Reassure me it’s like this for you too: you experience the unexpected—a psychic shock, a physical blow, a realization so disagreeable it sets you reeling—yet even as this event takes place in all its random spontaneity, it’s shadowed by the thought: I should’ve anticipated it. Moreover, it—the shock, that is—should’ve anticipated me; by which I mean to express this notion: in our confusion, we try to reinterpret the experience so as to assimilate it into the ever-evolving narrative of our conscious lives, to make it something that has happened to a self-aware and thinking I, rather than to an inchoate and amorphous swirl of semiconsciousnesses. And in the light of this equally arresting après-coup, the shock becomes a belated harbinger of itself. As one might put it phatically, shaking one’s ringing head, “shit happens,” including effects that should’ve preceded their causes.

I want to write about trauma, and that is why I’m asking you, the reader, to identify with me at the outset. Not, I hasten to add, because I require your empathy for ethical reasons. It is easy to sleep on another man’s wound, as the old Irish proverb has it, and the discourses surrounding trauma all too easily default to this position at the individual level, while at the collective one they all too often raise their explanatory edifices on the high moral ground of other people’s suffering. No, I require your empathy in this strict sense: I want you to locate that response to even a mild shock securely in your own being. For how can we begin to understand the enormous role that trauma has come to occupy in people’s understanding of who—and, yet more pertinently, how—they are, without interrogating our own experience?

By “trauma,” I mean in part the cluster of symptoms defined by the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—to wit, “marked physiological reactions to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s),” combined with an avoidance of “memories, thoughts, or feelings about” or “external reminders” of the events and an “inability to remember” key features of them. More generally, I mean the idea that certain species of experience have the ability to injure us in lasting ways, such that we carry the wound—and, indeed, the experience itself—forever with us, often without our even knowing—the not-knowing being in fact one of the ways we’ve been wounded—until the hurt is reactivated by some thematically related cue. Most fundamentally, I mean the common assumption that psychological experiences can be physically injurious, that “the body keeps the score,” as the title of the most popular book on the subject has it.

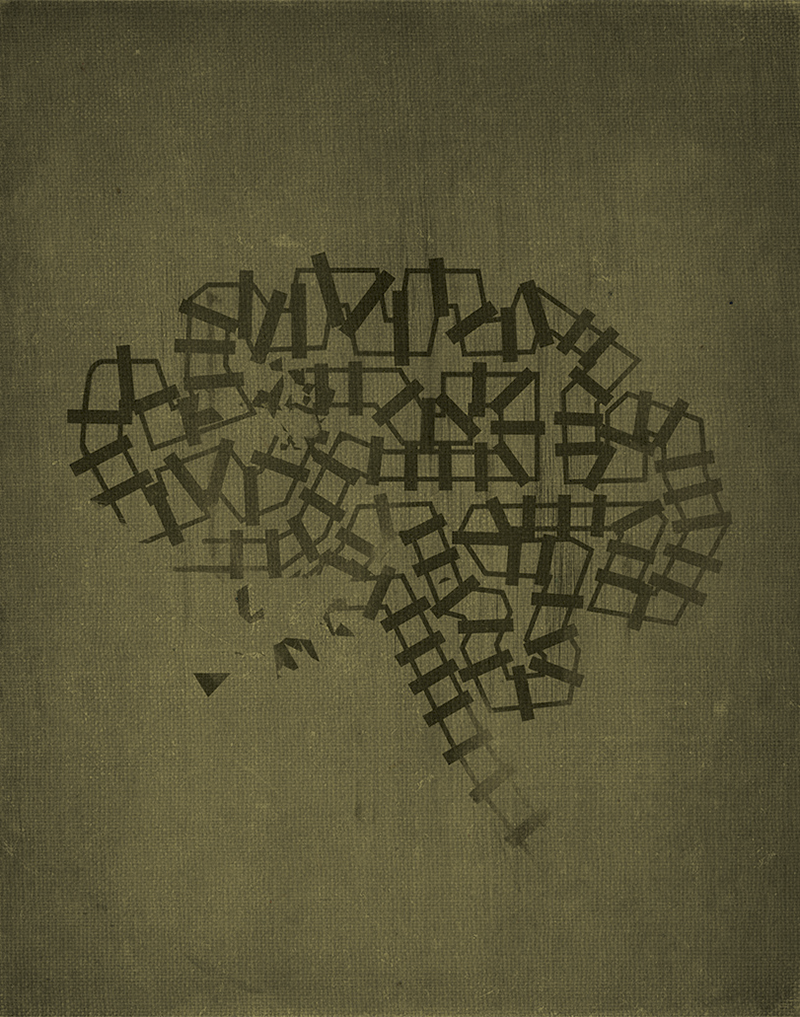

We tend to think of the ability to be wounded in this way as a permanent feature of human experience, albeit one that was long undertheorized. In this way, it is analogous to a psychopathology such as schizophrenia, which we retrospectively recognize as having operated long before it was properly identified. In contrast, I shall be advancing the heretical notion that trauma as we now understand it is not a timeless phenomenon that has affected people in different cultures and at different times in much the same way, but is to a hitherto unacknowledged extent a function of modernity in all its shocking suddenness. Furthermore, I will argue that trauma is so widespread precisely because of the ubiquity of traumatogenic technologies in our societies: those of specularity and acceleration, which render us simultaneously unreflective and frenetic. On this analysis, the symptoms deemed evidence of PTSD are in fact only an extreme version of a distinctively modern consciousness.

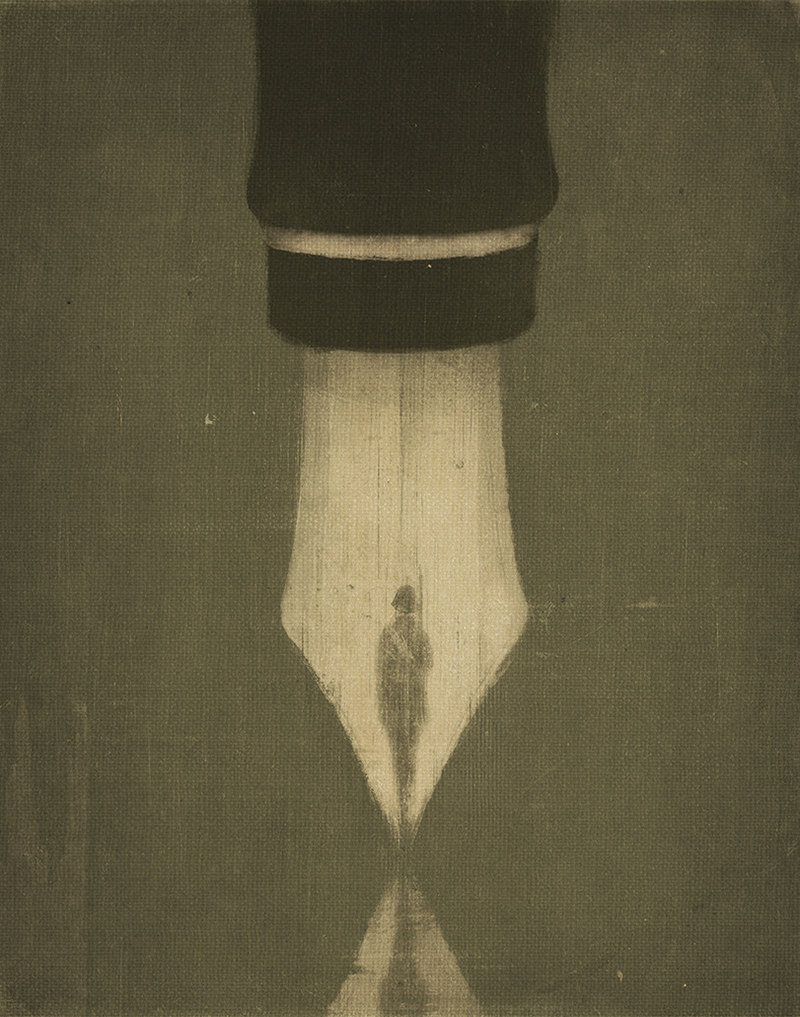

Looked at from a certain angle—like an anamorphic skull—this essay is concerned with literary criticism. That fact will seem strange to those not already familiar with the history of trauma theory, which originated in the work of psychiatric clinicians but reached a far wider public through academics in the humanities. I want to tell the story of how theories of textual interpretation dreamed up in the obscurity of the academy have bodied forth to sustain a novel conception of the traumas humans suffer, a conception as tendentious as the conviction that Jesus Christ died on the cross to redeem our sins. Indeed, part of what gives modern trauma theory its appeal is precisely its covert importation of Judeo-Christian redemptive eschatology: a grand narrative of human moral progress in which suffering is an essential motivation for all the principal actors. For literary theorists, psychic trauma is an exclusive sort of stigmata, a wound at once invisible and sacred, the bearers of which become sanctified and thereby able to convey the singular Truth that shines through the miasma of contemporary moral relativism: that of their own suffering. This suffering is elicited by the intercession of qualified (or ordained) critics and psychotherapists, who join in this communion of pain and distress, and share it with the laity via books and monographs.

Scholarly publications disguise this fundamentally religious (and hence speculative) character in the garb of hard science, enacting modish “interdisciplinary” studies that can be reciprocally employed by those neuro- and cognitive scientists who also seek the desiderata of contemporary academic life: relevance and impact, as calculated algorithmically by the aggregation of readers and references. Not to suggest that this is merely a specialist and recondite affair: Bessel van der Kolk, whose psychiatric work with trauma victims is predicated on the idea that neuroimaging can identify an objective physiological correlate to psychic distress, is one such semi-hard scientist. His 2014 book, the aforementioned The Body Keeps the Score, has been an enormous bestseller in the Anglosphere, and his chapter in Cathy Caruth’s 1995 anthology, Trauma: Explorations in Memory, forms the structural pivot around which trauma theory revolves. Now a professor of English and comparative literature at Cornell, Caruth is the doyenne of literary trauma theory, the person who first identified the “peculiar and paradoxical experience of trauma” as a way out of the ethical and political cul-de-sac of poststructuralism and deconstruction, and who in the process turned van der Kolk’s clinical work with victims of abuse into something like a universal theory of human experience.

How did a bowdlerized rendering of a marginal psychological pathology come to hold such sway in the humanities—and increasingly in popular discourse as well? To answer this question, we need to think as much in genealogical terms as schematic ones. Critics and exponents of trauma theory alike are equally taken by the oddity that no mere causal explanation of trauma’s nature as either an individual or collective phenomenon seems possible. Indeed, the very experience of trauma itself seems to confound causality. But the acknowledgment that traumatic reactions may be immanent in modernity itself, would, I believe, allow for fuller comprehension.

And so we commence our search for the cultural significance of trauma not on the Freudian chaise, but with the nineteenth-century concept of “railway spine.” For it is with the arrival of the train that the phenomenon eventually termed PTSD steams into view. The initiation of railway passenger service in the early decades of the nineteenth century was met with amazement and anxiety in equal measure: people felt themselves to be shot through space and time while also experiencing a profound uneasiness. Accidents were common and widely reported. Crucially, passengers felt powerless, confronted with a technology over which they had no obvious means of control.

Here it should be noted another change that trains carried with them: the enforced harmonization of hitherto different temporalities—clock time, reciprocally required so that these unprecedented vehicles might run on it quite as much as on rails. With its infinitesimal divisions of a notionally continuous flow, clock time brought to the surface of collective consciousness those Eleatic paradoxes heretofore the concern only of philosophers and mathematicians. These divisions separate us again and again from the unbroken unfolding of subjective experience; the individual apprehension of being-in-time—what the philosopher Henri Bergson termed “durée”—is continually being derailed by the imposition of incremental time.

Yet by the last quarter of the century, railways had become sufficiently ubiquitous that their passengers were blasé enough to bury themselves in newspapers and magazines—the relatively novel forms of reading material that proliferated precisely to ameliorate their equally novel ennui. But once humans traveling in this manner exhibited the automatism of the technology itself, any interruption entailed a catastrophic return of the anxiety initially repressed. Wolfgang Schivelbusch, the great theorist of industrialization, puts it thus:

The more civilized the schedule and the more efficient the technology, the more catastrophic its destruction when it collapses. There is an exact ratio between the level of the technology with which nature is controlled, and the degree of severity of its accidents.

I’ll return to this “exact ratio” later, but for now we can note that the very notion of the “accident”—not an unlucky coincidence, such as being struck by a hurricane, but rather a wholesale collapse of a functioning system—also owes its inception to the technologies of the era. These were technical apparatuses capable of self-destruction, and it would seem that the human apparatus was similarly affected: many victims who appeared to have suffered minor injuries—or none at all—succumbed nonetheless to psychic and physical symptoms that proved highly debilitating, if not fatal.

The hedging of personal and corporate liability by means of insurance—what Arthur Schopenhauer described as “a public sacrifice made on the altar of anxiety”—is also a product of the second industrial revolution. In order for some claimants to be compensated, they needed an etiology that allowed for physical causes to produce only psychic effects. Just as traumatized Vietnam veterans and activists would campaign to have their psychological symptoms recognized to qualify for compensation, victims of railway accidents made a similar case to insurance companies. Both groups faced the same problem: Without evidence of organic damage, how could they prove a particular event had so grievously affected them? The initial explanation of the psychic injury suffered by some railway-accident victims was indeed physiological: “railway spine” consisted of supposed microscopic deterioration of the spinal cord caused by the accident’s impact, a physical trauma that had psychic effects.

These were the sort of effects that Charles Dickens suffered when he survived a railway accident in June 1865; seemingly unhurt, he hurried to help those who’d been injured. However, when he was recounting the incident in a letter a few days later, symptoms arose: “But in writing these scanty words of recollection I feel the shake and I am obliged to stop.” Which he did, abruptly, with the appropriate valediction: “Ever faithfully, Charles Dickens.” This is apposite, I think, because it’s the fidelity of recollection that becomes the most important issue for those struggling to establish an etiology of psychological trauma. There was “the shake,” and there was the memory of what provoked it: a cause that, since it was too extreme to be assimilated at the time, becomes a strange sort of effect by recurring in the victim’s psyche, often in the form of day- or nightmares.

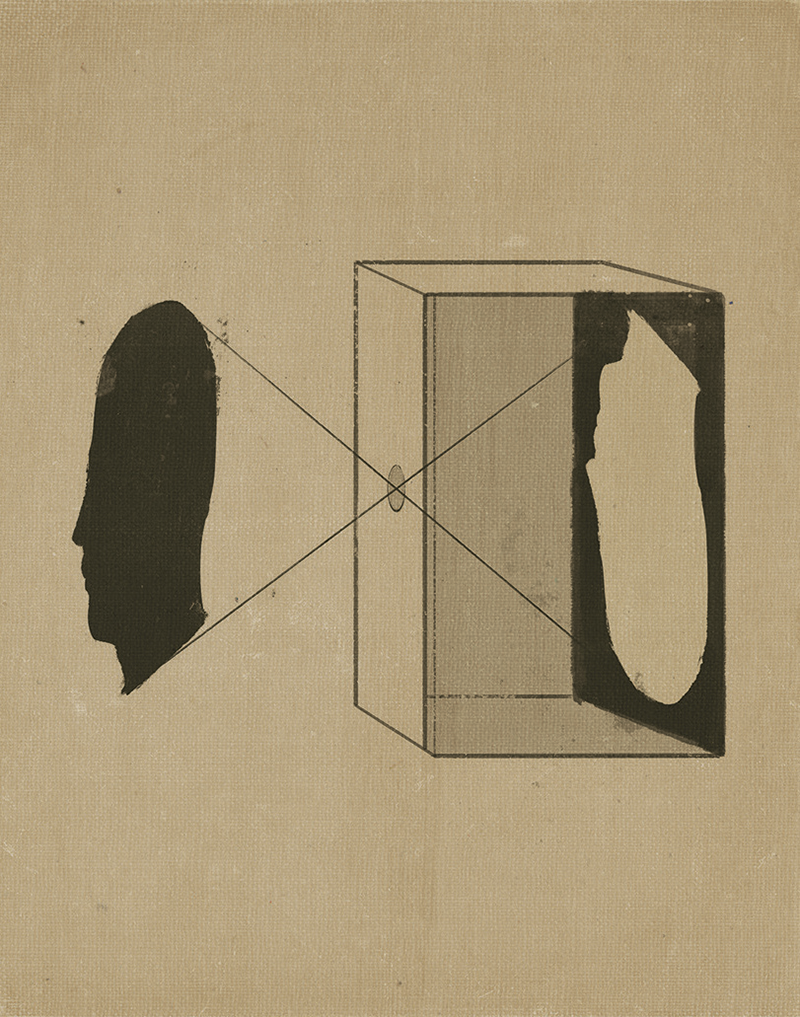

It is as if Dickens’s psyche was so overwhelmed that he was unable to place the experience in a temporal framework—one that would allow him to make a narrative of it, so as to render him once more the teller of his own tale, rather than the plaything of fate. Which is surely what we all want to be, whether we’re novelists or not. It’s this incapacity for proper retrospection—part of the “post” that gets appended to traumatic symptoms—that chimes so obviously with Freud’s notion of Nachträglichkeit, generally translated as “belatedness.” That shocking events could be repressed only to return tricked out in a new guise became one of the conceptual building blocks of Freudian theory during the decades following the codification of the new maladies associated with railway accidents.

The idea that an entirely veridical memory of an event must in some sense remain encrypted in the individual’s psyche was already a fixture of nineteenth-century mnemonic theory, but the general understanding of the form that memory might take was framed in terms of metaphors derived from the emergent technologies of the era. Thus the railway made its appearance as a means of conceiving the traffic between consciousness and memory: “Trains of thought are continually passing to and fro, from the light into the dark, and back from the dark into the light,” the journalist and literary critic E. S. Dallas wrote in 1867. On board were the memories of shocking events—ones that individuals under hypnosis became capable of not simply summoning up, but acting out in exhaustive detail.

The rise of specular technologies in the early nineteenth century, beginning with dioramas and magic lantern shows and culminating in the first photographs made by Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, and others in the first half of the nineteenth century, inasmuch as they presented scenes and individuals within those scenes with apparent objectivity, paradoxically also reinforced the irredeemably subjective character of perception. Their first viewers experienced a sort of frisson on regarding these early photographs—concentrating not on an entire image but the details it revealed of humdrum objects—and would stare at a silver-backed hairbrush, or a crystal glass that they had long known but that had now been re-realized. For Schivelbusch, the photograph offered the sensuous engagement with the immediate foreground that the blurred view from the train had deprived its passengers of. This is another form of the compensatory technological dyad noted by Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents, where he observed that “if there were no railway to overcome distances, my child would never have left his hometown, and I should not need the telephone in order to hear his voice.” A dyad that’s surely congruent with that “exact ratio” which threatens us as we disregard our fears about the technologies we profligately employ. After all, if the phone line were to be suddenly cut off, doubtless Papa Sigmund would feel at once desolated by the absence he had once experienced as routine.

For Walter Benjamin, however, the compensatory mechanism was less reliable and the taking of photographs was itself a form of trauma: “A touch of the finger now sufficed to fix an event for an unlimited period of time. The camera gave the moment a posthumous shock, as it were.” And just as the arrival of the image taken in such a manner was belated, so the entire process of photography could be seen as not simply analogous, but functionally congruent with Freud’s emergent theory of trauma, which in his classic paper Beyond the Pleasure Principle limned the incontinent nightmares of so-called shell-shocked soldiers like so: “The dreams are attempts at restoring control of the stimuli by developing apprehension, the pretermission of which caused the traumatic neurosis.”

The statement can be adapted to speak of photography’s epistemic impact: Images of this kind endeavor to produce objectivity retroactively, by showing the overall context, the omission of which is the cause of subjectivity. This applies to all the specular technologies spawned in photography’s wake—right down to the MRIs and ultrasounds of our frantically medicalized era. These scans produce an odd sort of frisson in us when we contemplate their ghostly images, presented to us as objective representations of our own irredeemably subjective experience, including—some assert—the traumas inflicted upon us.

Looked at this way, the symptoms associated with modern conceptions of trauma are the psychic correlates of physical processes to which the individual psyche cannot consciously adapt: you either repress the posthumous shock engendered by the totality of the camera’s image, or you rise up giddily into psychosis. You either repress your awareness of the steely wheels slicing away within inches of your vulnerable body, or you collapse into catatonia.

The argument that something like PTSD existed prior to industrialization must be sustained with evidence of symptoms constitutive of the modern definition. In her foundational monograph on trauma theory, Cathy Caruth offers the most general definition of trauma as

an overwhelming experience of sudden, or catastrophic events, in which the response to the event occurs in the often delayed, uncontrolled repetitive appearance of hallucinations and other intrusive phenomena.

This last term seems an ambiguous catchall. The DSM-V adds some detail, initially characterizing the mnemonic effects of trauma as “recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s).” It then moves on to the nightmares that so piqued Freud’s interest, and led him to alter his previous contention that all dreams were wish fulfillments: “Recurrent distressing dreams in which the content and/or affect of the dream are related to the traumatic event(s).” Whether or not the manifest content of these dreams (following the Freudian distinction) is synonymous with the traumatizing event becomes, paradoxically, a matter of just that capacity for recall that has been thrown into doubt by the initial amnesia the event induced. The traumatized psyche seems to be being figured, if unconsciously, in a synecdochic relation to the mass-produced trauma of the twentieth century: a part of a whole that finds its collective memories—of the Holocaust, of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—ever more mercurially subjective, even as technological advances seem to ensure their objective representation for all time.

But however the traumatic event is visited on the individual, the question remains: Are the symptoms that have come to be identified as evidence of trauma peculiar to the modern era? We would expect literary critics who insist otherwise to produce evidence from literary sources—either diaristic or fictive accounts of those characteristic flashbacks to events that cannot be narrated in a conventional way. Yet this is seldom the way they go about things. Take, for instance, the opening lines of The Routledge Companion to Literature and Trauma, which was published last year:

A trauma originally referred to a physical injury requiring medical treatment. It derives from the Ancient Greek word for “wound” (τραυμα, traûma). However, since the nineteenth century the term has mutated so that it is now primarily used to describe emotional wounds, traces left on the mind by catastrophic, painful events.

You don’t need to be a semiotician, let alone a deconstructionist literary critic, to observe that these sentences beg far more questions than they answer while assuming much more than can be proved. They say that “the term has mutated” and that it is now “primarily used to describe” something other than it did before. But they leave unsaid whether the wounds now being described existed before the mutation. That greater interest should be shown in semantics than in the reality of the underlying phenomenon that language seeks to capture has, of course, become typical of the field. The nineteenth-century Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure inaugurated structuralism with his theory of meaning—in social structures as much as languages—as a sort of snapshot: a framing of the relationship between signifier and signified within a highly relativistic but nonetheless determinate moment. And with the advent of the philosopher and literary theorist Jacques Derrida, whose name is littered throughout the Routledge collection, the differences that generate meaning became différance, the term he coined to express the notion that by reason of each current signifier being coupled to all the signifiers of the past, each takes its place in a great, clunking train of meaning that’s always in danger of arriving too early, too late, or being altogether derailed.

This diachronic understanding of meaning was figured, by Derrida, as wholly destructive of the Western Logos and its preoccupation with determinate truths about a determinate world, which is why the use of his deconstructive critical methods by trauma theorists—the identification of aporia and paradox in literary texts to radically reinterpret them—for the purpose of constructing a new kind of transcendental signification is absurd not only philosophically, but morally as well. Nonetheless, these theorists are only following their maître: they are willing to say something about the difference over time in trauma’s meaning so conceived, but nothing at all about what it is that’s being signified.

Just as early psychological theorists of trauma were preoccupied by the way traumatic experiences seemed to confuse the possibility of wholly truthful recall, so these literary theorists of trauma are obsessed (and I don’t believe this is too strong) with the way their understanding of semantics confuses the possibility not just of trauma’s effective representation but of any effective representation at all. This presumably explains, in part, why they scarcely attempt to find such representations. At the outset of Nicole Sütterlin’s essay for the Routledge collection, titled “History of Trauma Theory,” she writes that

isolated examples of what today we refer to as psychological trauma can arguably be traced all the way back to Homer’s Iliad. Insofar as tragic events have caused humans immense and prolonged suffering since times immemorial, trauma may be deemed an “anthropological constant.”

The important modifiers here (and they’re ones that haven’t changed their significance much over the years) are “arguably” and “may.” Elsewhere in the literature of trauma theory, there are equally cursory references to descriptions of trauma that may conform to the symptoms listed in the DSM. We are told that it is present in the Epic of Gilgamesh, or the classical authors, or in Shakespeare. This latter attribution I find the most interesting. Standing on the brink of modernity, Shakespeare’s oeuvre is all-encompassing: love and hate, pain and pleasure, joy and despair. Truly, all of human life is present in his plays and poetry. A number of theorists have argued that Shakespeare’s Macbeth is a victim of trauma, and they would presumably see this at work in his most celebrated soliloquy:

Is this a dagger which I see before me, the handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressèd brain?

We can agree that Macbeth is tormented by visions, and that these visions relate to psychic content formed by an event he is incapable of factoring into his own self-consciousness; but unfortunately for trauma theorists, his murder of King Duncan lies in the future, rather than being an unassimilable element of the past.

Equally, Hamlet may be visited by the ghost of his father, whose apparition corresponds, in its very ontological instability, to his repressed awareness of his father’s murderer’s identity, but nowhere does Shakespeare describe him as troubled by memories that he cannot square with his sense of himself. Rather, it is his divided nature itself that is figured as primary. Once more it is “conscience [that] does make cowards of us all.”

A further example of wishful exegetical thinking can be found in readings of Sophocles’ early tragedy Ajax. Bessel van der Kolk informs us that the play has been performed more than two hundred times for U.S. veterans, who have found its depiction of a great warrior driven to madness and suicide easy to identify with.

I have no doubt that Ajax speaks to recent combat veterans, but as is the case with much of Greek tragedy, the play is actually about the universal predicament of the human psyche, forever balletically poised between fate and freedom. Ajax is a perpetrator rather than an innocent victim: one who, crazed by hubris, slaughters men and animals indiscriminately because he feels himself slighted. His suicide is a function of humiliation—not trauma as understood in the contemporary sense at all. Following stagings of Ajax, according to van der Kolk,

many [of the veterans] quoted lines from the play as they spoke about their sleepless nights, drug addiction, and alienation from their families. The atmosphere was electric, and afterward the audience huddled in the foyer, some holding each other and crying, others in deep sorrow.

It’s an affecting portrayal, until you stop to consider that it has been provoked by the plight of a man who goes mad merely because the dead hero Achilles’ armor has been awarded to Odysseus rather than him, because Odysseus is judged to be the better warrior. This is the vainglory of Hotspur—another of Shakespeare’s characters whose tribulations are often interpreted as PTSD—raised to the power of a hundred, and the Nachträglichkeit here is the belated recognition of Ajax’ committal of an atrocity. It’s not hard to see why this perpetrator-friendly approach might appeal to the U.S. military in particular: the wars undertaken since September 11 have pitted overwhelming firepower against lightly armed guerrilla forces, to devastating effect. It’s the goddess Athena who diverts Ajax’ homicidal rage away from Agamemnon and Menelaus, the leaders of the Greeks who he feels have snubbed him, and redirects it toward the livestock they have taken as booty from the Trojans. In this induced trance he indiscriminately slaughters sheep, goats, cows, and humble herdsmen. It’s a nice analogy of asymmetrical modern warfare.

Van der Kolk tacitly demonstrates his exemplary patriotism by refusing to make any moral judgments about veterans afflicted with PTSD. Discussing a form of exposure treatment whereby veterans are repeatedly subjected to representations of their own traumatizing events in order to desensitize them, he remarks:

One form . . . is virtual-reality therapy in which veterans wear high-tech goggles that make it possible to refight the Battle of Fallujah in lifelike detail . . . As far as I know the U.S. Marines performed very well in combat, the problem is that they cannot tolerate being at home.

What a Pandora’s box is opened by that chilling little aside: “As far as I know.” Performing “very well” for this guru of trauma therapy (the founder of one of the most influential research centers on the malady in the United States, no less) is reducing a city to rubble using depleted uranium shells and then incinerating enemy combatants and civilians alike.

But it may be that such validation is therapeutically necessary. At least one explanation for the widespread suffering from what was first dubbed “shell shock” (and then placed under the causational catchall “war neuroses”) was that the mass conscript armies of World War I returned to take up social roles that afforded no valorization of their disturbing experiences—no Ajaxes, they. In earlier eras, career warriors were not only permitted to describe their bloody feats and failures but were part of a wider culture that effectively encouraged them to do so, or sustained others to do so using the appropriate poetic forms. Moreover, conscripts returning from the war had to reassume civilian identities, thus introducing a troubling doubling of their own psyches: such extraordinary memories were quite simply unassimilable by their quotidian minds.

For Paul Fussell—who, as a literary critic and a former U.S. Army officer and Purple Heart recipient, certainly knew what he was talking about—the ironic reversal enacted between August 1914, when the armies of the great European powers marched off to war, drums beating, and August 1915, by which time they were bogged down in horrific trench warfare, is the affective crucible of the twentieth century: out of this living hell comes our sense of absurdity, of detachment, and yes, of trauma. Fussell’s groundbreaking study, The Great War and Modern Memory, hypothesized that trauma was collective and largely involuntary. He also saw it as a hermeneutic crisis: in the packs of British soldiers—officers and enlisted men alike, for this was quite likely the first fully literate army to enter the field—were copies of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress and The Oxford Book of English Verse, uniting them in an imaginary realm of organic social relations and bucolic beauty. Then they got out their spades and trowels and began to dig in. The howitzer shells that screamed down upon their heads left little time for textual interpretation, but one thing that became painfully clear was that never before had the ideal been so at the mercy of the real.

While World War I may have been the first fought by fully literate armies, World War II was fought by Allied forces that came equipped with their own psychiatrists. Such was the extent of battlefield trauma during the D-Day landings that the U.S. Army’s emergency field hospitals had to be staffed with psychiatrists to treat soldiers suffering from no discernible bodily injury yet manifesting the most florid of mental symptoms—a truth not simply inconvenient for the emergent world hegemon of the postwar period, but inadmissible. So trauma sank back down into the collective unconscious once more, only to reemerge after a defeat inflicted on U.S. forces that—because of all the asymmetries of force and culture involved—couldn’t be repressed. That the traumas experienced by Vietnam veterans were as much a function of acts they had perpetrated as they were of those inflicted upon them in part explains why contemporary trauma theorists’ conceptions of the malady, and their attendant therapies, collapse this fundamental ethical distinction. Significantly, van der Kolk’s attempts to treat a Marine veteran who had raped a Vietnamese woman and murdered several civilians, children among them, is the first of his transformative case histories related in The Body Keeps the Score.

A quintessential early example of the workings of war neurosis is Erich Maria Remarque’s account of the post hoc symptoms that visited him prior to his writing of All Quiet on the Western Front. For a decade after the war he’d scarcely thought about the battlefield, and he’d concentrated his literary efforts on the journalism that was his daily bread. Then, afflicted with anxiety and depression, Remarque realized that he had been repressing memories of his wartime experience. The autobiographical novel he then completed in just a few weeks is both vivid and lurid, a succession of images impressed on his young psyche by the extreme violence and destruction of newly mechanized warfare, seemingly transferred directly to the page after a decade-long hiatus.

As it was with Remarque, so it was for R. C. Sherriff, whose play Journey’s End—which places shell shock at its dramatic center—was staged the same year, 1928, as the former’s novel was published. Both stood in a synecdochic relation to societies that had collectively repressed their experience of the war. I would argue it was this mass experience of Nachträglichkeit that influenced Freud’s pivot, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, back to a view of trauma as having an organic basis: whatever else the death drive may be, it’s clearly innate. Freud’s recognition of the death instinct also seemed to confirm his earliest intuitions that his hysterical patients really had been sexually abused. For Freud, the human organism is propelled toward even unpleasant experiences if they conform with its instinctive desires; moreover, the replaying of awful happenings at the front not only registers the amplitude of said desires, but also confirms the truth of these experiences.

That Freud beat Remarque and Sherriff to the punch is unsurprising. Already steeped in the phenomena associated with hysteria, including its simulation—or mirroring—in the state of hypnosis, he was primed to understand war neuroses as another response to a catastrophic breakdown in the psyche’s assumption of stability and continuity.

Freud’s later abandonment of the physical actualité underlying his patients’ hysteria ultimately allowed the whole edifice of Freudianism to come under assault—from within by the erstwhile Freud Museum archivist, Jeffrey Masson, and from without by feminist thinkers who saw in it a willful (and very masculine) determination to obviate women’s suffering at the hands of men; this, and his equally tendentious identification of the representative human psyche as male.

In her foundational 1991 essay, “Unclaimed Experience: Trauma and the Possibility of History,” Caruth exonerates Freud for some of his theoretical waywardness on the basis that he, too, is a victim of trauma, his forcible expulsion from Vienna by the Nazis being encrypted in the essay’s repetitions and caesuras. Caruth’s determination to cleave simultaneously to the idea both that the traumatic memory is the only historic fact the individual possesses and that this facticity remains incapable of adequate representation is paradoxical bordering on the perverse. By the same analysis, what de-individuates us in relation to the historical eras we inhabit is precisely this: the shocking and therefore inassimilable nature of the traumatogenic events to which we’ve been subjected.

For Caruth, then, trauma jumps the rails of subjective sense to become not a marker of individual repression but the die stamped by history on the human psyche. This theoretical view has in turn been integrated into the clinic: the most recent update to the DSM has made PTSD a possible diagnosis not just for those who have experienced traumatic events “directly,” but also those who have learned about traumatic events suffered by others. Meanwhile there is a growing appreciation for “transgenerational” trauma, in which trauma induces epigenetic changes inheritable by children. And so trauma becomes a collective experience that enjoins a collective to come together so as to bear witness to . . . well, what? Is theirs to be a common destiny or a common suffering? Or quite possibly both, interdependently? The paradox is that Caruth and the other trauma theorists who follow in her vein wish to assert trauma’s significance as timeless, all while forging an ideology clearly linked to the most salient mass traumas of the twentieth century. Or at least to one in particular: the Holocaust. In fact, one of the most significant trauma theorists, the Israeli-American psychiatrist Dori Laub, was himself a Holocaust survivor, which undoubtedly gives his theorizing moral traction—but that’s no reason to accord his epistemological claims any greater status than those of anyone else.

Or is it? The crisis in American literary criticism is often figured as being peculiarly personal as well as political. Derridean deconstruction was introduced into American letters by the émigré critic Paul de Man. The posthumous revelations of de Man’s Nazi collaboration seemed to fatally elide the philosophic and the practical: here was a man who had inculcated in Yale literature students (Caruth among them) a view not only of language as detached from its object, but of its users as condemned to ignorance of their own meanings in the very act of utterance. A view de Man’s acolytes then marshaled in defense of his anti-Semitic wartime writing.

Setting aside the straw man that is de Man, what we have here is surely as much a crisis in professionalism as it is in ethics. Without being able to say anything definitive about literature, what, pray, is the point of literary critics? Concomitantly, if such luminaries lay claim to the artistic freedom allotted to poets and novelists, then why are their texts all too often devoid of any aesthetic sense at all, while being replete with jargon both ugly and incomprehensible? Heading in the opposite direction, the breaking down of barriers altogether between discourses and the view of literature as possessing the epistemic gravity of philosophy—or science for that matter—also seem to have produced still more critical texts that exhibit the worst stylistic failings of both. We find in the trauma theorists’ offerings little of the playfulness and rhetorical flair that marked the eruption of Barthes and Derrida onto the scene.

Certainly not in the work of Caruth, whose academic papers sometimes foreground the direct testimony of the traumatized—whether they be Holocaust survivors or African-American teenagers who’ve witnessed the gunshot killings of their peers—seemingly as a guarantor of their authenticity, for this transfer of utterance back into graphology reverses the devilishness of deconstruction and returns literary critics to the side of the angels. No longer priestesses and priests in the cult of the Western Logos, no longer implicit defenders of the status quo ante, literary critics become warriors for synchronic justice conceived as catharsis. All must be resolved now by collective abreaction, whereby literary critics will be the handmaidens of a sort of universal truth-and-reconciliation event: cathartic Rapture. It calls to mind Kafka’s teasing dismissal of all such year zeros in The Zürau Aphorisms:

The decisive moment of human development is continually at hand. That is why those movements of revolutionary thought that declare everything preceding to be an irrelevance are correct—because as yet nothing has happened.

If the distinguishing feature of traumatic memory is that it both defines and even determines the being and doing of the rememberer—his fear and his trembling—then that of normal, healthy memory is that it serves the needs of the present. This, of course, doesn’t guarantee that “normal, healthy” memory is necessarily more accurate than its traumatic sibling; after all, the psyche tends to operate by associations of ideas that are inherently selective. As Nietzsche so succinctly puts it: “ ‘I have done that,’ says my memory. ‘I cannot have done that,’ says my pride, and remains inexorable. Eventually—memory yields.” Regarded this way, “normal” memory is inevitably self-seeking. The nationalist myths that dominate memories of war, even in the era of conscript armies, are examples of self-serving at a collective level—but there are many, many others.

The definition of PTSD that appeared in the DSM-IV was weighted in terms of its etiology and symptoms rather than its progress or outcome. The current edition follows this rubric by stating that PTSD is produced by certain sorts of experiences, and itemizes them: “Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence.” But how the manner of this exposure—direct, indirect, or representational—effects severity remains a matter of profound dispute. Some trauma theorists embrace the bizarre notion that it’s actually the secondary witness who receives the trauma in its truest form—because the primary victim cannot, according to them, fully recall the experience.

The similarity between the family tree of trauma and that of humanity itself cannot be ignored: in both—and in contradistinction to those of other species as a rule—initial diversity is pruned away until only one exemplar remains. However, down the generations of trauma theorists, there have, of course, been numerous black sheep. One such mutation—predictably repressed by the trauma theorists themselves—was expressed in the Eighties, when so-called recovered memory syndrome coupled with multiple personality disorder to create an extraordinary popular delusion: the widespread conviction that an extensive network of satanic covens existed throughout the United States (and to some extent in the United Kingdom, although notably hardly anywhere else in the world) dedicated to the sexual abuse and ritual sacrifice of thousands of children.

This outbreak of mass hysteria shared with trauma theory the underlying conviction that the recall of trauma could be delayed, even by years and decades, and that its authenticity was guaranteed by its own belatedness. Uncorrupted by interlocution (which would necessarily entail confabulation), the victim retained an absolutely reliable memory of whatever satanism they’d been subjected to—such as the bloody pentagram being inscribed and the naked, chanting figures wearing animal masks forming a circle around them. To collapse the Marxian dialectic of premature revolution: this was history simultaneously as tragedy and farce. By reason of these recovered memories, the falsely accused suffered and their discredited accusers suffered as well (from a bespoke new pathology of “false memory syndrome”), while behind this particular scrim, the real actions that had projected such exaggerated images continued: long-term, systemic sexual abuse of children in a whole range of institutions, including orphanages, churches, and schools; abuse that has come to light in subsequent decades—not, it seems important to note, because of any evolution in our understanding of human memory, but simply because of the gradual accretion of perfectly traditional forms of evidence: the eyewitness testimony of the abused.

The discrediting of satanic ritual abuse was concurrent with its exposure. Writing an investigative piece on the subject myself in the early Nineties, I was told by the then head of the children’s services section of Britain’s National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children that while the incidence of such ritual practices was vanishingly rare, commonplace (!) sexual abuse was very likely far more widespread than anyone was publicly prepared to admit. The subsequent “forgetting” of the entire episode—at least in the evanescent realm of popular consciousness—can be considered analogous to other caesuras in the genealogy of trauma.

But of course, anxieties about the extent to which the symptoms of trauma—the flashbacks, daymares, nightmares, shakes, and shivers—have been implanted in distressed minds by well-meaning but wrongheaded doctors can never be entirely repressed. The problem being that for the traumatized there is no external, open wound—only an internal, psychic one. As Caruth puts it:

The possibility that reference is indirect, and that consequently we may not have direct access to others’, or even our own, histories, seems to imply the impossibility of any access to other cultures, and hence of any means of making political or ethical judgments.

But behind all of this sleeping on the other’s wounds lies the godless father of all postmodernists, bristling with his own ressentiment while mordantly hissing that “eventually—memory yields.”

You wouldn’t necessarily expect an essay on literary forms and their developments—in this case, Walter Benjamin’s “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire”—to touch upon the origin of traumas in their widest sense; and yet it is there that Benjamin writes of Henri Bergson’s theory of memory that it

manages above all to stay clear of that experience from which his own philosophy evolved or, rather, in reaction to which it arose. It was the inhospitable, blinding age of big-scale industrialism. In shutting out this experience the eye perceives an experience of a complementary nature in the form of its spontaneous afterimage, as it were.

Here, under “big-scale industrialism,” one thinks of everything from the showers of sparks produced by a metal lathe to the white-hot stream of steel poured from a crucible, to the bright flash of combined magnesium and chlorate that shocked the rigid sitters as the camera’s eye captured their images for eternity. All around the shaky-shivery coming-into-pathological-being of trauma in the nineteenth century we find these specular images and afterimages, which in themselves are perhaps also conceptual ones. Toward the end of the century, Wilhelm Kühne developed his theory of orthography: the idea that an image can be preserved on the retina. With the contemporary obsession with forensics, orthography came to be taken seriously enough that detectives at murder scenes would, indeed, look into the victims’ eyes, in the hope that the culprit’s image could be beheld there, leading to their rapid arrest and punishment.

This is, I think, the context within which we should view trauma theory. The theorists feel great crimes have been committed but—by reason of the instability of language, and the partiality of those who speak it—there can be no possibility of an indictment. Unless, that is, there is a veridical image imprinted in the victims’ mind/brain, one which can be extracted using a method that depends simultaneously on the necessity of speech and the impossibility of its communicating the truth. The great anxiety about the forgetting of trauma is that we will be doomed to repeat it. Just as we might conceive of the symptoms associated with PTSD as the somatic equivalent of an earworm: an attempt to “play the experience through” to the effective end we were denied in the first instance precisely because of our shock. So it is that we stage one Holocaust Remembrance Day after another, all the while agonizing that if a critical mass of human animals forget their own genocidal potential, this will activate it.

But if there is anything distinctively modern about the Holocaust or Hiroshima, it lies in the technologies that enabled them: the aforementioned railways, communication networks, and of course the most plangent example of a technical apparatus capable of blowing itself to pieces, the nuclear fission bomb. And then there are the particular forms of these events’ specularity: as Susan Sontag observes, following Hannah Arendt, the notorious photographs of Nazi concentration camps were errant to the point of being staged. The piles of naked corpses, and beside them their discarded clothes; the survivors lolling in their bunks, heads obscenely large, bodies grotesquely emaciated—all of this was what the liberators witnessed (and what undoubtedly traumatized many of them—one thinks of Seymour Glass’s suicide in J. D. Salinger’s “A Perfect Day for Bananafish”). But when the camps were operating normally, they were tidy, well-regulated environments in which the killing was handled expeditiously and out of sight.

Reading trauma theorists such as Dori Laub and Shoshana Felman, I’m struck by the common vocabulary of crisis, despite their professional differences as psychoanalyst and literary critic: the crisis of history and the crisis of signification are referred to as interoperable, if not interchangeable. In her essay “Irresponsible Nonsense: An Epistemological and Ethical Critique of Postmodern Trauma Theory,” Anne Rothe, an associate professor at Wayne State University, elegantly debunks the trauma theorists’ claims to have arrived at a new basis for knowledge. She takes aim at Caruth and her co-authors, tasking them with “dispossess[ing] victims and survivors of the subject position of witness in order to ascribe it to themselves and the status of testimony to their self-aggrandizing speculations.”

For Rothe, the elision of the crisis of signification with the aporias and paradoxes that characterize trauma victims’ testimonies has had precisely the inverse effect from what was desired: rather than these terrible memories, individual and collective, being afforded narrative comprehension by their telling, they are transmogrified into psychic virions capable of infecting those who come into contact with their hosts. It is therefore incumbent on those who would bear witness to the great traumas of the twentieth century that they become . . . what? Yes, you guessed it: deconstructing literary critics.

That the Holocaust has such a privileged position in this transmission of trauma lends weight to Rothe’s assertion that the pivot from de Man’s deconstruction to Caruth’s trauma theory is as much an attempt to restore meaningful signification as it is an attempt to base a theory of literary interpretation on its impossibly arbitrary character. In all this tergiversation—much of it, doubtless, at academic conferences where papers are presented and reputations gilded—the result becomes “the nonsensical and unethical transformation of the Holocaust into a rhetorical figure.” In other words, Holocaust Remembrance Day voided of any genuine remembering.

To decouple the experience of the great twentieth-century traumas from the train of history is, paradoxically, to watch it decelerate into a siding and halt. Only the universalization of such traumas and their incorporation into a grand narrative of human moral progress will deliver “us” (itself a dubious piece of inclusion, humans being quite as various as they are) from the suspicion that things are getting worse. Getting worse, specifically, through those technologies of acceleration and specularity that I believe have massively increased the production of trauma. Borges’s Funes—a young man traumatized by his own memory, which is so accurate and complete that it metastasizes into the present—is such an uncanny creation because, of course, he anticipates our own era, in which what I think of as “peak photo” cannot be far off. It’s estimated that 2015 was the first year in which more than a trillion photographs were taken. Soon enough, I wager, we will live through a single day in which more photographs are taken than in the century after Niépce set up his apparatus in Chalon-sur-Saône. And don’t get me started about the closed-circuit surveillance systems that can make it seem we’re breaking the fourth wall of some real-time mass drama every time we speak our lines. We look at screens and through them for most of our days, our only relaxation being the switch from having to click and point for ourselves to being compelled to do so by some clever editor’s crosscutting between shots, which are becoming shorter and shorter in lockstep with our own diminishing attention spans.

I asserted at the outset that I believed human psyches and the specular and accelerating technologies of the past two centuries had entered a sort of symbiotic relationship with one another, each proliferating by means of the other. To paraphrase Freud differently: If there were no mobile phones with built-in cameras and no assemblage of the internet, there would be no requirement for me to visit another town in order to take selfies in front of its landmarks so as to upload them to my social-media feeds. And what is all of this world-girdling reflecting and re-reflecting, if not the compulsions of a collective psyche condemned to remember rather than forget—to remember not the grand narratives of human redemption, but the trauma by a thousand blows that descends on the human psyche by reason of its occupying these sorts of environments? Fast-forward from Benjamin’s posthumous shock a little and we find that

haptic experiences of this kind [are] joined by optic ones, such as are supplied by the advertising pages of a newspaper or the traffic of a big city. Moving through this traffic involves the individual in a series of shocks and collisions. At dangerous intersections, nervous impulses flow through him in rapid succession, like the energy from a battery.

The insistence that technologies of this sort are value-neutral is shown up for the speciousness it is once the cost of their production becomes clear. That we live in affluent societies, in bubbles of safety and comfort underwritten by the labor of machines and people banished from our purview, is a realization everywhere repressed: these are the steely wheels slicing away beneath the most vulnerable portions of our bodies, as we swipe left and the train of progress chunters on into the night. The light of reason shines the way.

Into the crepuscular realm of social media, for example. If we understand trauma to be a function of technologies that engender in us a sense of profound security underscored by high anxiety, then platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok would seem purpose-built for its manufacture, offering as they do the coziness of Marshall McLuhan’s global village and its inevitable social problems: global gossip, global reviling, and global abuse. A recent article in Slate pointed out that on TikTok, any number of behaviors are now dubbed “trauma responses” by the self-styled “coaches” who post videos on the app telling their followers how to identify the trauma within themselves. Many thousands of people are becoming convinced that perfectly ordinary reactions to such commonplace problems as overbearing bosses or perfidious friends are, in fact, reflex responses seared into their psyches by the white heat of trauma, which suggests to me that this medium is indeed its own message. That message is the very antithesis of Wordsworth’s “emotion recollected in tranquility,” namely: being infected with emotion in pandemonium. This epochal social and technological change has indeed involved millions reclining in little pixelated psychic train carriages, powered by mutual affirmation, which from time to time are violently derailed. And yes—there also seems an exact ratio between all those likes . . . and all those hates.

That social media is inherently traumatogenic is thus a truth universally acknowledged—the very names of the sites proclaim it: TikTok evoking the merciless imposition of clock time that severs us, again and again, from our subjective experience and propels us into the savage realm of impersonal quantification. So why not take people at their word, rather than try and rewind the clock to a time when all that was required to comprehend was a dictionary of historical principles? We understand what “shit happens” means because shit does, indeed, keep happening, while our high-tech specular technologies enable us to capture this in slow motion or speed it up, to watch it happen again and again, or interpolate episodes of it happening in the past or the future into our own present. This alone: the formal structural relation between the flashback and the radical analepsis of trauma should surely have alerted us before now to the intrinsically traumatogenic character of the modern era, with its ever more graphic and hyperreal stagings of human disembodiment. Is the witnessing of violence onscreen traumatizing? Not according to the DSM-V, which explicitly denies this—with the exception of those such as police officers and social workers, who may have to view such imagery as part of their work. But then they have to say this, don’t they—for disavowing the entertainment value of violence would be a case of That’s all, folks! We’d collapse into a timorous huddle at the memory of all the meaningless gore we’ve seen.

Reassure me it’s like this for you too: you find yourself coming to consciousness again and again in this world, your mouth open, and speech emerging that seems to be making sense—yet even at the moment this takes place in all its incomprehensibly random spontaneity, it’s shadowed by this thought: I should’ve anticipated it . . . Moreover, it—the language, that is—should’ve anticipated me. By which I mean to express this notion: in our confusion we try to reinterpret the unthinking utterance so as to assimilate it into the ever-evolving narrative of our conscious lives—to make of it something that’s been uttered by a self-aware and thinking I, rather than an inchoate and amorphous swirl of semiconsciousnesses. And in the light of this equally arresting après-coup, the speech becomes a belated harbinger of itself—as one might put it phatically, shaking one’s ringing head, “shit happens,” including thoughts that should’ve preceded their expression.