In praise of dirty, sexy cities: the urban world according to Walter Benjamin

Seventy five years after his death, the Marxist philosopher's passion for the seedier, messier delights of cities such as Marseille and Moscow are a stark reminder of how sanitised today's urban environment is becoming

Modern Marseille is being sandblasted, primped and cultureified. Photograph: Alamy

arseille isn't as wicked as it used to be. In 1929, the playwright and travel writer Basil Woon wrote From Deauville to Monte Carlo: a Guide to the Gay World of France, warning his respectable readers that, whatever they do, they should on no account visit France's second city. "Thieves, cut-throats and other undesirables throng the narrow alleys and sisters of scarlet sit in the doorways of their places of business, catching you by the sleeve as you pass by. The dregs of the world are here unsifted … Marseille is the world's wickedest port."

Much has changed since 1929. Gay doesn't mean what it used to mean. Marseille isn't the world's wickedest port, but subject to one of Europe's biggest architectural makeover projects. It has become respectable enough to serve as European Capital of Culture in 2013. Its port has been sandblasted and civilised. Throughout the city – Eurostar's latest destination from London – there are new trams, designer hotels, luxury flats and high-rise developments.

The last of these changes is freighted with symbolism. Marseille has been overwhelmingly horizontal since Greek graders founded it 2,600 years ago, its terracotta-roofed buildings spreading inland from the bay. Now it's going vertical, with new skyscrapers glassily returning your gaze, looking like a Mediterranean sibling for those other formerly raffish docklands made safe for business suits – London, Hamburg and Baltimore.

The worry is, as Marseille comes to look like everywhere else, it loses what made it special – the saltiness, the wickedness, the downright smelliness so off-putting to some.

Rue de l'Amandier in Marseille, 1920. Photograph: Adoc-photos/Corbis

"Marseille – the yellow studded maw of a seal with salt water coming out between the teeth," wrote the critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin. "When this gullet opens to catch the black and brown proletarian bodies thrown to it by ship's companies according to their timetables, it exhales a stink of oil, urine and printer's ink …"

Benjamin wrote these words for a newspaper article in the same same year as A Guide to the Gay World of France excoriated Marseille. Unlike Basil Woon, he revelled in the city. Another French city, Toulouse, called itself la ville rose, the pink city, but for Benjamin, pink was more truly the colour of Marseille. "The palate itself is pink, which is the colour of shame here, of poverty. Hunchbacks wear it, and beggarwomen. And the discoloured women of Rue Bouterie are given their only tint by the sole pieces of clothing they wear: pink shifts."

What Benjamin wrote about cities in newspaper essays in the 1920s and early 1930s, as well as in his book about 19th-century Paris, The Arcades Project, remains fascinating and instructive, and not just because he was one of the first thinkers to suggest that urban living intensified feelings of isolation and atomisation.

What makes this German Jewish philosopher even more compelling is that he also found the opposite in cities – flashes of the utopian in the abject – and realised they could provide solutions to, as well be the causes of, alienation. This oddball communist from segregated Berlin interpreted cities such as Marseille, Moscow and Naples as kinds of laboratories that, just possibly, suggested how we might live better.

In his essay Hashish in Marseille, Benjamin described an evening wandering from cafe to cafe after taking the drug (the philosopher stoned): "I now suddenly understood how to a painter – had it not happened to Rembrandt and many others? – ugliness could appear as the true reservoir of beauty, better than any treasure cask, a jagged mountain with all the inner gold of beauty gleaming from the wrinkles, glances, features." Benjamin encountered in his Marseille trance what his beloved Baudelaire had found when taking the same drug in Paris nearly 70 years before: an artificial paradise.

Marseille isn't France. Marseille isn't Provence. Marseille is the world

Robert Guédiguian

But the Marseille Benjamin savoured, and that scared Woon, scarcely exists any more. The red-light district of the Rue Bouterie survives only as collectable postcards from the wicked era of the later 1920s. So too Basso's, one of the restaurants in which Benjamin dined that night, nearly nine decades ago, to stave off the munchies. As I wander the Marseille streets trying, and failing, to follow Benjamin's footsteps, I'm disappointed: the people are insufficiently ugly. Perhaps if I'd been on hashish like Benjamin …

A different Marseille – sandblasted, primped and cultureified – is rising in its place. On the Quai d'Arenc, where once Benjamin found beauty in ugliness, an old silo building has been repurposed as a 2,000-seater auditorium. Elsewhere, an old chateau has been converted into the Centre for Mediterranean Cinematography, a Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations and, my personal favourite, a museum devoted to La Marseillaise, the French national anthem where, depending on your taste, you can hear Serge Gainsbourg croaking a reggae version of Stephane Grappelli.

But the worry here is that what Benjamin's colleagues of the Frankfurt School – Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer – excoriated as "the culture industry" becomes a means of ripping the soul out of the place while making it look as though the opposite is happening. Without being unduly cynical, culture has become part of capitalism's sanitising redevelopment of one of the most cherishably wicked of world cities.

Zaha Hadid's 147-metre-high Tour French Line tower rises above Marseille. Photograph: Jose Nicolas/L'Oeil du spectacle/Corbis

The focus of that redevelopment, Euroméditerranée, is among the biggest renovations schemes in Europe. It echoes what Marseille's twin city of Hamburg is doing at HafenCity – the German port's former docks – and similarly risks making the raffish respectable, the salty sweet, the wicked merely nice. That, so often, has been the fate of docklands redevelopments: think of London's Docklands now devoid of opium dens and free-swearing dockers. It risks, that is to say, obliterating everything Benjamin liked about Marseille.

New Marseille is typified by Zaha Hadid's 147m-tall Tour French Line, the corporate headquarters for shipping container company CMA-CGM. Jean Nouvel has designed three more skyscrapers for the city which, to sceptics, are excellent ways of making Marseille lose its identity.

According to the French film director Robert Guédiguian, who sets most of his films (including Marius et Jeannette and La Ville est Tranquille) in and around his home city: "All that squeezes itself between the buildings, that insinuates itself between the architectural drawings and political plans, must be carefully preserved because it is there that one finds the city's future."

For Guédiguian, what squeezes itself between these plans is a much more interesting city – a multi-ethnic metropolis that includes 120,000 north African immigrants whose presence has led to Marseille being called Sahara on Sea. "Marseille isn't France. Marseille isn't Provence. Marseille is the world," says Guédiguian.

So what would Walter Benjamin have made of the new city that is rising over the traces of the one he loved? What's striking about his vision of the former city is how sensitive he was to false utopianism, to the bulldozing of the past and the dreams of progress.

Benjamin was always drawn to outmoded utopias – the formerly state-of-the-art technology, the ruins of progress …

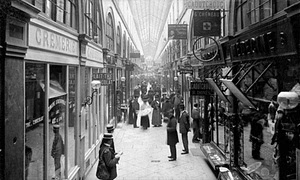

Le Passage Choiseul shopping arcade in Paris, circa 1900. Photograph: Roger-Viollet/AFP

The Arcades Project – that great ruin of a book he spent the last decade of his life assembling, until his suicide in Spain 75 years ago this month while on the run from the Nazis – focuses on the fading arcades of 19th-century Paris, in which once-fashionable shops, goods and building styles hung on briefly before Baron Haussmann destroyed them in favour of a yet-newer Paris. Benjamin was always drawn to these outmoded utopias, the formerly state-of-the-art technology, the ruins of progress – since they encoded, he thought, the delusions that capitalism instilled in its victims.

"Capitalism," Benjamin wrote in 1922, "is a purely cultic religion, perhaps the most extreme that ever existed." By that, in part, he meant that capitalism abases us before the new, subdues us not with opium but with must-have commodities. And cities could be shrines to the cult, too.

To get a sense of this, simply take the tourist boat trip from the Vieux Port along the coast to see the legendary Chateau d'If (where the Count of Monte Cristo was incarcerated) and the Calanques (the limestone cliffs that plunge into the Mediterranean). Look back and you'll see a city skyline that did not exist when Benjamin and Woon wrote. Since 1864, the city was dominated by Notre Dame de la Garde, standing high on a hill on the site of a former fort. Now though, it rhymes with Zaha Hadid's Tour French Line. The Iraqi-British architect says that her tower complements the basilica. It also, though, represents a challenge to it: hers is a glassy temple to a newer deity.

Hadid says her shipping company HQ complements Marseille's Notre Dame de la Garde. Photograph: Hemis/Alamy Stock Photo

In promising newness, progress, built utopias, bulldozing wickedness and poverty, the development of urban landscapes could make the faithful believe more ardently in what – for a communist such as Benjamin – in fact, oppressed them. Again and again, he takes the perspective of one looking back on failed utopias, on the obsolete commodities that were once must-haves. The Benjamin scholar Max Pensky explains the political force of how Benjamin wrote about cities: "The fantasy world of material well-being promised by every commodity now is revealed as a hell of unfulfillment; the promise of eternal newness and unlimited progress … now appear as their opposite: as primal history, the mythic compulsion toward endless repetition."

None of the above should suggest that Walter Benjamin disliked cities. Rather, he found in the ones he really liked – Marseille, Naples and Moscow in particular – antidotes to the socially zoned, ghettoised Berlin in which he had been raised around 1900.

For instance, in 1927, he took a sleigh ride through Moscow. "Where Europeans, on their rapid journeys, enjoy superiority, dominance over the masses," he wrote, "the Muscovite in the little sleigh is closely mingled with people and things. If he has a box, a child, or a basket to take with him – for all this, the sleigh is the cheapest means of transport – he is truly wedged into the street bustle. No condescending gaze: a tender, swift brushing along stones, people and horses. You feel like a child gliding through the house on a little chair."

Ten years after the Bolshevik Revolution, Benjamin was visiting the Soviet capital to study what he called " the world-historical experiment". "Each thought, each day, each life lies here as on a laboratory table," he wrote. Riding on a Moscow tram was, for the pampered Berliner, a new experience – the poor got up close and personal. "A tenacious shoving and barging during the boarding of a vehicle usually overloaded to the point of bursting takes place without a sound and with great cordiality. (I have never heard an angry word on these occasions)."

Each thought, each day, each life lies here as on a laboratory table

Walter Benjamin on 1920s Moscow

A propeller-powered sleigh in Moscow in 1929. Photograph: Planet News Archive/SSPL/Getty Images

For a German Jew born to a wealthy family, this new experience of city life was tremendously exciting. During Benjamin's childhood, in the exclusive suburbs of west Berlin, the poor scarcely existed, still less got close enough to jostle him on public transport. In his memoir, A Berlin Chronicle, Benjamin wrote of his upbringing that "the class that had pronounced him one of its number resided in a posture compounded of self-satisfaction and resentment that turned the district into something like a ghetto held on a lease. In any case, he was confined to this affluent neighbourhood without knowing any other. The poor? For rich children of his generation, they lived at the back of beyond."

In the 1920s, Benjamin spent a lot of time in cities such as Moscow, Naples and Marseille – each in its different way giving him a cure to the disease of modern life in general, and the one in which he had been raised in particular. His compatriot, the German sociologist Max Weber, had written of the iron cage of capitalism inside which humans were submitted to efficiency, calculation and control. Cities were part of that system of control, which worked by keeping the poor and rich in their proper places. The cities that turned Walter Benjamin on were the opposite of that: porous labyrinths annulling class, time, space and even distinctions of light and dark.

Benjamin's enthusiasm for these cities is, nearly 100 years on, contagious. Particularly as so many of the world's leading cities have turned sclerotic – socially stratified cages to keep the riff raff out and the rest of us polishing our must-have Nespresso machines.

In Paris, the poor are banished beyond the périphérique so that when they revolt, they destroy their own banlieues rather than the French capital's fussily maintained environment. London's key workers strap-hang on laughable trains from distant commuter towns to serve the wealthy before being returned to their flats in time for the de facto curfew each day. Manhattan island is today a pristine vitrine on which the lower orders don't even get to leave their mucky paw prints, but inside which the rich get to fulfil with unparallelled freedom their uninteresting desires. I'm exaggerating in each case, but not much. Many of the world's leading cities are becoming like the Berlin that Benjamin called a prison, and from which he escaped whenever possible.

There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism

Walter Benjamin

The monument to Walter Benjamin in Portbou, Catalonia. In 1940 the Jewish philosopher escaped to Spain, but killed himself when he learned the authorities were likely to deport him to France and into the hands of the Nazis. Photograph: Ruth Hofshi/Alamy Stock Photo

The point of the cities Benjamin loved, by contrast, was that they broke through physical, ethnic and class barriers. In Marseille, Naples and Moscow, life was not a private commodity, but "dispersed, porous, commingled". In Naples, about which he wrote with his Latvian lover Asja Lacis, he found private life had been effectively abolished: "What distinguishes Naples from other large cities is something it has in common with the African kraal: each private attitude or act is permeated by streams of communal life. To exist, for the northern European the most private of affairs, is here, as in the kraal, a collective matter." He and Lacis found in Naples that "just as the living room reappears on the street, with chairs, hearth, and altar, so only much more loudly the street migrates into the living room".

In Naples, Benjamin noted with a north European's shock, children are up at all hours. "At midday, they then lie sleeping behind a shop counter or on a stairway. This sleep, which men and women also snatch in shady corners, is therefore not the protected northern sleep. Here, too, there is interpenetration of day and night, noise and peace, outer light and inner darkness, street and home … Poverty has brought about a stretching of frontiers that mirrors the most radiant freedom of thought."

Is Naples today anything like the one that Benjamin and his lover eulogised? The great Italian actor Toni Servillo once told me that what he loved about Naples was that it was the world in miniature. At the time, Servillo was promoting a film called Gorbaciof, set in the Vasto, the city's multi-ethnic district around the main railway station. And what Servillo says remains true: the great port city of Naples attracts so many immigrant communities that it can still be experienced as a messy rebuke to cities that work through de facto ethnic cleansing and social exclusion. Today, there's a Neopolitain walking tour that takes tourists from the Senegalese market in Via Bologna, to mosques in the Pendino district, past Arab pastry shops and African hair salons, to stalls selling Maghreb crafts.

As for Benjamin, his last visit to Marseille was a bitter one. In August 1940, he found the city teeming with refugees terrified of falling into the Gestapo's clutches. He had arrived in Marseille for an appointment at the US consulate, where he was issued with an entry visa for the United States and transit visas for Spain and Portugal.

In mid-September, Benjamin and two refugee acquaintances from Marseille decided to travel to the French countryside near the Spanish border and try to cross the Pyrenees on foot. The myopic, weak-hearted, 48-year-old philosopher made it across the border to the Catalan town of Port Bou, but then learned that the Spanish authorities were likely to return him and his fellow refugees to France – from where, most likely, they would be transferred to concentration camps and murdered.

Benjamin's body was found in a hotel room, and it is generally thought he took a drug overdose. The inscription on his gravestone in Port Bou quotes, in German and Catalan, from one of his last essays, Theses on the Philosophy of History: "There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism."

It's an aphorism that has been interpreted many ways, not least as suggesting that the progress of capitalism was bound up with the rise of fascism. But it also can be interpreted as pertaining to what cities are.

Benjamin didn't live in an era in which the development of new cities often means state-of-the-art golf courses fringed with fig-leaf social housing; leaf-shaped islands for the über rich that can be seen from the international space station; and gated estates expressly designed so residents can experience that same, perilously short-leased mixture of resentment and self-satisfaction that his parents enjoyed a century ago.

Nor, of course, did Benjamin live to see the attempt to purge Marseille of its wickedness. If he had, he would doubtless have seen through the ostensible civilisation to the barbarism beneath.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion