晚唐五代博物学的知识脉络与亲验传统

文 / 余欣 周金泰

博物之学,其来尚矣。自周秦以降,至《山海经》出而奠定其传统,至魏晋时有《博物志》而日渐成熟,爰及隋唐,已蔚为大观。博物君子体备万物,遐观殊方,博观省思,穷源竟委,究其旨归即在广耳目,通大道。古代中国的博物之学是古人体察万物,摹想世界,认识自然、人类和社会的知识汇集,是传统中国的知识系统构架的基底性要素之一。这样一种“关于物象(外部事物)以及人与物的关系的整体认知、研究范式与心智体验”的知识系统是如何被承载,又是怎样传袭与流布,或者说,博物学知识的集合是怎样吸纳各种不同的知识个体的?倘以《北户录》与唐时已有之甲乙丙丁四部经籍分类试将参比,则能在一特定角度上展示博物学知识在后一种形式载体中的分布。

余欣 周金泰著

商务印书馆,2025年

《北户录》三卷,晚唐人段公路撰,崔龟图注。段公路,东牟(今属山东省)人,段文昌孙,段成式子辈。其传不见史册,唯《新唐书·艺文志》“北户杂录”条下注云“文昌孙”。陆希声《北户录序》称其尝“以事南游五岭间”,其仕宦行迹略见《北户录》载记。注者崔龟图,唯书中结衔作“登仕郎前京兆府参军”,大约为晚唐五代时人,他事无所考。是书成于唐僖宗乾符年间,为公路著录其在岭南闻见的笔记,所载皆岭南风物,草木果蔬虫鱼羽毛之类。后世书家允其博载风土外,尤善其保留了不少后世散佚古籍。

一、六艺钤键:段公路的学识基底

陆希声《北户录序》谓唐人著述传世不多,可由以参详古书崖略的,除去《北堂书钞》《艺文类聚》《初学记》而外,《北户录》也可算一种。书凡五十二条,引征文献几二百种,正文涵涉书篇计一百一十余种,征引频次二百有零,注文所引文献大致在一百四十种、二百九十次上下,述引博洽,蔚然可观。此书所征引书目篇章非唯可借之以管窥古书崖略,其引书情况恰体现了撰者兴致之所至、目力之所及,也正是考察其人知识构成的一个极好维度。今取《北户录》正文所引书类,与《隋书·经籍志》《旧唐书·经籍志》相参较,试做厘析,意在探求段氏“博而且信”的基底所在。

《北户录》引甲部经录文献十六种,计二十八次,又有二《经籍志》所载外《唐韵》一种。其中以《字林》《说文》《尔雅》(《尔雅注》)见引最多。晋吕忱撰《字林》,其“附托许慎《说文》,而案偶章句,隐别古籕奇惑之字,文得正隶,不差篆意”,部类分次仍循《说文》五百四十部,而广为搜罗,增补旧释。上承许氏,下启《玉篇》,至唐时书科举试得以与《说文》并列。从《说文》到《字林》,并及《急就章》《凡将篇》《劝学篇》《小学篇》一类,字形、释义、切音是根本所重。诸家字书,或呈现书法流变渊源,或罗列古今字、正字、异体字、俗字,或注音方式有所改进,或音切载记因地域、时代而有不同,或搜罗范围愈广,或所收字义愈新,代季演变的源流、远近殊俗的土风往往见存此中。识字而以别辨万物,而以概知遐迩,而以通了古今,知识在字书中的层垒,而博物之学也萌发其中。

“夫《尔雅》者,所以通诂训之指归,叙诗人之兴咏,揔绝代之离词,辩同实而殊号者也。”《尔雅》大致成书于战国末年,其编订历经众手,其功用一在通畅古今言语,描摹百物情状,使人明达其意旨,一在总汇训释绝代殊语,使人不至因异代而生隔阂,一在收聚析辨异名而同实的词物,使人了解其本真。嗣后历代多有注疏,就《隋书·经籍志》可见即有樊光、孙炎、沈旋、江漼诸氏,而郭璞注为其中翘楚。非独有音注,郭氏又作《尔雅图》并讃,图、讃虽亡佚,循名以推之,应当是进一步阐释《尔雅》中名物并用图像、韵文形式加以表现的著述,所谓“别为音图,用袪未寤”。凡此种种,其旨归都在令人通达言语,明识物类,故云“若乃可以博物不惑,多识于鸟兽草木之名者,莫近于《尔雅》”,正与前述《说文》《字林》等字书令人博闻广识的功用相类。 《尔雅》今存篇目十九,前三篇《释诂》《释言》《释训》为字书自有的章目,其后十六篇专在训释各类名物,大致可以分为七组:一、《释亲》,明达人伦;二、《释宫》《释器》《释乐》,涵盖生活、技艺诸方面;三、《释天》《释地》《释山》《释水》,训解天地山川;四、《释草》《释木》《释虫》《释鱼》《释鸟》《释兽》《释畜》,叙述草木虫鱼。类目涵及人类、自然和社会,藉篇归类,以类相从,人伦居首,乃其价值内核所在,以生活、技艺承接其次,以天地山川为外郭,草木虫鱼为辅载,而世界图像即便孕育生成。通过分类的方法,而划定出自然、人类、社会各自的位置,使其各居其位,既定其位,也就意味着搭成了认识的构架和世界图像的雏形。博物之学对于世界的构想尽可以有其各不相同的认识与想象,然而其根底必定有这样一个基底性的认识构架来承载。此即《尔雅》一类书目在教人以名物之外,对于中古士人的知识框架所具有的特别意义。

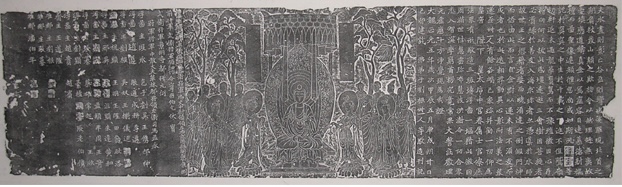

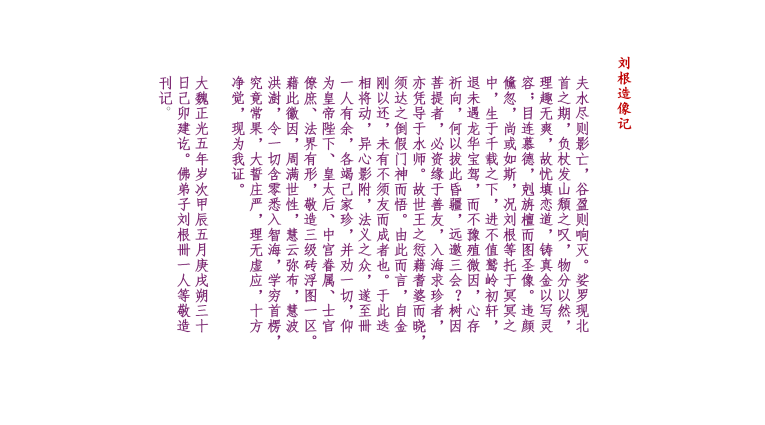

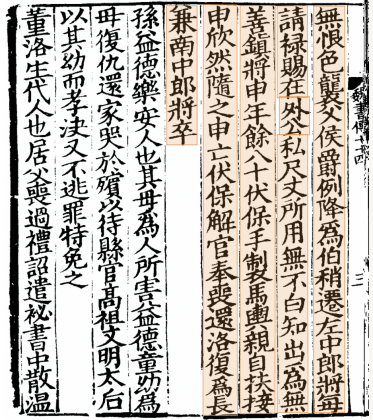

▴

南宋 国子监刊本《尔雅》

台北故宫博物院藏

或云“文字者六艺之宗,王教之始,前人所以垂今,今人所以识古”,郭璞推崇《尔雅》,以为“诚九流之津涉,六艺之钤键,学览者之潭奥,摛翰者之华苑也”。是以博物之学广无涯际,洋洋乎大哉,而诂训、小学可以居摄。

李慈铭《灯下读<尔雅>偶题三绝句》有句云“理学须从识字始”其间旨趣则一。

《北户录》引乙部史录典籍三十一种,约六十二次,不见诸《隋书·经籍志》《旧唐书·经籍志》的书目计十七种。乙部见自变量居四部之首,其中又以《南越志》、诸种《异物志》、《异苑》《山海经》和《洞冥记》征引频次为高。沈怀远《南越志》后世散佚,唯凭诸书转引而得见其残貌,《北户录》正文、注文计引共十五次,《隋书·经籍志》归在杂史,《旧唐书·经籍志》则置其于史录地理类。《北户录》所引《异物志》记有杨孚《异物志》(《南裔异物志》《交州异物志》)、万震《南州异物志》和三条次不具名《异物志》。《隋书·经籍志》《旧唐书·经籍志》都将《异物志》归为史部地理类,将其视作地志类著述。“异物志”其实是汉唐间一类撰着的通称,其特征是多“枚举物性灵悟”,题名都含有“异物志”。诸家书录列载最早的是东汉杨孚所撰《异物志》(亦名《南裔异物志》《交趾异物志》《交州异物志》)。“异物志”的创作自汉时发端,大盛于魏晋六朝,至中晚唐段公路时虽犹得见,然其风气已渐衰微。凡所载记主要是南方也有及于南海、西南、西域地区的风俗物产,以志物为中心,广涉地理环境、历史传说、社会生产诸方面。是《北户录》虽然不以“异物志”为名,但其撰写的实质则同。博物之士对于前代《异物志》一类的地理书,对其中逸闻奇物、八荒之事往往多有追寻的志趣,也多有主动修撰这种图经、地志的热情和好尚,《娄地记》《风土记》《南雍州记》《聘北道里记》率皆此类。“凡此诸作,举足以羽翼正史,疏明往昔”,汉唐间的私家地理书既是一种知识传播和积累的手册,也是华夏文化圈在扩大过程中与异文化接触激荡所留下的痕迹,正可由见视野不断扩展中的天下、世界图像的构建。《北户录》是段公路作为一名华北士人进入“异域”的岭南地区“观化察时,周知民俗”之作,其择取志录的标准明确是“有异于中夏者”(陆希声语),因而在记述中往往将所见之物与“中国”相较,比以“北中”的凡三见(“鸡毛笔”条兔毫、“食目”条芜菁、“斑皮竹笋”条斑皮竹笋),比以“中夏”者亦三例(“象鼻炙”条供御陁国青象、“偏核桃”条占卑国偏核桃、“指甲花”条波斯耶悉弭花、白末利花)。这种有意识的比较,不仅在乎物产的有无,实际也是“中夏”与岭中乃至与异国外邦的区别的强化,进而凝结为文化之异的表征。从这个意义上讲,《北户录》留存和展现了中晚唐时华夏士人在与急剧扩大的外界的接触中,在异文化环境中(包括物质与精神),对我群—他群的划分和对自身文化价值的再认识。

另一方面,自《山海经》《神异经》以至《异物志》《北户录》,对异物的关注愈发占据中心地位,而山川道里等地理因素渐有减少,且其神话色彩日少,趋于核实存真。博而且信,亦由此欤?

其余地志和《异苑》《洞冥记》等杂史情况与之大体相类。

《北户录》征引丙部子录书二十五种,凡五十二次,《隋书·经籍志》《旧唐书·经籍志》外又五种。其中征引频次以郭义恭《广志》、张华《博物志》为多,此无赘言,另子录所引五行类、医术类书目特可注意。凡引五行类籍要计有《瑞应图》、孙氏《瑞应图》、熊氏《瑞应图》、《白泽图》、《淮南万毕术》。另有《灵芝图说》一种,虽不见诸二《志》,《隋书·经籍志》子部五行有《芝英图》一卷,未知是其同类否。段氏《北户录》言及祥瑞,凡亲历耳闻的有三事。一是宁普廉州有民进献赤白吉了。自三代以下,有赤乌、白雀一类征祥,诸家图谶典制有见,公路因以为可将其归于鸟兽中瑞。一是乾符初,有人献合欢笋于韦尚书,韦氏因命段公路作七字歌赞,此为草木之瑞。一是韦皋镇西蜀,有黄柑树生异果,韦皋以为祥瑞,欲表奏进呈。后得昝殷探明,实是误以虫孽为祥瑞。

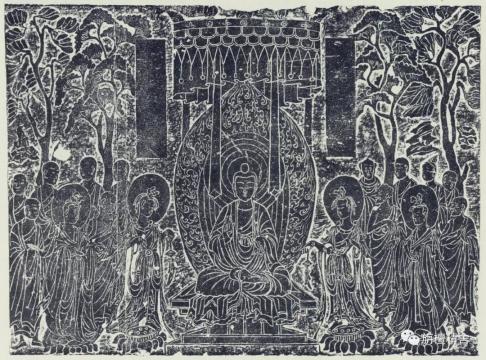

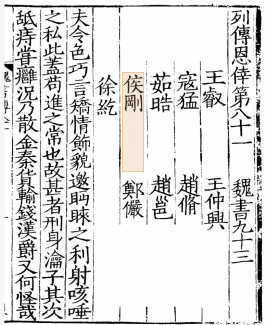

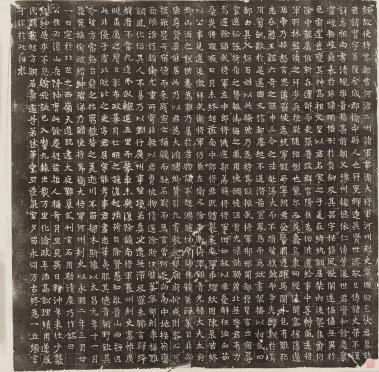

▴

敦煌绘本长卷P.2683《瑞应图》(局部)

法国国家图书馆藏

唐时瑞应列有等第,据《唐六典·尚书礼部》卷第四条陈,赤乌为上瑞,白雀为中瑞,段公路所欲补入的赤白吉了大约也在中瑞之列,献于韦尚书的合欢笋即木连理一类,等在下瑞。韦皋所见黄柑异果,以为“此奇果也,非臣下宜食”,准备拟表呈进,也是将其作为瑞应的一种,大约与秬秠、嘉禾、芝草等次相似,列属下瑞。段公路意图补附祥瑞,韦氏命公路作歌赞,韦皋谨守臣分,敬呈异实所表现出的对祥瑞的热情和对祥瑞与政治间关系的敏感,即是其时政治、社会风尚的体现。尽管自贞观初年,太宗有《诸符瑞申所司诏》,申明自龙凤龟麟等大瑞外不得滥奏,此后宪宗有《禁奏祥瑞及进奇禽异兽诏》,文宗下《令诸道不得奏祥瑞诏》,依唐典中、下瑞只能在年终由员外郎一并表奏,但基于祥瑞与政治权威间的密切关联,时人对瑞应往往保持着相当程度的热衷。

医术类书目引述以陈藏器《本草拾遗》见引最多。《本草拾遗》十卷,唐三元尹陈藏器撰,成书于开元二十七年(739),其书意在拾补《唐本草》所遗漏药物。观《北户录》对《本草拾遗》的引用,诸如鸺鹠拾人手爪、枭炙肥美为古人所重、象之本肉在鼻等,并非作为医方药术来推穷物理、考其物用,更多是以视作逸闻杂说的态度来搜罗众说,开人耳目,这也体现了博物学知识存布的广泛性。

《本草拾遗》亦述引博洽,李时珍云“(藏器)其所著述,博极群书,精核物类,订绳谬误,搜罗幽隐,自本草以来,一人而已。”粗略统计,其所引书一百一十六种,而比照《北户录》和《本草拾遗》引用文献,不难发现凡《北户录》所征引书目大部分也为百年前的医家陈藏器所征引。如此高的重合率,或者说对一大批文献的共同关注,意味着:第一,医术类,尤其是本草类书目的知识来源并不局限于医家自有的专门性传统,其来源范围涵盖甲乙丙丁四部经籍所代表的四大门类;第二,《本草拾遗》一类本草书与《北户录》一类带有博物学性质的著述具有共同的知识源群体,换言之,博物学知识除了专门性著作外,也由医方、本草等媒介来承载并扩散,并最终可能沉淀为人所习知的“常识”和“异闻”。前述诂训、小学类书目也常常扮演了同样李时珍在《历代诸家本草》中对陈藏器《拾遗》有一段精妙的评述:

肤谫之士,不察其该详,惟诮其僻怪。宋人亦多删削。岂知天地品物无穷,古今隐显亦异,用舍有时,名称或变,岂可以一隅之见,而遽讥多闻哉。如辟虺雷、海马、胡豆之类,皆隐于昔而用于今;仰天皮、灯花、败扇之类,皆万家所用者。若非此书收载,何从稽考。此本草之书,所以不厌详悉也。

这是针对《本草拾遗》在一定时期被视作言多“僻怪”,为正统医家诟病而发的议论。李濒湖以为世间物类不可胜数,有古所不知而后世发见、引入的,有人所习见而鲜知其功效的,加之有新名、别名、重名,所以往往混淆、遗漏,难以尽晓,而本草家的使命之一就是细加载录,“不厌详悉”,以使诸物可得“稽考”。陈藏器的“另类”知识取向,恰是他优出同侪的价值所在。这也从一个方面解释了医术类《本草拾遗》与博物类《北户录》在品物载录、知识来源方面何以有如此高的重合,《北户录》对《本草拾遗》的征引并非选择性或片段性的呈现,而是体现了《本草拾遗》的自身风格,这正源于陈氏、段氏某种共通的知识取向与追求。是以此固本草家言,实亦博物君子心声。

《北户录》所引拟可归于丁部集录的文献计十一种、十二次,另有二《经籍志》无载的有五种。“米饼”条正、注文合十六次引南朝笺状书启来讨论前朝单位语词的用法,也是段氏、崔氏目力广博的一个例子。

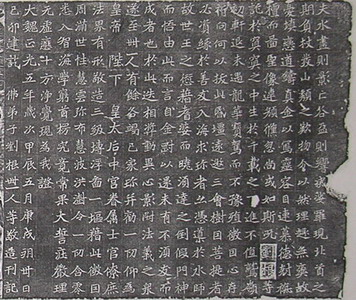

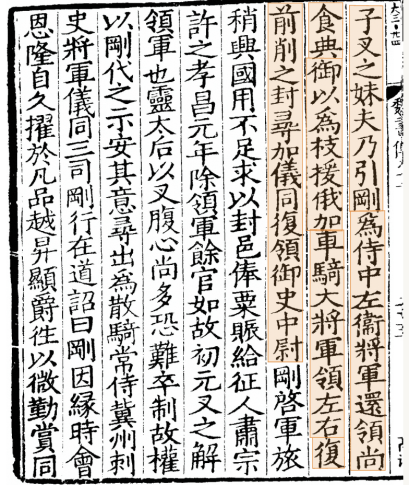

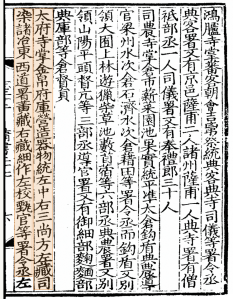

▴

北京石景山孔雀洞唐刻《佛本行集经》

此外段公路引道经二种:《真诰》《九微志》,佛经二种:《佛本行集经》《浴佛功德经》。史载段文昌赎先祖故第为浮屠祠。《酉阳杂俎》又记段文昌受持《金刚经》年久,信乎至诚。及刘辟自为剑南西川节度使,因与文昌相恶,文昌走避之,道遇异象相导从。后刘辟为乱事发,段文昌牵涉进反对刘辟的谋划中,图谋者被杀,而文昌因屡得异象示警终而逃脱。这两件事都被认为是段文昌笃信《金刚经》的果报。段成式则自言先后受持听解《平消御注》《大云疏》《青龙疏》等,并平素日日念诵书写,心既虔诚,用功又勤,史亦称其“尤深于佛书”。又《北户录》“指甲花”条:

愚详末利乃五印度华名,佛书多载之,贯花亦佛事也。

是段公路不仅知晓佛典,于释教名物也颇有了解,对佛教科仪也有相当程度的熟悉,其谙于内典、道经抑或由家学之渐染。

上述以《北户录》征引文献与《隋书·经籍志》《旧唐书·经籍志》相比对的做法,实际上是以博物学类知识与甲乙丙丁四部经籍为代表的四大门类知识这两种不同的知识范畴划分法相参验,考察两种不同角度的知识归类体系间的关系——两者呈现出广泛而又紧密的交织图景,在这个意义上,博物学正是古代中国知识与信仰世界的基底性要素之一,也是中国学术本源之一端。

二、曲尽万物:博物学知识的流布与联结

前取《北户录》引征篇目,方之《隋书》《旧唐书》二《经籍志》,得以浅探段氏的读书目类、知识崖略,借以窥视其博物之学知识构成的侧面。今又以段成式《酉阳杂俎》与《北户录》相参详,略有述论如下。

柯古《杂俎》条目卷帙数倍于《北户录》,其广博亦数倍于是《录》,差相比对,计有二三十处有关联的载记。如孙和为邓夫人取獭髓合药,由琥珀而成妆靥事,见在《北户录》“鹤子草”条,并注明引自王子年《拾遗记》,此事同见于《酉阳杂俎·黥》中,唯言辞稍微简略,也未明言其出处。又如䱤鱼为诸鱼生母,二书都有记载,唯《北户录》明言出自《异苑》,而《杂俎》则无。再如《酉阳杂俎》前集卷之十八《木篇》与《北户录》卷三“无名花”条:

娑罗,巴陵有寺,僧房床下忽生一木,随伐随长,外国僧见曰:“此娑罗也。”元嘉初,出一花如莲。(《酉阳杂俎·木篇》)

梁伍安贫《武陵记》云:“巴陵郡西有寺,寺房廊林下忽有树生,众僧移屋避之,晚更滋茂,莫有认者。外国沙门云是波罗蜜掷,常着花细白。永嘉四年,忽生一花,状似芙蓉。”(《北户录·无名花》)

文辞虽然有详略,外来语词中的译名也有差别,但二者同述一事,两文本有共同的来源,也明着可见。又《北户录》注明源出伍安贫《武陵记》,而《酉阳杂俎》无载。此兹举三例,其余二十来处与之大抵类似,往往《北户录》叙述稍详,且具明所引,而《酉阳杂俎》唯直陈其事。引述的详略与是否标明源流出处并非这里想讨论的重点,中国古时作书多有径取前人著述,删补改易为其所用,而不注写出处的。然而这里试图关注的是这样一些个体的、零碎的知识点可能以怎样的方式被汲取,可能通过怎样的途径传播。

▴

清拓《梵域娑罗图》

乾隆四十五年(1780)

纵220.7厘米,横102.5厘米

故宫博物院藏

段成式与段公路的关系,讫无明载。《新唐书·艺文志》云公路为段文昌之孙,陆心源言段公路乃成式之子,段安节的弟弟,则未知所凭何据。且疑《艺文志》注记段公路与段文昌的亲眷关系,也由陆希声《北户录序》“东牟段君公路,邹平公之孙也”而得。《太平寰宇记》卷145,襄州宜城县条记载了段成式曾居木香村别业,其时有异竹萌生,柯古摹写以送徐商,二人迭相酬唱。方南生在《段成式年谱》中将此事系于宣宗大中十三年(859)下。《北户录》“斑皮竹笋”条中段公路自言在襄州宜城木香村有庄墅,咸通初生异竹,并详细描摹其情状。懿宗继位在大中十三年农历八月,来年即改元咸通(860),两相比较,萌生异竹之事和事件发生的时间、地点,都可相合契。加之段成式在《酉阳杂俎》中曾屡次提及其家弟,则段柯古与段公路有父党之谊似亦不诬。

陆希声在《北户录序》中嘉赏段公路及受学“薅乎群籍之中,仡仡然有余力”,其中“群籍”或许并非只是泛泛而言。《旧唐书》称段成式“家多书史,用以自娱”,此段氏书藏或许即是其亲族举家习业的共同基底。须知彼时读书不若今下来源之广泛,士子习书固然有庠校监学,甚至可能进入秘阁通览天家籍要,但家室私有的书目笈册应当是士人自幼受学最为精熟的部分。族内有何种旧籍、长辈素喜何类书目,往往对于子孙群小颇有影响,进而可能形成共有的知识背景。段成式《寄余知古秀才散卓笔十管、软健笔十管书》有“窃以《孝经援神契》,夫子赞之,以拜北极;《尚书中候》,周公授之,以出元图。其后仲将稍精,右军益妙;张芝遗法,闾氏新规。其毫则景成愈于中山,麝柔劣于羊径。或得悬蒸之要,或传痛颉之方,起自蒙恬,盖取其妙”云云。《北户录》“鸡毛笔”条,段公路自下按语,首先引《博物志》所记蒙恬制笔,其次引《董仲舒答牛亨问》所言蒙恬造笔的情状,进而引《尚书中候》“龟负图,周公援笔写之”。或云,周公、蒙恬,笔之由来尚矣,其时世所熟知,乌足为怪。然而对一事物如何加以阐释,引用何种文献以为奥援,多非随意而为,往往可以透视出叙述者对这一物事所固有的观念认识,即所谓相关的知识背景;或者说,选择怎样的阐释方式,常与叙述者自身想要达到的特定目的有关,通过对阐释过程和方式的考察进而对这些都可能有所了解。换而言之,此类阐释不仅仅是对共识的铺陈,而且呈现出一种独特性,即便就“共识”而言,在某种程度上也可由之追寻其“圈层”与“系谱”。倘使考虑到段成式是段公路的父辈亲眷,并前《酉阳杂俎》与《北户录》相比较所见,其中或许有一“家学”承袭的可能。盖段公路所读家府藏书,柯古亦尝用心着力。柯古寓目既广,公路踵成其后。嗣后段公路撰着《北户录》时,凡所征引,往往也与段成式所见相同,因而有采摭同源的痕迹。甚或段公路的相关知见,可能并不直接来自群书众典,而是从段柯古的言谈、教谕和著述中得来。

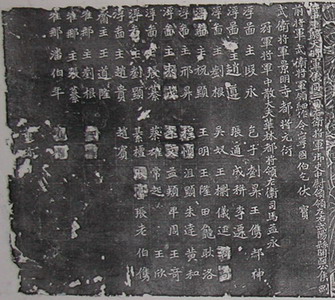

▴

敦煌佛爷庙湾魏晋壁画墓中的“河图”“洛书”图像

段成式父段文昌有《邹平公食宪章》,成式有《酉阳杂俎》,至公路有《北户录》,其家三世,可谓皆“博闻多见,曲尽万物之理者”。在这样一个家族内部,有共同的知识基底(“家多书史”),而段文昌、段柯古的言教、撰着在其中可能承担了一种有选择性的、导向性的知识传承“中介”的角色。

是则博物之学于中古士人间有此种家内承袭因循之传统欤?

《酉阳杂俎》而外,《岭表录异》也与《北户录》有相当之干连。《岭表录异》,《新唐书·艺文志》题撰者刘恂,计三卷。是书亡佚,后世有从《永乐大典》和他书中辑复者,今可见有鲁迅校勘本和商壁、潘博辑本二种。这两种书书前所引“《四库全书》本提要”为乾隆四十年(1775)五月进呈时所撰,题“总纂官庶子臣陆锡熊,侍读臣纪昀,纂修官主事臣任大椿”,今影印本《文渊阁四库全书》所收《岭表录异》书前所附提要则为乾隆四十一年(1776)五月由总纂官纪昀、陆锡熊、孙士毅和总校官陆费墀写进的。两者间差别有二:一则前提要云“马端临《文献通考》亦云(刘恂)昭宗时人”,后提要则作“陈振孙《书录解题》亦云(刘恂)昭宗时人”。检今本《直斋书录解题》,无收《岭表录异》,《文献通考》卷205《经籍三十二》有“《岭表录异》三卷,陈氏曰:唐广州司马刘恂撰,昭宗时人”,是马氏转引陈书,此可补今本《书录解题》阙佚。二则后提要于《录异》成书时代有一考辨,认为书中有称“唐昭宗”之处,既然称唐皇帝谥,那么此书修成应当晚在五代。此推测大致不差。

▴

《岭表录异》书影

乾隆刻本

《录异》与《北户录》间的关系,《岭表录异校补·序论》举了枹木、桄榔两个例子,以为刘恂或“从同一事物的同一方面对段公路所记进行了详细的补充”,或“写了段公路之不写”,这当然是刘氏在载记岭南风物方面所具有的独特价值和贡献。然而通贯比较两书,其文本间必定曾相参佐的痕迹颇为明显,兹举二例示之:

鹤子草,蔓花也。其花曲尘色,浅紫蒂,叶如柳而小短,当夏开。南人云是媚草,甚神,可比怀草、梦芝。采之曝干以代面靥,形如飞鹤状,翅羽觜距,无不毕备,亦草之奇者。草蔓上春生双虫,常食其叶。土人收于奁粉间,饲之如养蚕法。虫老不食而蜕为蝶,蝶赤黄色,女子佩之如细鸟皮,号为媚蝶。(《北户录·鹤子草》)

鹤子草,蔓生也。其花曲尘色,浅紫蒂,叶如柳而短。当夏开花。又呼为绿花绿叶。南人云是媚草,采之曝干,以代面靥,形如飞鹤,翅尾嘴足,无所不具。此草蔓至春生双虫,只食其叶。越女收于妆奁中。养之如蚕,摘其草饲之。虫老不食而蜕为蝶,赤黄色,妇人收而带之,谓之媚蝶。(《岭表录异·鹤子草》)

愚传闻贞元五年秋,番禺有海户犯盐禁者,避罪于罗浮山,深入至第十三岭,遇巨竹百千万竿,连亘严谷。竹围二十一寸,有三十九节,节长二丈,即由梧类也。海户因破之为篾,会罢,吏捕逐,遂挈而归。时有军人获一篾以为奇者,后献于刺史李复。复命陆子羽图而记之,亦资耳目之事一也。(《北户录·斑皮竹笋》)

贞元中,有盐户犯禁逃于罗浮山,深入第十三岭。遇巨竹万千竿,连亘岩谷。竹围皆二丈余,有三十九节,二丈许。逃者遂取竹一竿,破以为筏,会赦宥,遂掣以归。有人得一筏奇之,献于太守李复,乃图而纪之。(《岭表录异·罗浮山竹》)

比较两书对鹤子草、媚蝶和海户入罗浮深山遇巨竹的传闻的记述,同样的事物和事件而具有相同的性状和情节描述理固宜然,但诸如“其花曲尘色,浅紫蒂,叶如柳而小短”和“其花曲尘色,浅紫蒂,叶如柳而短”、“遇巨竹万千竿,连亘严谷”和“遇巨竹百千万竿,连亘岩谷”一类文辞细节的一致和叙述语句整体的相似,则昭示了二者间的转引袭抄关系。而在关于海户见罗浮巨竹的传闻记述之后,《北户录》引李复与陆羽的对答,意在说明天地间多有异形殊状的草木,罗浮巨竹不足为奇;《岭表录异》则记叙了刘恂所知的另外两种形体伟巨的竹子,也意在说明罗浮山巨竹并非全然罕有。这两段记叙尽管内容并不相同,看起来也只是提及了其他几种同样与常见者不同的巨形瑰状之物,似乎是简单的相似物的罗列。但这反映了两位作者因身在岭中,见识有所扩大——认为巨伟殊状之物也是山海间自然所有,以“异”为“不异”,更重要的是其间表现出的思路其实是相因循的,其解释的模式也相一致。

▴

南宋《离支伯赵图》

台北故宫博物院藏

《北户录》中其余如孔雀媒、鹧鸪、蚺蛇牙、蛤蚧、红蝙蝠、金龟子、乳穴鱼、水母、蚊母扇、鹅毛被、象鼻炙、鹅毛脡、无核荔枝、山橘子、偏核桃、香皮纸等条目在《岭表录异》中都有相对应的词句近似的载记。段公路游历岭南约在咸通、乾符年间,刘恂至昭宗朝为广州司马,其间有一二十年的差距,而前后所成二书颇有相似之处,是吴翌凤跋即云“(《北户录》)是与刘氏《岭表录异》同资考据”。此处无意于考究两书之间具有怎样的转抄引征关系,然而可以推想的是,《北户录》在撰成后的十余年间,在一定范围内得以流传,并在同为著录岭南风土的《岭表录异》中留下了痕迹,这也是博物君子间知识交流、承袭的一个例证。

《酉阳杂俎》《岭表录异》与《北户录》间千丝万缕的联系,在某种程度上也就是博物学知识在同一时代内纵向和横向流通的痕迹。向使以较长时段考之,愈能见其知识联结之层次。此兹举一例:

橄榄子,八九月熟,其大如枣。《广志》云:“有大如鸡子者,南人重其真味。”一说香口绝胜鸡舌香,亦堪煑饮,饮之能销酒。其树耸拔,其柯不乔。有野生者,高不可梯,但刻其根方数寸,内少许盐于中,一夕子皆落矣。今高凉有银坑橄榄子,细长多味,美于诸郡产者,其价亦贵于常者数倍也。愚按:《南越志》:“博罗县有合成树,树去地二丈,为三衢,东向一衢为木威,南向一衢为橄榄,西向一衢为玉文。”《广志》书此“橄榄”字。《南州异物志》作此“橄

”字。陈藏器云:“其木主䲅鱼毒。此木作檝,橃着䲅鱼皆浮出,其相畏如此。”人中䲅鱼肝子毒者必死也。

段公路关于橄榄的载记平实寻常,归纳起来不过:一、橄榄子的时令和形状;二、橄榄的味;三、橄榄能解酒;四、橄榄树的特征;五、纳盐采橄榄法;六、橄榄中的佳品;七、一树三木;八、“橄榄”字的异写;九、橄榄木解䲅鱼毒。然而回溯其知识的源流:

橄榄生南海浦屿间,树高丈余,其实如枣。三(二)月有花生,至八月方(乃)熟,甚香。(橄榄)木高大难采,以盐擦木身,则其实自落。(杨孚《异物志》)

自东汉以降,人们对橄榄所生的地域、树木和果实形态、花期以及纳盐采实法已经有了相当了解。

〔橄榄〕闽、广诸郡及缘海浦屿间皆有之。树高丈余,叶似榉柳。二月开花,八月成实,状如长枣,两头尖,青色。核亦两头尖而有棱。核内有三窍,窍中有仁,可食。

橄榄子,缘海浦屿间生。实大如轴头,皆反垂向下。实先生者向下,后生者渐高。(万震《南州异物志》)

至三国吴时,对橄榄的载记基本承袭《交州异物志》的记录,但在子实形态和其生长形态方面有特别细致的观察。

橄榄,生山中。实如鸡子,正青,甘美味成时,食之益善。始兴以南皆有之。南海常献之。(薛莹《荆扬已南异物志》)

橄榄子大如枣。二月花色,仍连着实,八九月熟。生食味酢,蜜藏乃甜美。交趾、武平、兴古、九真有之。(徐衷《南方草物状》)

从两晋至刘宋,对橄榄的认识中加入了关于味道,尤其是两种不同食法、加工方式的味道的记载。而且橄榄被作为方物,出现与南海交往的记录中。

橄榄,涩酒。(裴渊《广州记》)

南朝刘宋前后,橄榄与酒已被联系在一起。

《广志》曰:“橄榄,大如鸡子;交州以饮酒。”

《南方草物状》曰:“橄榄,子大如枣;大如鸡子。二月华色,仍连着实;八月九月熟。生食味酢,蜜藏仍甜。”

《临海异物志》曰:“余甘子如梭形。初入口,舌涩;酸饮水,更甘。大于梅实,核两头锐。呼‘余甘’‘柯榄’,同一果耳。”

《南越志》曰:“博罗县有‘合成树’,十围。去地二丈,分为三衢:东向一衢,木叶似练,子如橄榄而硬;削去皮,南人以为糁。南向一衢,橄榄。西向一衢,三丈——三丈树,岭北之候也。”

北魏贾思勰将此前诸家载记做了汇集,饮酒用橄榄载之甚明,只是未晓用于解酒或是调味,橄榄的别名“余甘”“柯榄”也被著录,此外一树三木的合成树也见记载。

橄榄木 解䲅鱼肝及子毒。(《本草拾遗》)

橄榄木解䲅鱼毒说见陈藏器《本草》。

橄榄子独根,树东向枝曰木威,南向枝曰橄榄。(段成式《酉阳杂俎》)

柯古《酉阳杂俎》承合成树的说法,但多了对橄榄独根的描述。

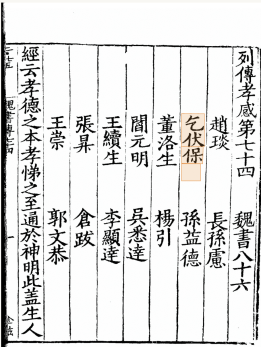

▴

文俶《金石昆虫草木状》中的泉州橄榄

回顾自东汉杨孚至中晚唐段公路关于“橄榄”知识的历代积累,橄榄的形性、味道、生长周期、采摘方法,橄榄木的生长特征,以及合成树、橄榄可解酒、橄榄木解毒等认识逐渐层迭,而《北户录》新补入了高凉银坑出上佳橄榄和“橄榄”字形异写两条信息。至《重修政和证类本草》,前述大部分信息都被收录,并又补入了其药性和药用法。

《北户录》对“橄榄子”的著录比较简单平实,而在简单平实之后,其认识的每一部分都可能经历了相当长时间的知识累积,而《北户录》的相关载记本身也作为关于橄榄认识的知识链条的一环而存在。关于《北户录》的考察,以及其与《酉阳杂俎》《岭表录异》关系的探讨展示了中晚唐时期博物学知识的承袭扩散、迭层累积。

三、博而且信:亲验时风的渐立

《北户录》在载记风物方面与杨孚《交州异物志》、万震《南州异物志》及沈怀远《南越志》、裴渊《广州记》一类私家地志性质相同,所记物类也多有重合,因而征引频仍。另一方面,与前述诸书比较,段氏著述也有其显著的特点——多有关于亲身参验的记录。

例如“蛤蚧”条中提到十二时虫,传闻此种异虫一日变十二色,另一种传说则更为神奇,即虫的头会随着时间推移变作十二般形象。这两种传闻又都见于较《北户录》撰着时间稍早的孟管《岭南异物志》和段成式《酉阳杂俎》。依孟管的记述,这其实是两种全然不同的异虫,一种会变色,且伤人致命,一种头会化形,不但不伤人,而且见之有喜,相同的不过是都生于南方,且随时辰而变化。而段成式所听闻的十二辰虫则与孟管所记载的第二种相同。需要注意的是,尽管段成式写明其从兄亲见,但就段柯古而言仍然属于传闻,而且载记某某经见、据某某得闻,事实上在《灵验记》一类著述中能找到源流。而《北户录》中既有“愚尝获一枚,闭于笼中翫之”云云,段公路依其亲身观察所见指出,这种虫只会变作黄褐赤黑四种颜色,而非传闻中的十二种色,并且认为虫首会变形的说法只是夸大其词。两种传闻中的异虫是否为同种虽然存疑,但段氏的观察说明了两点:第一,十二时虫变色有限,并没有十二色之多;第二,段氏所见的十二时虫不会变形。这就对传闻做了修正,较之单纯的异闻载录有所进步。

▴

居廉《野趣》(1875年 )

广州艺术博物院藏

又《岭南异物志》关于蚊子树的记载与《北户录》“蚊母扇”条引《南越志》都云有树生实,实化蚊而出,两处载记颇为相似,而段公路又据自己观察“愚验之亦有为蚊子者”,则基本能相合。尽管就我们今天的知识看来,这应该是蚊虫在树实中产卵,孵化而出,并非所谓果实化为飞虫,《南越志》《岭南异物志》的载记和段氏的观察都不正确,但段公路所记的意义在于,他通过自己的亲自验证肯定并补充了一项关于岭南“异物”的传说,这显得神奇而又可以信实。需要注意到,段公路作《北户录》是有意识地志录岭中有别于中夏的、中夏所无或罕见罕闻的物产风俗,其阅读对象——中夏之人对南方感到陌生而新奇。中晚唐之际,小说传奇的创作乃社会风潮所向,往往多搜罗异闻奇事,荒唐诡诞、滑稽诙谐,乃至訾毁前贤,都为一时喜闻乐见。然而倘若一味搜罗闻所未闻、耸人耳目的事故传说,终不免徒为谈端,唯资悠悠者之口实。事可考验,能核其实成为博物学另一面的追求。《北户录》的撰写一方面要介绍人所不习见的“异物异事”,一方面又要努力将自身与荒诞不经的编造相区别。段公路已经不满足于在“异域”的南方仅仅载记传说,于前人著述中寻摭例证,进而每每强调自己亲身所验:

生瑇瑁甲治毒有神效,“愚曾取解毒,立验”(通犀);养鹦鹉忌用手频繁触摸,犯者鹦鹉多病死,“愚亲验之”(鹦鹉瘴);段公路在高凉程次青山镇遇群猨,“因召猎者捕而养之”(绯猨);段氏在雷州对岸候舟船,亲见小儿驱拥巨蛇,又有群蛇相从(红蛇);传闻蛤蚧一年鸣叫一次,“验之非也”(蛤蚧);公路过悬藤峡,童子所折枝条其上缀有蛱蝶,“愚因登岸视之”(蛱蝶枝);《登罗山疏》中记有金光虫,“余偶得之,养玩弥日”(金龟子);公路自茂名归南海途中,亲历祭奠船神玄冥孟家的仪式,并作祝文(鸡骨卜);段氏所居襄阳宜城县木香村别墅中生异竹(斑皮竹笋)。如是种种,都能见到段公路亲验实践的痕迹。这种对“其着于录者,悉可考验”的强调,不但强调作者确然南游五岭,亲得闻见,连作序的陆希声也因曾从事岭南,可以“备核其实”,故而受其托付来为《北户录》的可信度背书。

▴

聂璜《海错图》中的玳瑁

如此求亲验求核实的风气在同时代的房千里《投荒杂录》和刘恂《岭表录异》中皆有所见。此略举两例:

新州西南诸郡,绝不产蛇及蚊蝇。余窜南方十年,竟不覩蛇。(《投荒杂录》)

海镜饥,则蟹出拾食,蟹饱归腹,海镜亦饱。余曾市得数个验之,或迫之以火,则蟹子走出,离肠腹立毙;或生剖之,有蟹子活在腹中,逡巡亦毙。(《岭表录异》)

他们游走于中晚唐中原王朝“治内”边缘与“化外”南疆,随着对岭南开发的日益推进,及其在南疆游历时日愈久,与当地接触愈深,其见识也愈广,所闻见的异事也愈多愈奇。记叙的物事愈“异”,也意味着记叙得愈“博”。在追求“博”的同时,又坚持着“信”的标准,以免坠入荒诞不经,徒于骇人耳目。因而亲验与实践无疑成为段公路辈记叙博而且“信”的强有力注脚。

段公路、房千里、刘恂辈身处“异文化”的南方,以尽可能翔实可靠的方式将“希闻异事”转陈于中夏,他们的亲验实践令这些“希闻异事”变得不“异”,即具有较高的可信度,这些信实可靠的“希闻异事”向中夏之民展示了一个神秘瑰丽的南方世界,而随着“希闻异事”的广泛传播和被接受,由希闻而习见,最终转变为人们关于绝少能够身临其境的远方世界的“常识”。而中夏与南疆的分界正在此辈的著述中变得生动而清晰,也由他们的著述最终模糊而淡化。以段公路、段成式为代表的中晚唐博物学者开拓并重视亲验的风气,强调“博而且信”的传统。这种对时贯今古、覆载六合的无涯之“知”的追寻和实践亲验的风尚相融合,共同参与了构筑近在遐迩又渺不可及的世界图景。