦主腰兒低,恰纔採紅花惹下些露濕。")王次回《疑雨集》卷四《臨行口占為阿鎖下酒》:"問郎燈市可曾遊?可買香絲與玉鈎?可有繡簾樓上看,打將瓜子到肩頭?"

六百八十二

Plotin, Ennéades, tr. Bréhier ("Collection des Universités de France"), V. viii. 2: "Considérons... des beautés naturelles.... N'est-ce pas dans tous les cas une forme, venue du générateur à l'engendré, comme dans les arts, disions-nous, elle vient des arts à leurs produits?" (V, pp. 136-7). Plato, The Sophist, 265e: "... things people called natural are made by divine art, & things put together by man out of those as materials are made by human art" ("The Loeb Class. Lib.", tr. H.N. Fowler, p. 449). 即 Thomas Browne,Religio Medici, P. I, §16: "In brief, all things are artificial; for Nature is the art of God" (Paul Shorey,Platonism Ancient & Modern, p. 197 所言可印證). E.R. Curtius 謂 Macrobius 始言 "das Dichtwerk ist dem Kosmos vergleichbar... eine grosse Ähnlichkeit zwischen... dem deus opifex und dem poeta" (Europäische Literatur und Lateinisches Mittelalter, 2te Aufl., S. 441-2),不知 Plato 等已發其意。Milton C. Nahm, The Artist as Creator 考論 "The great analogyof the srtist to God" (pp. 55 ff.),亦失引此,并未及 Macrobius

Enn., I. vi. 8: "Enfuyons-nous donc dans notre chère patrie... Comme Ulysse, qui échappa, dit-on à Circé la magicienne et à Calypso" etc. (I, p. 104); V. ix. 1: "Ils se plaisent en cette région de vérité qui est la leur, comme des hommes, revenus dune longue course errante, se plaisent dans une patrie bien gouvernée" etc. (V, pp. 161-2). 按此可補余 "The Return of the Native" Proclus, Elements of Theology, Prop. 33, 35, 146 僅言 "revert to the beginning", "revert upon the cause" 等 (Eng. tr. E.R. Dodds, pp. 37, 39, 129),未以歸家返國為喻也。參觀 Seneca, Epistulae morales, LXV. 16: "Animum, qui gravi sarcina pressus explicari cupit et reverti ad illa, quorum fuit"; LXXIV. 12: "Sursum illum vocant initia sua" ("The Loeb Classical Library", I, p. 452; II, p. 206);又 Emily Bronte: "The Prisoner": "Then dawns the Invisible; the Unseen its truth reveals; / My outward sense is gone, my inward essence feels: / Its wings are almost free — its home, its harbour found, / Measuring the gulf, it stoops & dares the final bound";又 Journal des Goncourt, 5 Avril, 1864 (Édition définitive, II, p. 149): "En littérature, on commence à chercher son originalité laborieusement chez les autres, et très loin de soi… plus tard on la trouve naturellement en soi… et tout près de soi";又《朱子語類》卷三十一論"回也,三月不違仁"云:"橫渠內外賓主之說極好,譬如一屋子,是自家為主,朝朝夕夕時時只在裏面。顏子或有出去時節,便會向歸。其餘是賓,或一日一至,或一月一至";卷一百十八舉"萬物皆備於我"一章:"今之為學,須是求復其初,真做到聖賢地位,方是全得本來之物而不失。人之為學,正如說恢復相似,且如東南亦自有許多財賦,許多兵甲,儘自好了,如何必要恢復?只為祖宗元有之物,須當復得;若不復得,終是不了";卷一百二十四:"陸子靜說'良知良能',不可謂不是。但說人便能如此,不假修為存養,此却不得。譬如旅寓之人,自家不能送他回鄉,但與說云:'你自有田有屋,大段快樂,何不便回去?'那人既無資送,如何便回去得?"他如 Virgil, Aeneid, IV. 347: "Hic amor, haec patria est"; Propertius, II. xi. 25-6: "tu mihi sola domus, tu, Cynthia, sola parentes, / omnia tu nostrae tempora laetitiae" 均相發明。又按 V. p. 162 Bréhier 註云:"chez lui [Plotin], le retour d'Ulysse à Ithaque est le symbole de l'initiation à la vie divine"。據 H. Weber, La Création poétique au 16e siècle en France, I, p. 133 論 "la théorie de la vérité cachée",記 "Dorât explique qu'Ulysse est l'homme à la recherche de la sagesse et du bonheur symbolisés par Pénélope et Ithaque"。餘見第七百一則論 Heine: "An meine Mutter"、第七五一則論《老子》"反者道之動"。

, II. ii. 1: "C'est un mouvement qui revient sur lui-même, mouvement de la conscience, de la réflexion et de la vie; jamais il ne sort de son cercle...【et de plus il [le mouvement] doit être celui qui est】le mouvement circulaire" (II, p. 21); IV. iv. 16: "Placez le Bien au centre, l'intelligence en un cercle immobile et l'âme en un cercle mobile et mû par le désir" (IV, p. 117). 按參觀 Plato, Laws, 898a: "... the motion which moves... always round some center, being a copy of the turned wheels... has the nearest possible kinship & similarity to the revolution of reason" ("The Loeb Classical Library", tr. R.G. Bury, II, p. 345)。又 Proclus, Elements of Theology, Prop. 146: "In any divine procession the end is assimilated to the beginning, maintaining by its reversion thither a circuit without beginning & without end" (tr. E.R. Dodds, p. 129). 又 Hegel, Phänomenologie des Geistes, "Vorrede": "Es [das Wahre] ist das Werden seiner selbst, der Kreis, der sein Ende als seinen Zweck voraussetzt und zum Anfange hat... "; Logik, II Teil, iii Absch., 3 Kap.: "Vermöge der aufgezeigten Natur der Methode stellt sich die Wissenschaft als ein in sich geschlungener Kreis dar, in dessen Anfang, den einfachen Grund, die Vermittlung das Ende zurückschlingt; dabei ist dieser Kreis ein Kreis von Kreisen" (Sämtl. Werk., Jubiläums-Ausgabe, hrsg. H. Glockner, Bd. V, S. 351; Enzyklopädie, Einleit., §6: "ein sich in sich selbst schließender Kreis" (Bd. VI, S. 24); Croce, La Poesia, 5a ed., p. 29: "Ma l'azione, giunta a compimento, si rivolge su sé stessa, par che torni indietro, si rifà sentimento, e col sentimento ricomincia un nuovo ciclo, costante nel suo ritmo già segnato, eppure crecente su sé stesso con incessante arricchimento e perfezionamento.... È singolare che, mentre si accetta e si celebra insigne scoperta la 'circulatio sanguinis' nell'organismo fisiologico, si ri lutti all'idea della circolarità spirituale, che... da un grande filosofo italiano venne elevata e principio di spiegazione dello spirito e della storia come 'corso' e 'ricorso'"【參觀 , June 1961, pp. 174-5】又 Filosofia, Poesia, Storia, pp. 71 ff. 論 "se la vita dello spirito sia da considerare sotto il simbolo della 'cuspide' o sotto quello del 'circolo'" 亦論此而無此明暢); Schelling 論 "die Kreis-linie" (見 E.D. Hirsch, Jr., Wordsworth & Schelling, p. 70 引 又第七五○則。【Ronsard: "Hymne du Ciel": "[l'esprit de 1'Éternel] De tous côtés t'anime et donne mouvement, / Te faisant tournoyer en sphere rondement, / Pour être plus parfait; car en la forme ronde. / Gît la perfection qui toute en soi abonde / ... De toi-même tout rond, comme chose éternelle, / Tu n'as en ta grandeur commencement, ni bout" etc. (p. 34); Coleridge's letter to Joseph Cottle: "The common end of all narrative, nay, of all Poems is to convert a series into a Whole: to make those events, which in real or imagined History move on in a strait Line, assume to our Understandings a circular motion— the snake with it's Tail in it's Mouth" (Collected Letters, ed. E.L. Griggs, III, p. 545). 又六百九十九則論 The Pentamerone, p. 422.】【《莊子‧寓言篇第二十七》:"始卒若環,莫得其倫,是謂天均";《孫子‧勢篇》:"渾渾沌沌,形圓而不可敗也。"】【Hugo, Littérature & Philosophie Mêlées, ed. Albin Michel, p. 241: "Le cercle, symbole mystérieux, éternité et zéro, tout et rien."F. Schlegel,Literary Notebooks, ed. H. Eichner, §566 (p. 70): "Alle Bildung und Poesie ist cynlisch. Die alte cyklisirt, die moderne cyklisirend" (cf. §578, p. 68: "Der Gang der modernen Poesie muss cyklisch d.h. cyklisirend sein, wie der die philosophie").

Enn., IV. ii. 18: "Quant au langage, on ne doit pas estimer que les âmes s'en servent, en tant qu'elles sont dans le monde intelligible.... chacun est comme un oeil; rien de caché ni de simulé; en voyant quelqu'un, on connaît sa pensée avant qu'il ait parlé" (IV, p. 85); IV. ix. 5: "Dans le monde intelligible, toutest transparent" (IV, p. 235). 按參觀 Karl Vossler, The Spirit of Language in Civilization, tr. Oscar Oeser, p. 32: "When Dante wrote the Paradiso, he realized that here no language could be adequate. The angels & the blessed light."

, V. iii. 17: "un contact intellectuel" etc. (V, p. 73). Cf. Eckhart, Sermon, XVI & XXIV on "the soul receiving a kiss from the Godhead" & "the kiss exchanged between the unity of God & the humble man" (James M. Clark, Meister Eckhart, pp. 203, 242).

Xenophon, Oeconomicus, viii. 19 ("The Loeb Classical Library", tr. E.C. Marchant, p. 437): "Yes, no serious man will smile when I claim that there is beauty in the order even of pots & pans set out in neat array, however much it may move the laughter of a wit." T.R. Glover, Greek Byways, p. 159譯為:"The wit might laugh, but no serious person, when I say that there is a rhythm (εὔρυθμον) even in pots marshalled in order",精彩始出。John Dewey, Art as Experience, pp. 175 ff. 論空間藝術亦有"韻節",至曰:"The separation of rhythm & symmetry & the division of the arts into temporal & spatial... is based on a principle that is... destructive of esthetic understanding" (p. 183); 又 T.M. Greene, The Arts & the Art of Criticism, p. 220: "strictly speaking, natural rhythm characterizes only temporal events. But the time factor may be introduced by the observer in the process of passing a number of static objects successively in review and in noting recurrent similarities & differences",不知數千年前早有人拈,而作美學史者,無不錯過。參觀 Leonardo da Vinci 論畫與樂通 (R.J. Clements, Michelangelo's Theory of Art, p. 53); 又 Wordsworth: "Airey-Force Valley": "... how sensitive / Is the light ash! that, pendent from the brow / Of yon dim cave, in seeming silence makes / A soft eye-music of slow-waving boughs." 參觀百十一則論 Jaeger, Paideia, I, . 125-6.【A. Lalande, Vocabulaire technique et critique de la philosophie, 7eéd., p. 935 引 L. Boisse: "... le rythme est l'âme de la durée."

六百八十三

E.H. Warmington, Remains of Old Latin (The Loeb Classical Library). 頗有璣羽可拾。Ennius 與 Lucilius 尤所謂句重語奇者也。

Ennius, Annals, fr. 141-2: "Vulturus in silvis miserum mandebat homonem. / Heu! Quam crudeli condebat membra sepulchro!"(vol. I, p. 50). 按可補第一百六十七則論 The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, I, . 69

Annals, fr. 352: "et simul erubuit ceu lacte et purpura mixta"(vol. I, p. 128). 按衹似德國成語所謂 "wie Milch und Blut",或意語所謂 "Essere sangue e latte" Propertius, II. iii. 12: "utque rosae puro lacte natant folia." Antoine de Baïf, Amours de Méline, II. 5: "Cette délicate joüe / En son vermeil verdelet, / Semble une rose qui noüe / Sur un blanc etan de lait" (H. Weber, La Création poétique au 16e siecle en France, I, 267 尤後來居上,氷寒於水矣。【Giles Fletcher: "His cheeks as snowy apples sopped in wine, / Had their red roses quenched with lilies white, / And like to garden strawberries did shine / Washed in a bowl of milk."

Annals, fr. 499-500: "Quomque caput caderet, carmen tuba sola peregit et pereunte uiro raucus sonus aere cucurrit" (vol. I, p. 186), 注引 Statius, Thebaid, XI. 56: "iam gelida ora tacent; carmen tuba sola peregit" 為比。按參觀 Ariosto, Orlando Furioso, XXIX. 26: "Quel fe' tre balzi; e funne udita chiara voce, ch'uscendo nominò Zerbino" ("Biblioteca classica Hoepliana", p. 315),蓋皆本之 Iliad, X. 10。其他如 Ovid, Metam., V. 104; Spenser, Faerie Queene, IV. viii 紛紛祖構,要以Ennius, Statius, Ariosto 三家為妙。Orl. Fur., XLII. 14 (p. 447): "[Brandimarte dying] E dirgli: 'Orlando, fa che ti raccordi / Di me ne l'orazion tue grate a Dio; / Né men ti raccomando la mia Fiordi...' / Ma dir non poté: 'ligi', e qui finio";又XV. 84 (p. 144): "Immantinente al suo destrier [Orrilo] ricorse, / Sopra vi sale, e di seguir non resta; /Volea gridare: Aspetta, volta, volta! / Ma gli avea il duca già la bocca tolta" 可參觀,文心幻變,筆舌玲瓏,得未曾有。又按 Silius Italicus, Punica, IV, 378-9 寫獅鬥云:"脛爪已膏齒牙,尚肆搏擊"(illi dira fremunt, perfractaque in ore cruento ossa sonant, pugnantque feris sub dentibus artus) ("The Loeb Class. Lib.", I, 196),思致略同。Cf. Shakespeare, I Henry IV, V. iv (& my marginalia to Complete Works, ed. G.L. Kittredge, p. 578).

Ennius, Satires, fr. 12-3: "caepe maestum"(I, p. 386). Naevius, Comedies, fr. 20: "Cui caepe edundod oculus alter profluit" (II, p. 80); Lucilius, Satires, fr. 216: "flebile caepe simul, lacryniosaeque ordine tallae" (III, p. 66); fr, 218: "lippus edenda acri assiduo ceparius cepa" (III, p. 68) 皆可參觀。以雪涕而曰傷心 (maestus, flebilis),刻劃洋蔥可謂曲善體會矣。明人汪廷訥《獅吼》第廿一折云:"婦人手如乾薑,定配侯王。我娘子手不是薑,怎麽半月前打的耳巴,至今猶辣?"Antony & Cleopatra, I. ii: "indeed the tears live in an onion that should water this sorrow"; Beauty & the Beast: "These wicked creatures rubbed their eyes with an onion to force some tears when they parted with their sister" (I. & P. Opie, The Classic Fairy Tales, Granada, 1980, p. 187).

Caecilius, fr. 130-1: "limassis caput" (I, p. 514). 按 Livius Andronicus, Tragedies, fr. 25-6: "limavit caput" [19] (II, p. 12) 皆言接唇也。今法國俚語以 "limer" 字為兩具交接,參觀第五百八則。

Naevius, Comedies, fr. 74-9: "Quasi pila / in choro ludens datatim dat se et communem facit. / Alii adnutat, alii adnictat, alium amat alium tenet. / Alibi manus est occupata, alii pervellit pedem; / anulum dat alii spectandum, a labris alium invocat, / cum alio cantat, at tamen alii suo dat digito litteras"(II, pp. 98-100). 按活畫出勾蜂引蝶、多多益善之風騷婦人,遠勝於 The Celestina, tr. L.B. Simpson, p. 88一節,而尚不如 Camille Desmoulins 語,詳見第六百三十一則眉。Gottfried Keller Die Leute von Seldwyla "Die drei gerechten Kammmacher" 一篇寫一女使求婚者三人相安無事,喻曰:"So gibt es Virtuosen, welche viele Instrumente zugleich spielen, auf dem Kopfe ein Glockenspiel schütteln, mit dem Munde die Panspfeife blasen, mit den Händen die Gitarre spielen, mit den Knieen die Zimbel schlagen, mit dem Fuss den Dreiangel und mit den Ellbogen eine Trommel, die ihnen auf dem Rücken hängt" (Sämtl. Werk., Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag, 1958, Bd. VI, S. 237) La Celestina, VII: "que uno en la cama y otro en la puerta, y otro que suspira por ella en su casa, se precia de tener... y a todos muestra buena cara, y todos piensan que son muy queridos. Y cada uno piensa que no hay otro" (Éd. Aubier par P. Heugas, "Collection Bilingue des Classiques Étrangers", p. 292).】【陳曇《鄺齋雜記》卷五:"鑼鼓三,譚姓,開平人,其技以手肘鳴鑼,以足趾搥鼓,以口吹竹,以手彈絲。又能一足擊鼓,一足鳴鈸,口吹喇叭。蓋合鼓吹一部,集眾人之能而身兼之。"慵訥居士《咫聞錄》眷一:"談三,開平人,瞽目。……身坐席上,先吹打一會,口吹鎻,肘敲大囉,右足撞鋍,順擊教鑼,左足敲鼓搖板。"】

Naevius, Unassigned Fragments, fr. 7-8: "retritum rutabulum"(II, p. 140), "Naevius obscenam viri partem describens." Eric Partridge 未知此,可補 Dict. of Slang, 4th ed., p. 645 "poker", "burn one's poker"; p. 1151 "red hot poker"

Pacuvius, Plays, fr. 47-8: "Nam canis, quando est percussa lapida, non tam illum adpetit. / Qui sese icit, quam illum eumpse lapidem, qui ipsa icta est, petit"(II, p. 178). Orlando Furioso, XXXVII. 78 等實出於此,宜補第五百三十一則。

Lucilius, Satires, fr. 302: "hunc molere, illam autem ut frumentum vannere lumbis" [23] (III, p. 92). 按 fr. 361: "Crisabit ut si frumentum elunibus vannat"(III, p. 112) 體物極妙。 molerePartridge, Dict. of Slang, 4th ed., p. 355: "Grind" James Reeves, The Idiom of the People, p. 156 載英國古民謠 "The Miller & the Lass" "She swore she'd been ground by a score or more / But never been ground so well before." F. Nork, Mythologie der Volkssagen und Volksmärchen, S. 301-2: "In der symbolischen Sprache bedeutet aber Mühle das weibliche Glied (μνλλος, wovon mulier), und der Mann ist der Müller, daher der Satyriker Petronius molere mulierem für: Beischlaf gebraucht. Der durch die Buhlin der Kraft beraubte Samson muss in der Mühle mahlen (Richter XVI. 21.), welche Stelle der Talmud wie folgt eommentirt: Unter dem Mahlen ist immer die Sünde des Beischlafs zu verstehen... Wie Apollo war auch Zeus ein Müller (Lycophron, 435)... insofern er als fchaffendes, Leben gebendes Prinzip der Fortpflanzung der Geschöpfe vorsteht... jede Vermählung eine Vermehlung." F. Sacchetti, Il Trecentonovelle, CCVI, Opere, Rizzoli, pp. 707 ff.: "un poco leggiadro, secondo mugnaio", "considerando al macinare che avea a fare la seguente notte", "hai macinato sette volte" ecc. vannere之喻,他書未見。

Lucilius, Sat., fr. 995-6: "... mercede quae conductae flent alieno in funere praeficae, multo et capillos scindunt et clamant magis"(III, p. 332). 乃知王得臣《麈史》卷下記京師風俗可笑,有云:"家人之寡者,當其送終,即假倩媼婦,使服其服,同哭諸途,聲甚淒惋。仍時自言曰:'非預我事'";《癸巳類稿》卷十三《哭為禮儀說》所云云,古羅馬亦有其俗。【Don Quixote, II, Cap. 7: "al modo de las endechaderas" ("Clásicos Castellanos", V, p. 141, note pp. 141-2); Beaumont & Fletcher,The Maid's Tragedy, V. iv: Calianax: "My daughter dead here too! And you have all fine new tricks to grieve; but I ne'er knew any but direct crying" (Selected Plays, "Everyman's", p. 152).

Lucilius, Sat., fr. 1074: "Sicuti te quem aequae speciem vitae esse putamus"(III, p. 348). 按似指人言。J.W.H. Atkins, Literary Criticism in Antiquity, II, p. 13 "... his work... was allied to comedy, both being mirrors of life",頗穿鑿無據。故 E.R. Curtius 所徵引,亦每近附會,如 S. 483 (dilatatio) (abbreviato) Quintilian Quintilian 此節乃論誇大過情與抑損失實,觀VIII. iv. 1 ("Loeb", III, p. 262) 所舉四例可知也。

Lucilius, Unassigned Fragments, fr. 1182: "Haec inbubinat at contra te inbulbitat ille" [27] (III, p. 384), "Bubinare est menstruo mulicrum sanguine inquinare. Inbulbitare est puerili stercore inquinare." 按前一事,李笠翁《鳳求凰》第六折所謂"猩紅滿褲襠,特來包染硃砂棒"是也;後一事,《山中一夕話》卷二《禁男風告示》所謂"屎蒙麈柄"是也 。《弁而釵》第四風翰林謂趙生曰:"閉其上竅,便無穢物出";《品花寶鑑》第二十三回姬亮軒謂孫嗣徽曰:"瘦寬肥緊麻多糞,如遇糞車,也可坐得,大木耳一個,水泡軟了作帽子,亦即車墊";又第四十回奚十一與得月事,皆可參觀。

六百八十四

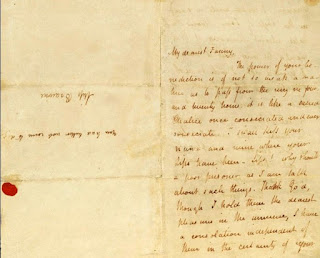

H.E. Rollins, ed., Letters of John Keats.

"I am certain of nothing but of the holiness of the Heart's affections & the truth of Imagination — What the Imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth" (I, p. 184). Cf. "The excellence of every Art is its intensity, capable of making all disagreeables evaporate, from their being in close relationship with Beauty & Truth" (I, p. 192); "I never can feel certain of any truth, but from a clear perception of its Beauty" (II, p. 19). Surely, the famous sententious line in the "Ode on a Grecian Urn" — "Beauty is truth, truth beauty" — means no more than this. These obiter dicta leave us in the dark— and I'm afraid that Keats was not himself very clear on the point, whether the beautiful makes the truth true or merely shows it to be true; in other words, an equivocation similar to the pragmatist attempt to identify the useful with the true. The nature of truth and the test f truth are two problems, not one. The laborious exegeses if many critics (e.g. Kenneth Burke's explanation of Keats's line in dialectical terms in A Grammar of Motives, pp. 447 f.) seem to me quite wide of the mark. That beauty is the shining-forth of truth is a doctrine as old as Plato (cf.Symposium, 211a: "...the beautiful presented to him in the guise of a face or of hands" etc., tr. W.R.M. Lamb, "The Loeb Classical Library", p. 205), cf. Shaftesbury, Characteristics, ed. J.M. Robertson, I, p. 94: "For all beauty is truth"; Fr. Schlegel, Literary Notebooks, ed. Hans Eichner, §124, p. 30: "Das Schöne ist eben so wohl angenehme Erscheinung des Wahren und des Rechtlich-Geselligen als des Guten"; §1818, p. 181: "Das Schöne ist eben zugleich gut und wahr"; & Hegel, Ästhetik, Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag, 1955, S. 145-6: "So ist Schönheit und Wahrheit einerseits dasselbe... Das Schöne bestimmt sich dadurch als das sinnliche Scheinen der Idee." (Aufbau-Verlag, 1955, S. 212).Cf. E. Cassirer, The Philosophy of the Enlightenment, tr. F.C.A. Koelln & J.P. Pettegrove, p. 314 on Shaftesbury's "The truh of the universe speaks, as it were, through the phenomenon of beauty; it is no longer inaccessible, but acquires a means of ex-pression...." Cf. also

On Shakespeare's "negative capability", that is, to be "capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries" etc. (I, p. 193). To Rollins's note should be added the very informative article in Studies in Philology, Jan. 1958, pp. 77 ff., in which similar views of Coleridge, Hazlitt & Shelley are quoted; Lamb held the same view: "He [Wordsworth] does not, like Shakespeare, become everything he pleases, but forces the reader to submit to his individual feelings" (H.C. Robinson, On Books & Their Writers, ed. Edith Morley, I, p. 17); cf. also II, p. 213: "Dilke was a man who cannot feel he has a personal identity unless he has made up his mind about everything. The only means of strengthening one's intellect is to make up one's mind about nothing — to let the mind be a thoroughfare for all thoughts." Flaubert expresses himself also very strongly on this point: "L'ineptie consiste à vouloir conclure" (Correspondance, éd. Louis Conard, II, p. 239); "Aucun grand génie n'a conclu et aucun grand livre ne conclut, parce que l'humanité elle-même est toujours en marche et qu'elle ne conclut pas" (IV, p. 183); "La rage de vouloir conclure est une des manies les plus funestes et les plus stériles qui appartiennent à l'humanité" (V, p. 110). Cf. the German epigram: "Denken ist schwer — darum urteilen die meisten." Cf. 第五百四十四則 第六百九十六則Robert Musil's "Essayismus" & "Möglichkeitssinn" in Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften, Kap. 4, but for the schizoid lengths to which they are pushed, have something in common with "negative capacity". This Letter to Richard Woodhouse has a great influence on Hofmannsthal as he confesses to Stefan Grass in a letter: "Der schöne Brief von Keats... der Brief mit den merkwürdigen Klagen über das Chamäleondasein des Dichters ('he has no identity', etc.). Dieser Brief hat mich sehr entlastet" usw. (Briefe, Bd. II, p. 254; cf. "Gespräch über Gedichte": "Dass sich sein Dasein, für die Dauer eines Atemzugs, in dem fremden Dasein aufgelöst hatte. Das ist die Wurzel aller Poesie" — Gesam. Werke, Frankfurt am Main, Bd. II, Prose, p. 89; "Der Dichter und und diese Zeit": "Es... nimmt seine Farbe von den Dingen, auf denen er ruht" — p. 244).Cf. Baudelaire, quoted towards the end.

"Poetry should be great & unobtrusive, a thing which enters into one's soul, & does not startle it or amaze it with itself, but with its subject — How beautiful are the retired flowers!" etc. (I, p. 224). This is the opposite of Marino's theory of "far stupir" (cf. infra 第七百三則) and an anticipation of T.S. Eliot's view of "poetry which should be essentially poetry, with nothing poetic about it, poetry standing naked in its bare bones, or poetry so transparent that we should not see the poetry, but that which we are meant to see through the poetry" (quoted in F.O. Matthiessen, The Achievement of T.S. Eliot, 2nd ed., 1947, p. 90; cf. R. Johnson's interesting article "Jiménez, Tagore & 'La Poesía Desunda'" in MLR, Oct. 1965, pp. 541-2, where Eliot's passage has been overlooked). Cf. Coleridge, The Notebooks, ed. Kathleen Coburn, II, §2728: "Modern poetry characterized by the Poets ANXIETY to be always striking — The same march in the Greek & Latin Poets/Claudian... observe in him the anxious craving Vanity! every Line, nay, every word stops, looks full in your face, & asks & begs for Praise..." This parallels Keats's remarks: "How they would lose their beauty were they to throng into the highway crying out, 'Admire me, I am a violet! Dote upon me I am a primrose!'" Cf. Wordsworth's sonnet "Not Love, not War": "The flower of sweetest smell is shy and lowly."

"It is a great Pity that People should by associating themselves with the finest things, spoil them — Hunt has damned Hampstead & Masks & Sonnets & Italian tales — Wordsworth has damned the lakes... Peacock has damned satire"(I, p. 252); II, p. 11: "Hunt does one harm by making fine things pretty, & beautiful things hateful — Through him I am indifferent to Mozart." How profoundly true — especially in political causes: Lamennais: "Les républicains sont fait pour rendre la république impossible"; New Statesman, 22 March 1958, p. 387: "Rien n'ébianle plus nos croyances que le spectacle de ceux qui les partagent: le plus grand obstacle à la propagation du communisme, c'est [sic.] les communistes mêmes [sic.]." Cf. 第一百八十二則 第六百六十二則Cf. Coleridge to John Thelwall: "It is not his Atheism that has prejudiced me against Godwin, but Godwin who has, perhaps, prejudiced me against Atheism" (Collected Letters, ed. E.L. Griggs, I, p. 221).】【Veronica Hull, The Monkey Puzzle, p. 189: "The trouble with revolution is one's co-revolutionaries."】【Yossarian in Joseph Heller's bitterly hilarious novelCatch-22, p. 435 says: "Between me and every ideal I always find Scheisskopfs, Peckems, Korns & Cathcarts. And that sort of changes the ideal."】【F. Rolfe, Hadrian the Seventh, "The Phoenix Library", p. 23: "As for the Faith, I found it comfortable. As for the Faithful, I found them intolerable." Cardinal de Retz: "L'on a plus de peine, dans les partis, à vivre avec ceux qui en sont qu'à agir contre ceux qui y sont opposés" (Gaëtan Picon, L'usage de la Lecture, p. 29).[31]Alphonse Daudet: "O politique, je te hais. Tu sépares de braves coeurs faits pour être unis; tu lies au contraire des êtres tout à fait dissemblables" (A. Albalat, Souvenirs de la vie littéraire, nouv. éd., p. 10). Paul Léautaud,Journal Littéraire, II, p. 190 on Rémy de Goncourt: "Son emballement tardif jour Stendhal a dégoûtéValéry. 'J'ai renoncé a lire Stendhal depuis ce jours-là.'"】【Yeats to T. Sturge Moore: "When a man is so outrageously in the wrong as Shaw he is indispensible [the Academic Committee of English Letters], if it were for no other purpose than to fight people like Hewlett, who corrupt the truth by believing in it" (Ursula Bridge, W.B. Yeats & T. Sturge Moore: Their Correspondence, p. 19).】【Emerson: "Yes, they adopt whatever merit is in good repute, & almost make it hateful with their praise"(Emerson: A Modern Anthology, ed. A Kazin & D. Aaron, p. 175). Through inflation, the currency is depreciated.

"... for axioms in philosophy are not axioms until they are proved upon our pulses: We read fine things but never feel them to the full until we have gone the same steps as the Author... no man can set down Venery as a bestial or joyless thing until he is sick of it & therefore all philosophizing on it would be mere wording"(I, p. 279); cf. II, p. 81: "Nothing ever becomes real till it is experienced — Even a Proverb is no proverb to you till your life has illustrated it." Cf. 第五則 à propos of a remark of Saint-Évremond & 第一百四十一則 à propos of a remark of Kierkegaard.

"The Duchess of Dunghill" (p. 321). Cf. Proust, Sodome & Gomorrhe, II, ch. 3 (À la recherche du temps perdu, Bib. d. l. Pléiade, II, p. 1090): "Que vous di alliez faire pipi chez la comtesse Caca, ou caca chez la baronne Pipi, c'est la même chose." Cf. "La Contessa di civillari" & "Don Meta" in Il Decameron, VIII. 9 (ed. Hoepli, p. 532); M. Bandello, Le Novelle, I. 35: "il tributo... a la contessa di Laterino" (Laterza, II, p. 53).【Moss Hart & George S. Kaufman, The Man Who Came to Dinner: "Lord Bottomley" & "Lady Fanny" (16 Famous American Plays, "Modern Lib.", p. 865).】【又下頁 E. Partridge, Dict. of Slang, p. 665: "the Countess (Duchess) of Puddledock."】【Swinburne's La Soeur de La Reine (in Cecil Y. Lang , ed., New Writings by Swinburne, 1965), Act. II, sc. Iv, an usher announces: "Milady duchesse de Fuckingstone... miss Sarah Butterbottom... milady marquise de Mausprick... milord Shittingbags... milady Cunter" etc.

"A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence; because he has no Identity; he is continually filling some other Body" etc. (I, p. 387, cf. supra I, 193).Cf. Baudelaire: "Les Foules": "Le poète jouit de cet incomparable privilège, qu'il peut à sa guise être lui-même et autrui. Comme ces âmes errantes qui cherchent un corps, il entre, quand il veut, dans le personnage de chacun. Pour lui seul, tout est vacant" etc. (Petits Poèmes en Prose, Oeuv. Comp., Bib. d. l. Pléiade, p. 95).

The Masterly analysis of the occupational schizophrenia of the parson (II, p. 63) beginning with "A Parson is a lamb in a drawing room & a lion in a vestry." Rollins in the footnote quotes the English proverb "A lamb in the house & a lion in the field"; cf. James Joyce, Ulysses, p. 452: "Street angel & house devil" & the French adage "Lion au logis, renard dans la plaine", or the German one "Hausteufel, Gassenengel."【Epictetus, Discourses, IV. v: "The proverb about the Lacedaemonians, 'Lions at home, but at Ephesus foxes,' will fit us too: lions in the schoolroom, foxes outside" ("The Loeb Class. Lib.", II, p. 345); Nicholas Breton: "A Sweet Lullaby": "Although a lion in the field, / A lamb in town thou shalt him find."】

On claret: "then you do not feel it quarrelling with your liver — no it is rather a Peace maker & lies as quiet as it did in the grape" (II, p. 64). Cf. Rilke, From the Remains of Count C.W., II. x: "Im Halse des Erstickten ist die Gräte so einig mit sich selber wie im Fisch."

"Our bodies every seven years are completely fresh-materialed... we are like the relic garments of a saint, the same & not the same" etc. (II, p. 208). Cf. Jane Austen's Letters, ed. R.W. Chapman, 2nd ed., p. 148: "But seven years I suppose are enough to change every pore of one's skin, & every feeling of one's mind." Also《列子‧天瑞篇》:"損盈成虧,隨世隨死。往來相接,間不可省,疇覺之哉?亦如人自世至老,貌色智態,亡日不異;皮膚爪髮,隨世隨落。" Jean-Baptiste Chassignet: "Mais tu ne verras rien de cette onde première / Qui naguère coulait; l'eau change tous les jours, / Tous les jours elle passe, et la nommons toujours / Mesme fleuve, et mesme eau, d'une mesme manière. // Ainsi l'homme varie, et ne sera demain / Telle comme aujourd'hui du pauvre corps humain / La force que le temps abrévie et consomme: / Le nom sans varier nous suit jusqu'au trépas."《肇論‧物不遷論第一》:"人則謂少壯同體,百齡一質,徒知年往,不覺形隨。是以梵志出家,白首而歸。鄰人見之曰:'昔人尚存乎?'梵志曰:'吾猶昔人,非昔人也。'鄰人皆愕然"( 柳宗元《戲題石門長老東軒》:"坐來念念非昔人");劉勰《新論‧惜時篇》:"夫停燈於缸,先驗焰非後焰,而明者不能見;藏山於澤,今形非昨形 ,而智者不能知。" Cf. Spinoza, Ethics, Pt. IV, Prop. 38, Schol. (Selections by J. Wild, p. 327) on the body which dies but does not become a corpse. Cf. Francisco de Quevedo's Sueños: "Vous êtes tous les morts (muertes) des vous-mêmes... Ce que vous appelez vivre; c'est mourir en vivant (morir viviendo)" (J. Rousset, La Littérature de l'âge baroque en France, p. 117); & his sonnet "¡Ah de la vida!": "Ayer se fue; mañana no ha llegado; / Hoy se está yendo sin parar un punto: / soy un fue, y un será, y un es cansado. / En el hoy y mañana y ayer, junto / pañales y mortaja, y he quedado / presentes sucesiones de difunto" (Eleanor Turnbull, Ten Centuries of Spanish Poetry, p. 308); Hugo von Hofmannsthal: "Terzinen über Vergänglichkeit": "Und dass mein eignes Ich, durch nichts gehemmt, / Herüberglitt aus einem kleinen Kind / Mir wie ein Hund unheimlich stumm und fremd. / Dann: dass ich auch vor hundert Jahren war // Und meine Ahnen, die im Totenhemd, / Mit mir verwandt sind wie mein eignes Haar // So eins mit mir als wie mein eignes Haar" (Leonard Forster, The Penguin Book of German Verse, p. 395). Cf. Hume, Treatise, Bk. I, Pt. iv, Sct. 6: "Of Personal Identity" (ed. L.A. Selby-Bigge, I, pp. 251 ff.): "If any impression gives rise to the idea of self, that impression must continue invariably the same, through the whole course of our lives... But there is no impression constant & invariable. Pain and (p. 251) pleasure, grief & joy, passions & sensations succeed each other, & never all exist at the same time... when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure (p. 252)... The mind is a kind of theatre... There is properly no simplicity in it at one time, nor identity in different" (p. 253). Cf. 七六六則 on André Gide. George Herbert: "Giddinesse" [35]: "Oh what a thing is man! how farre from power, / From settled peace & rest! / He is some twentie sev'rall men at least / Each sev'rall houre" (Works, ed. E.F. Hutchinson, p. 127); J.-B. Chassignet [36], Mépris de la vie, sonnet v: "Le nom sans varier nous suit jusqu'au trépas, / Et combien qu'aujourd'hui celui ne sois-je pas / Qui vivais hier passé, toujours même on me nomme" (J. Rousset, Anthologie poesie baroque fr., p. 199); L. Pirandello, Uno, Nessuno e Centomila, Lib. II, cap. 5: "Riconoscete forse anche voi ora, che un minuto fa voi eravate un altro... non solo, ma voi eravate anche cento altri, centomila altri... Vedete piuttosto se vi sembra di poter essere cosí sicuro che di qui a domani sarete quel che assumete di essere oggi" (Opere, II, Tutti i Romanzi, a cura di C. Alvardo, p. 1310).

"And in latin there is a fund of curious literature of the middle ages" (II, p. 212). Though Keats here writes out of hearsay, his interest in mediaeval Latin should have earned him a tribute from Remy de Gourmont (cf. Le Latin mystique, p. 19 on the attitude of les cuistes scandalisés towards le latin d'église) & E.R. Curtius (cf. Europäische Literatur und lateinisches Mittelalter, 2te Aufl., S. 22-3).

On the Paradise Lost as "a corruption of our language" with a baneful seductiveness "against" which he "stood on guard" (II, p. 212). I think this is the germ of T.S. Eliot's famous "Milton I" (On Poetry & Poets, pp. 138 ff.) on the "bad influence" of Milton's "rhetorical style". (J.M. Murry quoted Keats's remark in his attack on the Miltonic style, cf. L.P. Smith, Milton & His Modern Critics, p. 19.) In his scathing criticism of Eliot's palinode with regard to Milton (RES, May 1959, p. 212), James Sutherland has failed to see that Eliot took his cue from Keats.

In a footnote on II, p. 263, Rollins quotes Fanny Brawne's letter to Brown on Dec. 29, 1829: "I fear the kindest act would be to let him [Keats] rest for ever in the obscurity to which unhappy circumstances have condemned him. Will the writings that remain of his rescue him from it?" So this is her honest, well-considered opinion of the achievement of her lover, a man "who [she] had often heard called the best judge of poetry living" (F, Edgecumbe, ed.,

Letters of Fanny Brawne to Fanny Keats, p. 63). My high opinion of the woman, formed after reading her letters to Keats's sister, has come down with a resounding bump.

六百八十五

《西青散記》敘事狀物,峭折而不塞澀,學竟陵每有出藍之嘆。好作勸善語,卷一十二月六日稱引《文昌惜字訓》,卷二記胡達湖道《太上感應篇》(參觀《華陽散稿》卷下《文昌清錄序》),蓋其著眼所在,欲以情趣、事趣兼道學、理學者也。(《華陽散稿自序》皆言"趣",卷下《竹谿曹隱君傳》記其論《西青散記》曰:"此勸善之書";《冷廬雜識》卷一稱此書"諷世之語,隽而不腐。")《散記》卷二記儲證園語云 :"風流近優,儒雅近腐,此非佳人之鐵圍山耶?"第一句固未然,第二句正自不免。所載詩遠遜詞,四言及五、七古尤瘖吃不成語。余《談藝錄》三○五頁 ,又一百三十則所標舉外,卷四梧岡自記赴試道中七律有云:"野水風摩微皺活,暮山雲抹小尖平",差有致。又卷二載張夢覘《瘞落花》絕句云:"夕陽庭院春濃夜,黃透胭脂病已來",尚見心思,正可與卷三雙卿《和白羅詩九首》所謂"苦黃生面喜紅消"參勘耳。梧岡詞筆亦在詩上,如卷二《惜餘春》、《蝶戀花》二闋,皆讀之使人惘惘不甘。于辛伯《燈窗瑣話》卷四所稱"記得深深深夜語,生生死死千千句"(謂與汪端光─《無題》"並無歧路傷離別,正是華年算死生"皆描摹兒女心口曲肖【洪亮吉、張船山集中皆及汪氏】),即《蝶戀花》結句也(《華陽散稿》卷下《小鳳別紀》載《免鬚詞》亦佳)。餘見第一百二十四則、第一百七十七則。【程魚門《勉行堂集》多可與梧岡《散稿》參證:《詩集》卷一《邊葦間所藏合璧硯余偶得之為作長歌》、卷二《和史廣文悟岡懷隱三首》、《懷人詩十八首‧第三‧史震林公度》、《第十七‧山陽周振采白民》、卷四《和史梧岡無題三首》、《仲夏同史梧岡邊葦間周白民等集晚甘園》、卷六《偶過東城懷邊葦間成七絕句》、卷十三《途次懷人詩十二首‧第三‧史廣文梧岡》、《文集》卷三《淮陰蘆屋記》(邊壽民)。段若膺《經韻樓集》卷九《蔡一帆先生傳》謂其"詩集不傳,今惟於史悟岡丈《西青散記》得《句容唐潘王三烈婦詩》。"】【清季俗書程麟趾《此中人語》卷三《悟岡老人詩詞記》:"悟岡有《書畫同珍》二卷。"

〇《西青散記》卷一清華君下壇詩云:"琅玕消息近來聞,玉冷空山墮小雲。滄海西頭裙自浣,翠微深處被親薰。人離月殿分鸞守,草滿芝田赴鶴芸。香篆若能通御座,萬枝真降一齊焚。"按楊掌生《夢華瑣簿》記何芰亭獲盜,贜中有竹簡,上刻乩仙七律,謂"似玉溪生《錦瑟》、《碧城》之作",即此詩,不知其出《散記》也。

〇《西青散記》卷一載玉勾詞客吳震山婦安定君詩云 :"日日薰香禮覺王,不任操杵不縫裳。誰言鹿苑無生訣,未及龍宮不死方。"按《列朝詩集》丁六屠長卿《游仙》云:"一緉芒鞋四海忙,何如回首覓靈光。為言鹿苑無生訣,即是龍宮不死方。"才婦乃作賊耶?《散記》冠以玉勾詞客一《序》,嘗檢曹震亭《香雪文鈔》卷有《西青散記序》,悟岡不取以弁首,未識何故?

〇《華陽散稿自序》云:"做無趣之夢,串無趣之戲,豈不負有趣之天,虛有趣之地乎哉?搭不三不四之人,作不深不淺之揖,喫不冷不熱之餅,說不痛不癢之話,小人之描畫君子,雖為無禮,不為無趣也。"按劉同人《帝京景物略》卷四《首善書院》條云:"御史倪文煥等詆鄒元標、馮從吾二先生為偽學,有疏曰:'聚不三不四之人,說不痛不癢之話,作不深不淺之揖,啖不冷不熱之餅'(《蒿菴閒話》卷一記此數語,據同卷"利瑪竇"、"元君"兩則,則取之《景物略》也;《茶餘客話》卷九引此數語,據卷十五引"史公度震林《劄記》"金沙人奇吝事,則本之《散記》矣)",悟岡疑逕取諸《景物略》。【朱竹垞《明詩綜》卷七十一馮元颷《首善書院感舊作》(七古長篇)後詩話亦詳記此事 ,且云:"崇禎初,文煥伏法。宮保[徐光啟]率[湯]若望等借院修曆,署曰'曆局'。久之,西洋人踞其中,更為天主堂,至今不改矣。 "】劉、于之書,筆致力求幽隽,竟陵派中一大著作。悟岡所見,必紀曉嵐未刪之原本。生平為文,倘亦得力於此耶?蒲留仙《聊齋文集》卷三《帝京景物選略小引》亦極賞劉、于文之"無讀不峭,無折不幽",為削繁棄贅,是於紀書外又一節本也。留仙文如《逸老園記》、《龍泉橋碑記》(卷二)、《募建龍王廟序》(卷三)亦刻意仿之。【《譚友夏合集》卷七《答劉同人書》;《書影》卷五載王敬哉作《于司直傳》;又顧夢游作于遺詩《序》;吳景旭《歷代詩話》卷四十五、五十一、七十三、八十引《帝京景物略》,紀氏刪本所無;順治八年刻《倪文正公遺稿》卷二《遊西山》,唐九經評云:"詩已刻劉同人《帝京景物略》之中所錄佳句"云云,亦紀本所刪略也;程穆衡《據梧齋詩集》卷三《游右安門外中頂即事成長句》:"糍糰虎鬚草橋市",自注:"《帝京景物略》";《錢湘靈先生詩集抄本》第六冊《閒思》七律稱劉同人文筆,又記其臨歿自見生魂事;杜濬《變雅堂詩集》(汪燊刻本)卷一《吳門追憶昔命袁中郎先生及受命未及任之劉同人兼書所慨》;李世熊《寒支初集》卷二《閱帝京景物略》二首。】

【呂洞賓《題詩紫極宮》云:"宮門一閑人,臨水憑欄立。無人知我來,朱頂鶴聲急。"此《散記》諸詩句樣也。】

"卷十七"前脫"《曝書亭集》"四字,"雨裏"原作"雨外"。

"徐學謨"原脫"學"字,"歸有園麈談"原作"太室麈談"。

後皆收入補訂本《談藝錄》(香港中華書局 頁以下;北京三聯書局 年補訂重排版 頁以下)。

見《錢鍾書英文文集》(北京:外語教學與研究出版社,)350-367 Philoiblon (《書林季刊》), I (1947), pp. 17-26。

Warmington 英譯(下引Remains of Old Latin 同):"A vulture did craunch the poor man in the forest. / Ah! In what a cruel tomb buried he his limbs!"

"And she blushed withal like milk and crimson mingled."

"And when his head was falling, the trumpet finished alone its tune; and even as the warrior did perish, a hoarse blare sped from the brass."

Barbara Reynold 英譯 (下引 Orlando Furioso 同): "These words he uttered just before the end; / 'Remember me, Orlando, when you pray'; / And he continued, 'To you I commend / My Fiordi...' but the 'ligi' could not say."

"He flung himself as quickly as he could / Upon the saddle of his thoroughbred. / He would have liked to shout 'Come back! Come back!' / But of his mouth he felt a grievous lack."

"As though she were playing at ball, give-and-take in a ring, she makes herself common property to all men. To one she nods, at another she winks; one she caresses, another embraces. Now elsewhere a hand is kept busy; now she jerks another's foot. To one she gives her ring to look at, to another her lips blow a kiss that invites. She sings a song with one; but waves a message for another with her finger."

"For when a dog is struck by a stone, it attacks not so much him who strikes it as that same stone by which it was struck."

"That he grinds, but she winnows out as it were corn with her loins."

"She'll jerk as though she were winnowing corn with her buttocks."

"... keeners, who, hired on pay, weep in another's funeral-crowd, tear their hair and cry out much more than others do."

"Just as you, whom we believe to be the very-likeness of the righteous life."

"She stains you, but on the other hand he soils you."

引文當即第四百十六則所補"云云略而未詳者(見《手稿集》 頁夾縫),英譯:"In a party it is more difficult to agree with those who belong to it, than to act against those who are opposed to it."

引文已見第四百六十六則,惟頁數有異。英譯:"O politics, how I hate you! You separate honest hearts which were made to be united. And on the contrary you knit together individuals who are in every respect unlike each other."

J.-B. ChassignetJ.-P. Chassignet

《談藝錄‧三》:"史震林《華陽散稿》卷上《記天荒〉有曰:'當境厭境,離境羨境',參觀卷下《與趙闇叔書〉。尤肅括可亂釋典楮葉矣"(香港中華書局 頁;北京三聯書局 年補訂重排版

按此有誤。"悟岡老人"、"《書畫同珍》"云云,當指鄒梧岡(聖脈)言。