Guattari and Autonomia

In 1974, I was in compulsory military service, living in an Italian army barracks. But military life was not my cup of tea and I was looking for a way out. A friend suggested I read a French philosopher. And so, I began to read Félix Guattari.

I started with his Psychoanalysis and Transversality and drew inspiration for choregraphing a fit of madness. The colonel of the psychiatric clinic deemed I was indeed crazy and they sent me home. From that moment on, I considered Guattari a friend whose work can suggest paths of escape from any type of barracks, physical or otherwise.

Lotta Continua (English: Continuous Struggle) was a far-left militant organization in Italy active during the historical period of social turmoil and political violence in the country known as the “Years of Lead.” License: Public domain.

Lotta Continua (English: Continuous Struggle) was a far-left militant organization in Italy active during the historical period of social turmoil and political violence in the country known as the “Years of Lead.” License: Public domain.

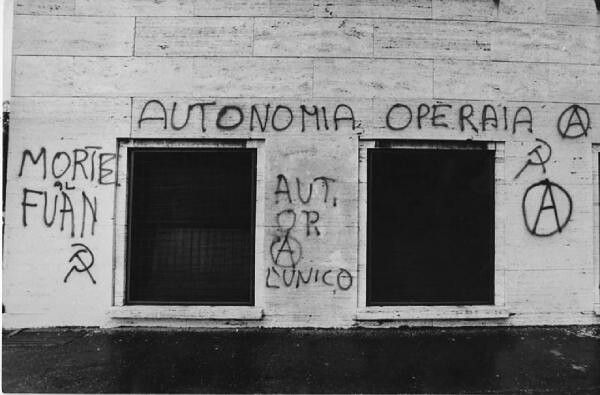

I continued those studies throughout the seventies, when a movement comprised of students and young workers called Autonomia emerged from universities, factories, and occupations. This movement was expressed through many different types of action and organization, including countercultural and aesthetics projects.1 In 1975, I published the first issue of A/traverso, a journal that sought to translate “schizoanalytic” concepts into the language of Autonomia. Then, in 1976, with a group of friends, I launched the first free Italian radio station, Radio Alice. Eventually the police closed the radio station, accusing us of organizing the riots that followed the assassination of Francesco Lorusso, a militant from the extra-parliamentary group Lotta Continua.2

To define itself, the 1977 Bologna movement chose the slogan “desiring autonomy.” Sometimes the expression “we, the transversalists” was used. The reference to post-structuralism was explicit in public declarations, in leaflets, in the watchwords of the spring 1977 demonstrations, in the face of state violence and mass repression.

We had read Anti-Oedipus but hadn’t understood much of it. However, one word had hit us hard: “desire.” We had clearly understood that the driving force of the process of subjectivation is desire. In other words, we proposed: let’s stop thinking in terms of “subject,” let’s forget Hegel (or spit on him, as Carla Lonzi’s 1970 essay is titled).3 In other words, subjectivity is not something ready-made that we have to simply organize. We came to see that there are no subjects, but rather flows of desire traversing organisms that are at the same time biological, social, and sexual—and conscious of course. But consciousness is not something pure and indeterminate. Consciousness does not exist without the incessant work of the unconscious, of that laboratory which is not a theater where one plays out a tragedy already written, but a tragedy traversed by flows of desire that one writes and rewrites nonstop.

Moreover, the concept of desire should not be reduced to an always positive tension: desire is key for explaining the waves of social solidarity and those of aggressiveness, the explosions of rage and the hardening of identity. Both revolutionary libertarian movements and repressive reactions to them are rooted in fluctuations of desire.

Finally, desire is not a happy good boy. On the contrary, it can curl up, it can withdraw into itself and finally produce effects of violence, destruction, barbarism. Desire is the factor of intensity in the relationship with the other. Intensity can go in different directions, even contradictory ways indeed.

Guattari coined the expression retournelles (refrains) in order to define the semiotic concatenations capable of being in a harmonic relationship with the wider environment. The refrain is a vibration whose intensity can be linked with this or that system of signs and nervous stimulations. Desire is the perception of a refrain that we produce to capture the lines of stimulation coming from the other (a body, a word, an image, a situation) to then relate to these lines. Similarly, the wasp and the orchid, two entities having little to do with each other, can nevertheless network, enjoy each other, and produce beneficial effects for each other. Desire is not a natural fact, but an intensity that changes according to anthropological, technological, and social conditions.

Toward a Reconfiguration of Desire

We must reconsider desire in our age that is defined by neoliberal and digital acceleration. We must also reconsider desire in the context of contemporary identitarian reactionary movements.

Neoliberal economics has accelerated the pace of labor exploitation, especially cognitive labor; connective digital technology has accelerated the circulation of information and consequently intensified the rhythm of semiotic stimulation which is, at the same time, nervous stimulation. This double acceleration is the origin and the cause of the increase in labor productivity which has in turn allowed an unprecedented increase in the accumulation of capital. But it is also the cause of the hyper-exploitation of the human organism, especially the brain. Today we have the task of determining the effects that this hyper-exploitation has produced on the psychic balance and on the sensitivity of human beings—as individuals, but above all as a collective.

We must reflect on the mutation of desire following the trauma of the pandemic. The virus may be less visible, the infection may be somewhat under control, but the trauma doesn’t go away overnight; it continues to do its job, which manifests in part as a kind of mass phobic sensitization to the body of the other, their skin, their lips.

During the last two decades, several studies have shown that sexuality is changing in a profound way, and the recent viral shock has only reinforced this trend, which has its roots in a techno-anthropological transformation that dates back thirty years at least. For example, in the 2017 book iGen, Jean Twenge analyzes the relationship between connective technology and the change in the psychological and affective behavior of generations who have been formed in a techno-cognitive environment.4 Following such studies, I have taken to defining the human beings born since the beginning of the century as the generation that has learned more words from a machine than from the singular voice of a human being.

In my opinion, this definition is useful for understanding the depth of the changes underway. Freud introduced the notion that access to language is not understandable without considering the affective dimension. We should also remember what Giorgio Agamben argues in the book Language and Death: the voice is the meeting point between flesh and meaning, body and signification. Moreover, the Italian feminist philosopher Luisa Muraro affirms that the apprehension of the meaning of words is linked with affective confidence in the mother.5

I believe a word means what it means because my mother told me so. More generally, I believe that the world is meaningful because my mother told me that words signify the world. The psychic foundation of the attribution of meaning is based on this primordial act of affective sharing, of cognitive co-evolution supported by the singular vibration of a voice, a body, a sensitivity.

What happens, then, when the singular voice of the mother (or anyone else) is replaced by a machine? The meaning of the world is replaced by the functionality of signs that allow us to produce operational results from the reception and interpretation of signs devoid of affective depth and, therefore, of any intimate assurance. The concept of precariousness here takes on its full psychological and cognitive meaning as a weakening and dis-erotization of the relationship to the world. In question here is eroticism as the fleshy intensity of experience, and desire in its (non-exhaustive) relationship with eroticism.

Desire and sexuality

Typically, we associate desire with the flesh, with sexuality, a body approaching another body. But we must emphasize that the sphere of desire cannot be reduced to its sexual dimension, even if this implication is inscribed in history, in anthropology, and in psychoanalysis. Desire is not identified only with sexuality, and moreover one can conceive of a sexuality without desire.

In the concept (and in the reality) of desire there is something more than sex, as the Freudian concept of “sublimation” shows us, which concerns the indirect sexual investments of desire itself.

The pandemic has completed the process of the de-sexualization of desire that had been underway for a long time, as soon as the communication between conscious and sentient bodies in physical space was replaced by the exchange of semiotic stimuli in the absence of bodies. If this dematerialization of the communicative exchange has not erased desire, it has nonetheless moved it into a purely semiotic (or rather: hyper-semiotic) dimension. Desire then evolved in a de-sexualized, or post-sexualized, direction, which now manifests as a condition of isolation that the pandemic has normalized and almost institutionalized. The theory and practice of psychology, psychoanalysis, and also the practice of politics are to be questioned, because the underlying subjectivity has been upset and transformed in an irreversible way.

The Italian psychoanalyst Luigi Zoja published a book on the exhaustion (and the tendential disappearance) of desire; indeed, the title is Il declino del desiderio (The decline of desire).6 The book is full of very interesting data on the dramatic reduction in the frequency of sexual contact between people today, as well as the time dedicated to bodily contact in general. But the central hypothesis of the book, the disappearance of desire, seems questionable to me. In my opinion, it is not desire in itself that is destined to disappear, but rather the sexualized expression of desire. The phenomenology of contemporary affectivity is increasingly characterized by a dramatic reduction in contact, pleasure, and the psychic relaxation that touch makes possible. This is coterminous with a loss of sensual trust, a loss of that feeling of deep complicity that makes social life tolerable: the pleasure of the skin that recognizes the other through sensual touch, the sweet enjoyment of the intimacy of the gaze.

The Perversion of Desire and Contemporary Aggressiveness

The de-sexualization of desire indeed risks transforming desire into a hell of loneliness and suffering just waiting to be able to express itself in one way or another. The senseless violence which explodes more and more often in the form of armed and murderous attacks on innocents—the killing sprees which have multiplied everywhere since Columbine in 1999 and for which the United States is the main theater—is only the tip of the iceberg of a phenomenon that at the political level is upsetting the history of the world. How can one explain the election of someone like Donald Trump or Jair Bolsonaro by half the North American or Brazilian people, if not as a manifestation of desperation and self-contempt? The election of a person who openly expresses racist or even criminal remarks has deep analogies (at the psychological level, but also at the political level) with the killings that can only be explained by a suicidal desire.

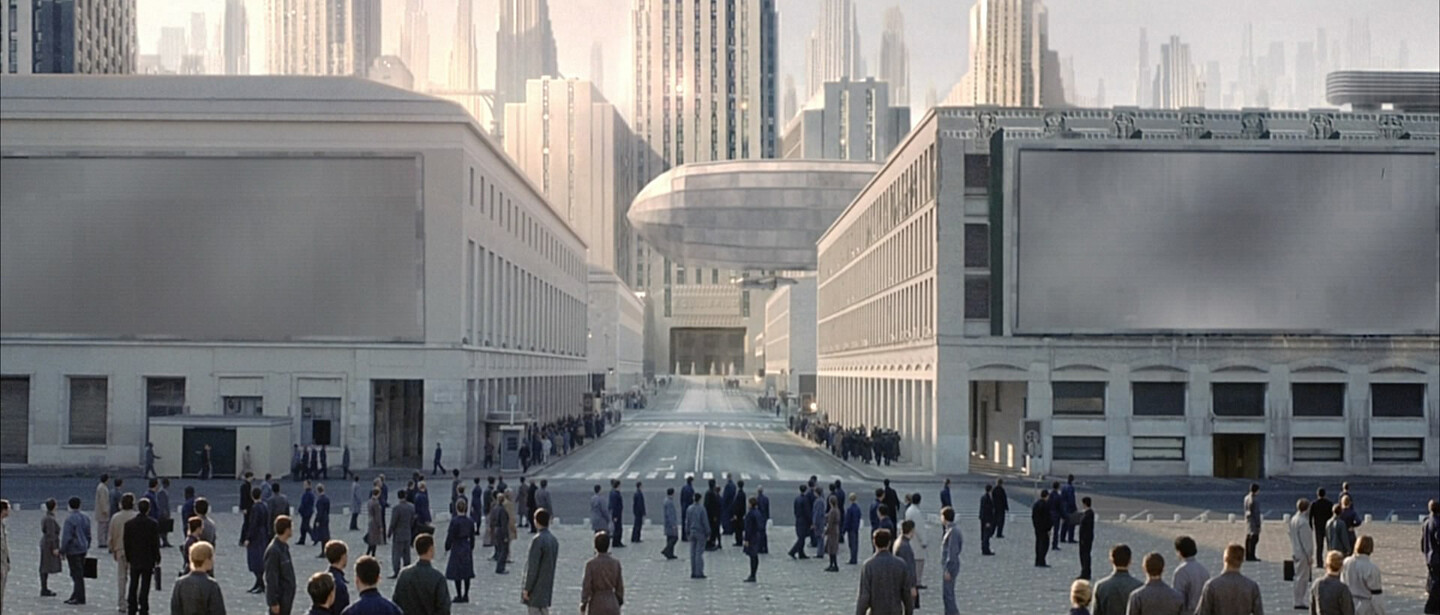

Kurt Wimmer, Equilibrium, 2002. Film still. In an oppressive future where all forms of feeling are illegal, a man in charge of enforcing the law rises to overthrow the system and state.

What we call “fascism” today must be explained in terms that are not only political. Politics is only the spectacular terrain on which these movements manifest. While sharing a rhetoric that is very close to historical fascism, contemporary right-wing movements do not have any rational content.

Only the discourse of humiliation, loneliness, and despair can account for this worldwide phenomenon.

The members of the generation defined, with ironic bitterness, as the last one (Z), those human beings who have learned more words from a machine than from the singular voice of a human, have grown up in an environment that is increasingly unlivable and pathogenic, either at a physical level (pollution) or at a psychic level. The communication of this generation unfolds almost exclusively in a techno-immersive environment, the consistency of which is purely semiotic. Extinction looms as an experience of techno-immersive simulation. Media production is increasingly saturated with signs of this despair. These signs act as signals of unease, but also as factors that help to spread pathology. I am thinking of films like Joker, Parasite, and shows like Squid Game, as well as a thousand other similar products.

The viral trauma of the Covid pandemic only multiplied the effect of the hyper-semiotization of the environment, but the technological and cultural conditions of the phenomenon were already there.

A mutation is reinventing desire: it is expressed less and less in a sexual form, but rather in a semiotic form. Desire has not ceased to be the driving force in the process of collective subjectivation; but the process of subjectivation takes the shape of anxiety, self-mutilation, or sometimes of aggression because desire is perverted into purely phantasmatic forms.

The de-sexualization of desire, the traces of which are everywhere, translates at the social level as a de-historicization of the motivations for collective action. We are witnessing a massive phenomenon of disengagement: majority abstention from traditional politics, desertion from procreation, the abandonment of work. This phenomenon must be the object of a theoretical analysis (diagnosis) and must lead to the creation of strategies for psycho-political collective action (therapy).

This is an edited transcription of my contribution to the congress dedicated to Felix Guattari that took place in Paris in October 2022, the thirtieth anniversary of the death of the author of Chaosmose.