Tuesday, October 17, 2023

Why it pays to read for acrostics in the Classics | Aeon Essays

Politics at Sunset: Theses on Benjamin

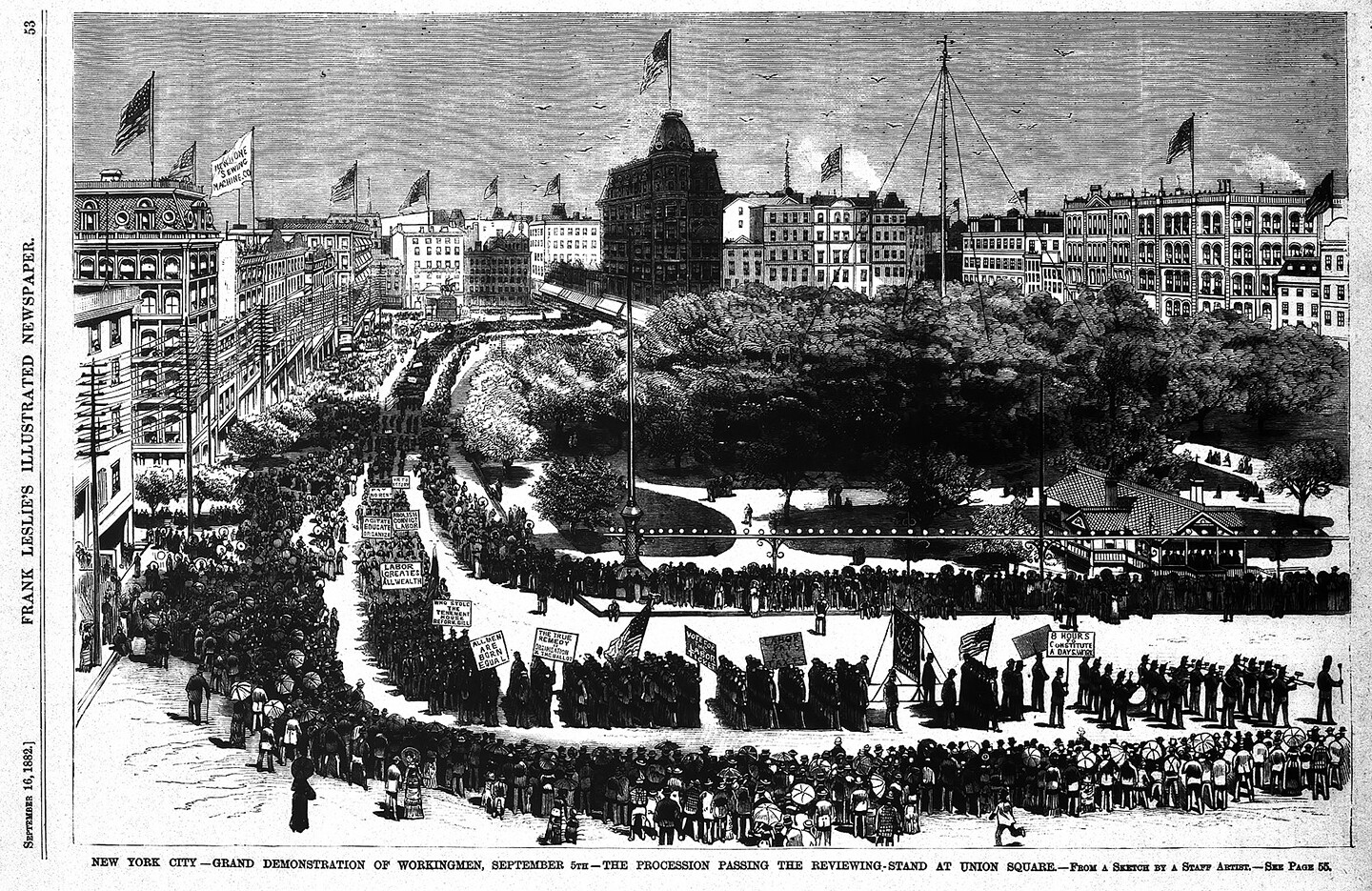

Illustration of the first Labor Day parade in the US, held in New York City on September 5, 1882. The image appeared in the September 16, 1882 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. License: Public domain.

I. The workers movement wasn’t defeated by capitalism. The workers movement was defeated by democracy. This is the problem which the century puts to us. The matter in front of us, die Sache selbst, that we must now try to think through.1

II. The workers movement settled accounts, one to one, with capitalism. A historic confrontation between the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. An alternation of phases. Reciprocal outcomes comprised of victories and defeats. But workers’ labor power, an integral part of capital, couldn’t escape its condition. The obscure basis of revolution’s defeat lies there. The attempts to change the world, whether rational or crazy, all failed. The reformist long march had no more success than the storming of heaven. But the workers did change capital. They forced it to change itself. No workers’ defeat in the social sphere. An emphatic defeat on the political terrain.

III. The twentieth century is not the century of social democracy. The twentieth century is the century of democracy. Traversing the era of wars, democracy imposed its hegemony. It was democracy that won the class struggle. In this century, authoritarian and totalitarian political solutions functioned finally as diabolical instruments of a democratic providentialism. Democracy, like the monarchism of yesteryear, is now absolute. More than the practice of totalitarian democracies, what stands out is a totalizing idea of democracy. At the same time, paradoxically, as the dissolution of the concept of “people” foreseen by Kelsen’s genius. After the defeat of nazifascism and after the defeat of socialism, twice over, it was elevated to the status of a choice of values. The workers movement did not elaborate, let alone practice, either in the East or the West, its idea of democracy. It didn’t grasp it, didn’t experience it, as a locus of conflict. The workers movement of the twentieth century could not help but be democratic. But the century of democracy killed it. This trauma is lodged, and obscurely acts, in the collective unconscious of the European left, in the activism, the leadership, the culture.

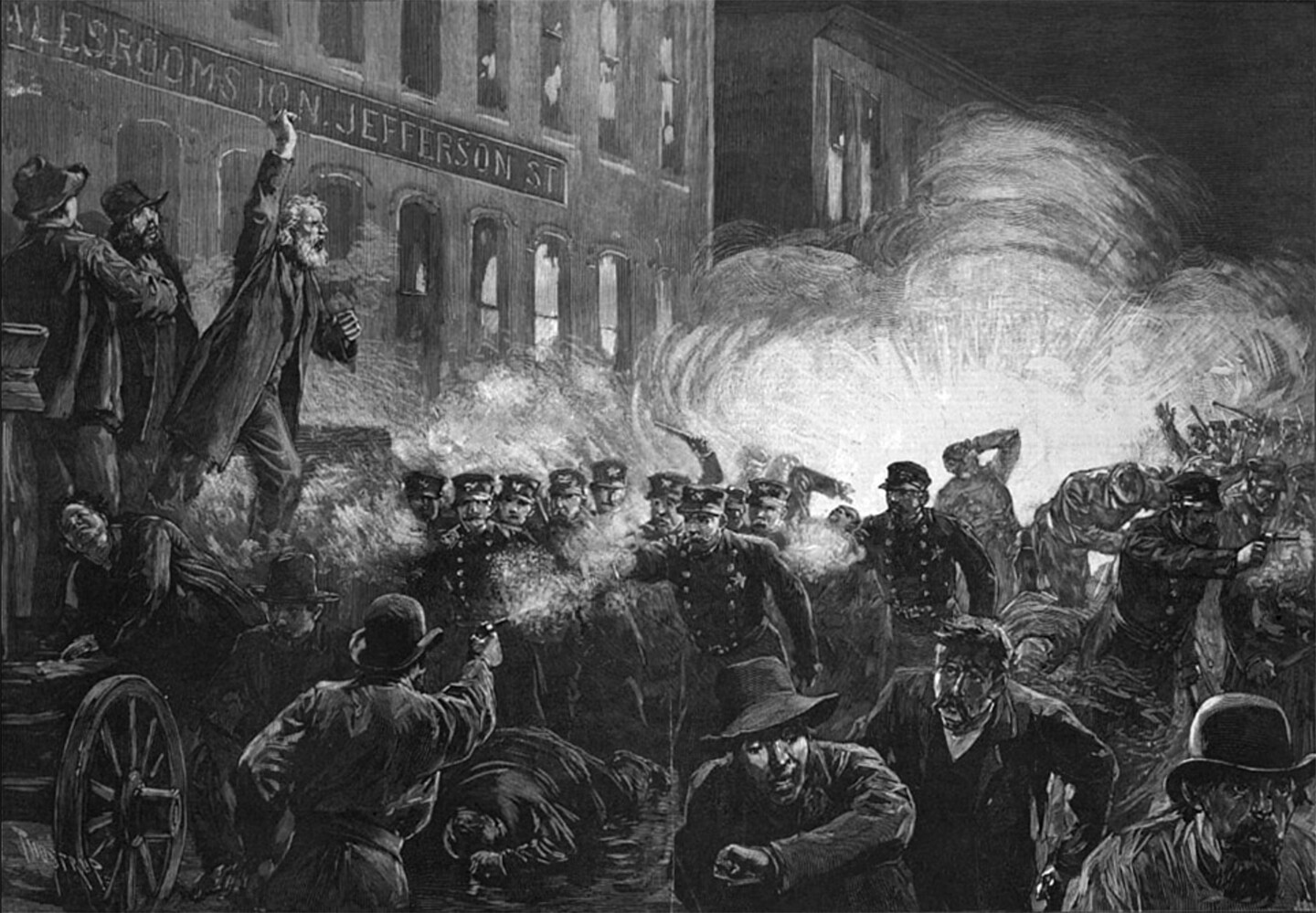

Published in Harper’s Weekly on May 15, 1886, this image depicts the events of the Haymarket Riot in Chicago, when a bomb was detonated as police officers attempted to disperse a labor protest. The events of the day are now commemorated each year on May 1. License: Public domain.

IV. Tocqueville had a prophetic glimpse of the anti-political future of modern democracies. The punctual arrival of political demoralization, and the completion—in this close of the twentieth century—of political atheism. That great liberal saw the end of modern politics realized in American democracy, a powerful indication of the world’s future. In the Tocquevillian distinction between the science of politics and the art of government, Umberto Coldagelli had the intelligence to grasp the “substantial dualism” between democracy and liberty. With this immediate consequence: “The preservation of liberty comes to depend solely on the ability of the art of government to oppose the spontaneous tendency of the ‘political state’ to merge with the ‘social state.’”2 And he reports this variant of La Démocratie which dates from 1840: “The ‘social state’ separates men; the political state must draw them together. The social state gives them a taste for well-being, the political state must give them great ideas and great emotions.” In bourgeois modernity there is, as its distinctive sign so to speak, a “natural” subjectivity favoring social action and an “unnatural” subjectivity favoring political action. “Consciousness and ideas do not renew themselves, the soul does not grow and the human mind does not develop, except through the reciprocal action of men upon one another. I have shown that this action is almost non-existent in the democratic countries, so it has to be created artificially.”

V. The artifice of the political relation as opposed to the natural character of the social relation is not a Jacobin invention, nor a Bolshevik imposition. It is the condition of the political in modernity. We can put this another way: political civilization versus natural society. Today it’s possible to translate this choice into the decision freedom or democracy. Contrary to what people think—Tocqueville informs us—the natural-animal element is democracy, the historical-political element is freedom. Now that political science describes the need for democracy, the task of the art of government consists in introducing freedom. A different political freedom: after the freedom of the moderns, without falling back into the freedom of the ancients. While the dictatorships rekindled the passion for freedom, it’s not so paradoxical that the democracies extinguished it. If The Philosopher Reading painted by Chardin were to peruse the book by Georges Steiner, and no longer his folio from back then, I think he would confirm Milton’s verse: “all passion spent.”3 The century of democracy which defeated the dictatorships in war, did not give freedom in peace. And in these last days of the twentieth century, this historic confrontation between dictatorship and freedom, which has seen the defeat of totalitarianism and authoritarianism, leaves on the battlefield, precisely without passions, something like a residue of a war that no one provoked, the political conflict between democracy and freedom. Deciphering that passage is a challenge for thought, but the practice it implies is no less puzzling. The victorious ideological apparatus, the accumulation of dominant consensus, and the “social power” that results from them are all conjoined now under the rubric of liberal democracy. Insert a wedge into this practical-conceptual liberal-democratic ensemble. Pull out the two potentially contradictory terms. It’s only on the battlefront of this good war that serious politics can return.

VI. An idea of liberty in contrast with the practice of Homo democraticus. An idea of democracy in contrast with the practice of Homo economicus. Pressing on these two keys with the fingers of thought, we must try to reactivate the search for new forms that could make political action meaningful again. On one hand “mores” and “beliefs,” on the other the “taste for material well-being” and “softheartedness.” Democracy ensures and promotes the latter, and liberty needs the former. This requires choosing. Because they are alternatives. A new spirit of scission is called for. Divide the neutral citizen into two different kinds. For each one, convert the modern individual into a human person. Reconnecting the past to the future can be accomplished only if both are divided in terms of the present. We can no longer consider, along with Benjamin, now-time (Jeztzeit) as the site of the Marxian revolutionary dialectical leap. We are still constrained, with Heidegger, to consider the “present time” (Jetzt-zeit) as Weltzeit, inauthentic world time. Here too, between time and the present time, between the epoch and the today, one must strike with the red wedge of living contradiction. The white circle is this world, dead hereafter.

VII. Not liberty from and liberty relative to, positive liberty or negative liberty, liberty and freedom, liberty of the ancients and liberty of the moderns. Nor even a political philosophy of liberty, which was provided by liberalism. But a philosophy of liberty, the one that Marxism wasn’t able to provide. The object of the first was external liberty, both juridical and social, the constitutional liberty of the market, the public guarantee for the private atom, rights, precious and paltry, precious for living with others, paltry for existing on one’s own. The object of the second is human liberty, the kind that Marx attributed to the “eternal dignity of the human race,” the preter-human liberty of Christianity, the mentis libertas beatitudo of Spinoza, the unsolitary solitude of the great spirit, to cite the expression of the philosopher of existence, Luporini. The error of the Marxist horizon is not in having critiqued the libertas minor, but in having done so without a contemporary, theoretical and practical, assumption of a libertas major. Hence the political disaster. It is only on behalf of a genuine human liberty that a critique of the bourgeois false liberties could be undertaken. A critique that is destructive of their apparent human generality and yet that inherits the positivity of their modern basis, while avoiding the latter. In Kantian terms: inadequacy of the Unabhängigkeit, of the independence of individuals, but at the same time its condition of possibility, its transcendentality, for establishing liberty as autonomy of the human being, carrying the moral law within oneself.

VIII. Homo democraticus, the isolated and massified individual, as globalized as he is “particularized,” guided from outside and from above even in the garden that he cultivates, an individual in the herd, the last man, described, before Nietzsche, by Goethe, as the subject of the times he saw arriving, “the era of commodities,” a “very anxious and questionable” expression, Thomas Mann will say. The era of commodities and of vulgarity. Mann will find this accent again, in fact, reaching dizzying and truly extraordinary peaks, in 1950. Meine Zeit, my time, “the age of technology, of progress, of the masses,” “while I did express it, I was rather opposed to it.” But he goes on to say: “It’s always risky to believe one is privileged owing to the special historical abundance of one’s epoch, because a more complicated time can always come, and because it always does come” (Doctor Faustus). Between the middle of the nineteenth century and the end of the twentieth century, it’s easy to see the realization of the tragedy of socialism, and harder to grasp the consummate drama of democracy. But that is when democracy definitively accepted the role of the public function of Homo economicus. A democracy of interests: this was its final name. During those fifty years democracy was corrupted, or completed, depending on whether one considers the problem from the viewpoint of the radical democrat or that of the critic of democracy. For my part I think it was completed. An unreformable democracy, like socialism was unreformable? This is the uncertainty of the defeated, I would like to say to Petro Ingrao. To dispel it, to try and dispel it, one must abandon intellectual games and take on the difficult complication that has come into politics.

IX. About Musil’s character, “who serves as a mirror to the world of his time,” Ingeborg Bachman has written: “Ulrich understood early on that the era he lived in, equipped with a knowledge superior to any other preceding era, an immense knowledge, seemed incapable of intervening in the course of history.”4 What was understood early on was forgotten early on. To the point that no one has realized that history is epochless. And in fact, nothing happens. There are no longer events. There is only news. Look at the figures standing atop empires. And reverse Spinoza’s phrase. Nothing to understand. Only things to lament, or laugh about. Athens and Jerusalem gaze in disbelief at what the end of a millennium, ancient and modern at once, has produced. The end of communism and a Christianity of the end, those two symbolic orders that remain to be interpreted in their entirety, obscure deposits in the folds of contemporary consciousness, bring time to a close: but—and this is what’s new—without apocalyptic tensions and in the silence of signs. The desperate cry of Father Turaldo: “Send more prophets, Lord / … to tell the poor ones to keep hoping / … to break the new chains / in the infinite Egypt of this world.” The real God that failed, the real defeat of God, in this century, is in the promise and in the human liberty unattained, for each man and woman, for all women and men. This is the where the discourse is headed: this liberty in interior homine, need or negation, to go take hold of it, unveil it, in the tragic history of the twentieth century. And set out again from there: not new beginnings, but interrupted paths.

X. Walter Benjamin to Stephan Lackner, May 5, 1940: “One wonders if by chance history was not in the process of forging a brilliant synthesis between two Nietzschean concepts, namely the good European and the last man. On might obtain the last European as a result. We are struggling not to become that last European.” A terribly up-to-date reflection, and a wonderful example of prophetic political thought. The embodiment of the last man in the good European is now taking place before our disenchanted eyes, programmed for completion according to a financial-economic calendar decided on democratically. Here everything just happens. The event becomes a fact in its purest form. Europe is born in the same manner as the century dies: without passion, from the exhaustion of states and in the interest of individuals. History becomes the synthesis of what is. What should be does not concern it. Politics was supposed to slay, not represent, the last man. But as I’ve said: the end of modern politics. And that suits everyone just fine. Everyone is fighting to become the last European. The competition is taking place on the market square: where one hears “the noise of big comedy” and at the same time “the buzzing of poisoned flies.” In the face of this epochless history we are only left with the choice between two anthropological perspectives. Bloch used to say: man is something that needs to be discovered. Nietzsche: man is something that must be overcome. Perspectives, the first being alternative, the second antagonistic. Until a short while ago, we would have said: politics is one thing, theory is another. Not any longer. It’s becoming clear that we must resolve each thing within our thought. If the decline of the West will be completed in a Spenglerian fashion “in the first centuries of the next millennium,” the decline of politics will play out in the first decades of the next century. Thought is assigned the task of fore-telling, while speaking on behalf of history’s vanquished. In the meantime, there is nothing to be discovered about man. The beyond-man is entirely to be thought.

XI. The ideal sequel to Marx’s eleventh thesis on Feuerbach, or, let’s say, its reformulation for the twentieth century, is the twelfth thesis by Benjamin in his “On the Concept of History” (but see also the lemmas “Future” and “Image”). Let’s read: “The subject of historical knowledge is the struggling oppressed class itself (die kämpfende, unterdrueckte Klasse). Marx presents it as the last enslaved class—the avenger class (die rächende Klasse) that completes the task of liberation in the name of generations of the downtrodden.”5 A given of consciousness that’s always been inadmissible for social democracy. The latter “always preferred to cast the working class in the role of a redeemer of future generations, in this way cutting the sinews of its greatest strength. This indoctrination made the working class forget both its hatred and its spirit of sacrifice, for both are nourished by the image of enslaved ancestors rather than by the ideal of liberated grandchildren.” It’s rare than one can subscribe to every word of a thought. Yet this is the case. This is what it means to reverse a perspective in terms of the side one is on. The “avenger class,” the last to be enslaved but also the first to possess the necessary strength. A political rather than ethical motivation for being on that side. To avenge an eternal past of oppression endured. That past is the new subject of history, therefore, which alone can carry out a new political action. The future was grounded in this passion, sensed and preserved in the body of struggles of our own past. And this passion was extinguished by the dogmatic claim, typical of social democratic theory and practice, of an “unlimited,” “essentially continuous” progress of humanity, as if history advanced through a “homogeneous and empty time” (see Thesis XIII). Hatred unlearned, together with the will to sacrifice, two communist and Christian virtues. Severed, the sinews of strength, the kind that matters in the conflict. Overturned, the meaning of action, which is Image and not Ideal: an image of defeated comrades, and not an ideal of redeemed brothers. Redemption does in fact concern “the oppressed past,” it does not indicate the radiant future. What is great, or what is destined to be great, is only this historical movement, or this political object, capable of translating the contents of what was into the forms of what is to arrive, always, always, always against the present.

Velvet Revolution, Prague, November 17, 1989. Photo: Prague City Gallery.

XII. “In the idea of classless society, Marx secularized the idea of messianic time. And that was a good thing. It was only when the Social Democrats elevated this idea to an ‘ideal’ that the trouble began. The ideal was defined in Neo-Kantian doctrine as der unendliche Ausgabe (as an ‘infinite task’). And this doctrine was the school philosophy of the Social Democratic party” (Thesis XVIIa). Here homogeneous and empty time became an antechamber where it was a matter of waiting for the revolutionary occasion. “In reality, there is not a moment that would not carry with it its revolutionary chance.” What counts is a given political situation, but equally “the right of entry which the historical moment enjoys vis-à-vis a quite distinct chamber of the past, one which up to that point had been closed and locked. The entrance into this chamber coincides in a strict sense with political action” (ibid.). It’s essential to be able to recognize “the sign of a messianic arrest of happening”—that is, be able to grasp the sign of “a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past” (Thesis XVII). And there as well, a good thing. But what about times without signs? When history sleeps, should politics wake it up, or go to sleep beside it, abandoning all vital activity? Even the Christian Dossetti told us that politics is contingency, chance, occasion: not from time to time, but again and again, day after day. So the revolutionary chance is not to be waited for, one seizes it; it doesn’t arrive, it’s already there, in heterogeneous and full time. Politics can regenerate itself. It can transcend its modern character, on the sole condition that it claims the “right of entry” in a different sense, contrary to that which made it function as a future-oriented project, implicit in the present and springing from it. It has to decide to modify the past, to change all that has been, to open the closed chamber of history, producing the moment in which what always occurs is interrupted. Not wait for the signs of the times, but create them. Because the signs don’t make the event visible, they are the event. Demonstrate in the contingency of quotidian action that whatever you bind on earth “shall be bound in heaven” and that whatever you loose on earth “shall be loosed in heaven” (Matthew 16:19). The end of the politics of the moderns isn’t the end of politics, and isn’t the return of the politics of the ancients. It’s the occasion of that discontinuum in politics which the given situation doesn’t offer but the revolutionary chance can impose.

XIII. A revolution in the idea of politics: this is the first right of entry that’s consigned to us by the oppressed past and by generations of the vanquished. Because revolution as political praxis is what must be brought under the scrutiny of critique. There is no longer any distinction between revolutionary action and revolutionary process. No chance in either. The question is no longer whether the revolutionary subject is the class or the party. The arrest of happening is not the doing of a will to power. The very Marxian “dialectical leap … under the free sky of history” has crashed, wings broken, to the arid ground of politics. The point of difference is no longer between reformist gradualism and revolutionary rupture. It is between continuity and discontinuity. And since in continuity no reformist practice is possible henceforth, discontinuity is no longer identified with revolution. The revolutionary chance is not revolutionary action. It is a point of view, a political mode of being, a form of political action, the now, always, of political behavior. In the face of, against, the “reified continuity of history,” politics is exercised in nature through “intermittent units” of actuality, where “everything that is past … can attain a higher degree of actuality than at the moment of its existence” (see the lemma “Continuum”). Among the materials preparatory to the Theses, some piercing thought projectiles: “The history of the oppressed is a discontinuum,” which is to say, “history’s continuum is that of the oppressors.” The concept of the “tradition of the oppressed” is seen as the “discontinuum of the past versus history as the continuum of events.” But consider: Is the point of catastrophe to be placed in the continuity of history, as the late Benjamin seems to think, or should it be cultivated in the discontinuity of politics, as the end of this century seems to indicate? Here is the in-decision of research, which looks at the extreme aspects of the horizon of problems, no longer with the hope of finding solutions, but rather with the responsibility of escaping the affliction of the time, which consists in being subordinated to a present future.

Titian, Allegory of Prudence, c. 1560–70, oil on canvas. National Gallery, London. License: Public domain.

XIV. EX PRAETERITO / PRAESENS PRUDENTER AGIT / NE FUTURA ACTIONẼ DETURPET (“From the experience of the past / The present acts prudently / Lest it spoil future action”): this is the statement inscribed at the top, divided in three, next to a triad of heads of men and animals, of Allegory of Prudence, or Allegory of Time Governed by Prudence, which the aged Titian painted between 1560 and 1570. The wolf of the past, the lion of the present, the dog muzzle of the future. Panofsky says that the painting glorifies Prudence as a wise user of the three Forms of Time, associated with the three ages of Life. “Titian did not break away from a well-established tradition, apart from the fact that the magic of his brush gave a palpable appearance of reality to the two central heads (that of the man in the prime of life and that of the lion), whereas one could say that he dematerialized the profile heads of the two sides (those of the old man and the wolf on the left, and those of the young man and the dog on the right): Titian gave visible expression to the contrast between what is and what has been or has not begun to be.”6 Prudence, a major category of modern politics, has marked the chance and mischance of the twentieth century and, according to the cases, has produced the century’s conquests and tragedies. It is the “sad science” of the doctrine of the state in the time of the absent sovereign. The present must know from the past those things which above all must not arrive in the future. This is the variance [écart] that actuality compels us to maintain henceforth: defend ourselves from the form of the future which all the contents of the present are constructing. Actuality: Father Time in the Great Epoch, the “lion” without the “fox,” force without prudence, politics without politics—that is, history abandoned to itself, minor, cyclical history, eternal return of always the same, accelerated, modernized, for internal conservative revolutions. The old face of the wolf is the tiger’s leap into the past that Benjamin talks about. The mature face of the lion is the great twentieth century, which has faded into the current reified continuity of history. There results a virtual abstract domesticated form of future. Act now so that what comes after does not spoil the action. But does the standard of the political still stand a chance, revolutionary or not, in the current contingency of the historical event?

XV. Kultur und Zivilisation: take up the broken thread of a discourse, take it up at the end of this century starting from the place of its beginnings. In our own words, suited to today, the distinction being: Zivilisation is modernity, Kultur is civilization. One could say bourgeois modernity and human civilization. But that would introduce an excessive emphasis that’s no longer à l’ordre du jour. The bourgeois and the human are no longer inflected according to the rules of the nineteenth century. Today’s bourgeois is the “last man.” Just as today’s man no longer bears any resemblance to yesterday’s bourgeois. Just as the Bürger [citizens] of Thomas Mann, “our” Mann, pre-1918, are the contrary of the bourgeois, and just as the Arbeiter [workers], not that of Jünger, but precisely that of Marx, are the contrary of the citizen. Our dream: the coarse pagan race with, in its own right, the culture of the grand-bourgeois, “that grand and severe, deeply moving bourgeoisness of the soul” which Claudio Magris speaks of in reference to Mann’s Buddenbrooks. Contrariwise, between these two things, modernity/civilization, an eternal absolute historical conflict, next to a temporary political consensus. In the different passages of the twentieth century, consensus and conflict have been expressed in different forms. The age of wars radicalized the contradiction between Kultur and Zivilisation, but the peacetime that followed did not even pose the problem to itself. It’s a question of seeing if one can recover the civilizing function which the workers movement had before the war shoved it into the trenches. Twentieth-century war and peace have sequestered this legacy. To reclaim it there have to be heirs: a movement of ideas and forces capable of injecting the body of modernity with the spirit and the forms of a Kultur, a Zivilisation. It matters little whether it’s new, it can even be ancient; what is important is that it show the signs of a contrast to the current barbarization of the human social relation. Civilize modernization: this is the task in which everything consists, on which everything must be focused, struggles, organization, government, projects, tactics. Injecting Kultur into the irrepressible objective processes of globalization, digitalization, virtualization. The more the danger of this modern barbarism grows, the more the saving power can contribute to retaining and messianically arresting the event. I see more katechon than eschaton in our “What is to be done?” after the end of modern politics.

XVI. “Aber Freund! wir kommen zu spät”—“But friend! We come too late” (Hölderlin, “Brot und Wein,” 1801). Such is the Stimmung [mood] that connects the figures and the motifs, the passages and the halts, the prestos and the adagios of reflection. The century of great opportunities transformed itself into the century of small occasions. In politics, possibility is always tragic. The comedy of probability leaves everything as is. One could have not done what was done. But one could also have done what was not done. With this binary schema in mind, research has several paths to follow. No longer in darkness. Even if: Isn’t it strange, this light that politics at its sunset casts on the history that has just passed? “Aber das Irrsal hilft”: we’re helped by “drifting,” errance, error.

This text was originally published in Mario Tronti’s La politica al tramonto (Einaudi, 1998). It appears in English here for the first time. In January 2024, a new edition of La politica al tramonto will be published by DeriveApprodi.

Umberto Coldagelli, introduction to Alexis de Tocqueville, Scritti, note e discorsi politici (1839–1852) (Bollati-Boringhieri, 1994), xvi.

Georges Steiner, No Passion Spent: Essays 1978–1995 (Yale University Press, 1998).

Ingeborg Bachman, Il dicible e l’indicible (Adelphi, 1998), 21–22.

Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” in Selected Writings, vol. 4, 1938–1940, trans. Edmund Jephcott et al., ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Harvard University Press, 2003), 394.

Erwin Panofsky, Tiziano (Marsilio, 1992), 105. Also see the Titian chapter in Panofsky’s Meaning in the Visual Arts (University of Chicago Press, 1983).

Where Have All the Pithiatics Gone?

Where Have All the Pithiatics Gone? Robert Boncardo and Christian R. Gelder on Lacan and French psychiatry 4 Dec. 2025 Reviewing Jacques L...

-

撰文 | 李硕(中国科学院国家天文台) 编辑 | 韩越扬 提起天文学家,我们脑海里最先想到的可能就是一群夜猫子。他们昼伏夜出,没事喜欢守在望远镜前,不知道在捣鼓些啥,总之看上去很厉害就是了。或者,像有些科幻电影里的角色一样,手里抱本厚厚的《星系动力学》,办公室黑板上写满了连符号都...

-

入声是如何逐渐消失的? 关于入声消失的历史过程还是没有概念,据我的朋友说这个过程是从唐就开始了,可以上溯到清浊的消失什么的。能不能更加清晰的描述下这个脉络? 关注者 382 被浏览 35,160 关注问题写回答 6 条评论 分享 邀请回答 5 个回答 默认排序 苏倏 关注在线教育...

-

《容安馆札记》656-660则 六百五十六 呂留良《何求老人集》言敦源校錄、《東莊詩集》風雨樓叢書。誤字過多,思之不適。合本稍善,勘正亦少,又僅至《夢覺集》之半而止耳。晚村詩風格出入黃...