The Poetry of Feedback

Today, outside of a few specialized applications, the would-be metascience of cybernetics is remembered, if at all, only as a hazy prelude to modern computing and information technology. But in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s cybernetics was popular on a scale that might be difficult to appreciate today and enjoyed a nonspecialist audience that extended far and wide from the academic centers and military-industrial research centers where it was born. Books like Norbert Wiener's The Human Use of Human Beings and Gregory Bateson's Steps to an Ecology of Mind sold hundreds of thousands of copies, while cybernetic theorizations made plausible and significant contributions to economics and anthropology, business management theory and art criticism, psychoanalysis and linguistics, as well as core areas in the applied and theoretical sciences, which everyone expected would soon be completely transformed by such research. The status of cybernetics as the overarching future framework of not only the natural but also the social sciences (and even the arts) seemed virtually assured, even to its enemies. Martin Heidegger, for instance, thought this product of Anglo-American technocracy, born from the crucible of World War II and its rationalized barbarism, threatening enough that he would answer curtly with the single word "cybernetics" when asked by a Der Spiegel reporter in 1966, "And what takes the place of philosophy?"1

American literature during this period was saturated with cybernetic metaphors, concepts, and themes. In fact, many of the novels that would later come to form the canonical instances of postmodern literature are essentially built around cybernetic concepts such as information, entropy, feedback, and system—from the allegories of control in William Burroughs's Nova trilogy and Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano, to the melodramas of heat death and entropic decay in Philip K. Dick's Ubik and A Scanner Darkly and J. G. Ballard's short stories (to name a British writer); from the paradoxes of information and entropy in William Gaddis's JR and Thomas Pynchon's 1960s novels, to the thought of feedback and system in John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Robert Coover, and, later on, Don DeLillo.2 If you were a white man and interested in experimentation in prose fiction in the 1960s and 1970s, then you were probably writing about machines, entropy, and information. Beyond the domain of the novel, the breakdown and efflorescence of neo-avant-garde art in the late 1960s was in some sense superintended by a popular reception of cybernetic ideas as well as a more general worrying about media and medium. The 1970 "Information" show at MoMA, including work by many of the most recognizable figures of this period, is an index of the broad distribution of the cybernetic imaginary, which provided a primary conceptual framework for Robert Smithson, Hans Haacke, and Dan Graham; Vito Acconci, Allan Kaprow, Adrian Piper, Hélio Oiticica, and Yvonne Rainer, to name just a few, as well as the poets and writers of the period who were, in some sense, understood as conceptual and performance artists: Hannah Weiner, Madeline Gins, and Bernadette Mayer.3 Charles Olson made "feedback" a guiding metaphor for his compositional process, as did A. R. Ammons. Beyond the American literary and art scene, French structuralism and poststructuralism were, in many regards, elaborated through a reception of Anglo-American cybernetics—Jacques Lacan writes famously about cybernetics in his second seminar, as do Claude Levi-Strauss and Roland Barthes, and as would Jean Baudrillard, Jean-François Lyotard, Jacques Derrida, and Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari later on.4 Indeed, as Bernard Geoghegan notes, one of the explanations for the precipitous disappearance of cybernetics as a referent was its replacement by a set of poststructural concepts that were, to some extent, its progeny.

In a section of the The Human Use of Human Beings, Norbert Wiener bemoans the lack of a contemporary humanistic and scientific lingua franca of the sort that Latin once provided. The implication, throughout the book, is that cybernetics might provide this new common tongue for the complex, technological societies of the twentieth century. And although this vision never came to pass, among the conceptual artists, performers, poets, musicians, and dancers of downtown New York in the late 1960s and 1970s, cybernetic concepts functioned as a kind of lingua franca and were, in part, what enabled a person to write a poem one day, make an installation the next, and design a performance the day after that. Just as cybernetic concepts emerged at the boundaries of mathematics, physics, engineering, and biology—from the common efforts of various researchers brought together in government-sponsored research programs and conferences—cybernetically inflected concepts such as "system," "process," and "information" provided an interart grammar that allowed conceptual artists, musicians, dancers, and poets to engage in common projects, developing new aesthetic categories, such as "the happening" or "environment," by which these projects could be received.

Strange Bedfellows

How do we explain this development? How do we understand the broad appeal for artists of this "science of everything," gaining in popularity and clout such that, by the mid-1960s, it provided key conceptual frameworks for both the counterculture and the corporate, political elite, for neo-avant-garde artists, and government technocrats? Cybernetics is, in the formulation Norbert Wiener gives it, defined as the scientific study of "control and communication in the animal and machine."5 Its central concepts emerge, in part, from attempts by Wiener and others to develop self-correcting antiaircraft guns—in other words, guns that could track the movement of a plane and predict where it would be by the time an artillery shell reached it. This required a certain form of feedback whereby information received from an object—in this case, the target—produced a self-adjustment and a change in the "behavior" of the gun.6 Although the techniques for mechanical self-regulation date from the invention of the water clock and feature in devices as familiar as the household thermostat, one of the best examples of the servomechanical union of communication and action is cybernetician W. Ross Ashby's "homeostat." This is a device made from four interconnected electrical transistors such that the electrical output from one transistor becomes the electrical input of the other three. Each one of the four transistors has a number of settings that determines how it modulates inputs and turns them into outputs, and thus the number of possible combinations of inputs and outputs the machine can produce is exceedingly complex, yielding up tens of thousands of results. Despite their complexity, the results divide rather simply into either stable or unstable patterns. The input voltages for each transistor either settle around a single value or, alternately, fluctuate back and forth wildly, producing fluctuating outputs and a chaotic set of feedbacks between transistors. What makes this machine seem a plausible model for homeostasis and self-regulation, however, is that the thousands of possible unstable states lead, by design, to a stable one. If after a period of time the input voltages fail to settle on a single value, the transistor resets and randomly tries a new setting. It continues to reset until it finds a setting that leads to a stable input voltage. All of the transistors continue to reset until they find a range of settings that leads to stable inputs and outputs for each other. Thus, this is a self-stabilizing machine, what cyberneticians call a "hyperstable" device, capable of self-modulating through the mechanism of feedback, in response to changing inputs. Such devices provided, for many cyberneticians, a plausible portrait of how the body regulates its own temperature, how an animal learns from its behavior, how a corporation adapts to changing market conditions, and how a national economy corrects itself in the face of trade imbalances.7

Cybernetics was, of course, closely connected to technological developments in computing and telecommunications that were extremely important to the course of postwar society. In many ways, its ambition to unify the natural and social sciences, and even the humanities and the arts, is a relic of the massive cross-scientific endeavors of the war effort—the Manhattan Project, first and foremost—which organized disjointed university research studies into structures more common to the military and industry and which gave rise to numerous technologies with social and commercial applications. It is not surprising, then, that for many this science of control and communication promised a response to social and economic issues that seemed especially pressing. "Control" and "communication" were, of course, central preoccupations for societies whose economic policies were based on Keynesian "social planning," whose hierarchical, multilayered corporations raised new problems of management, and whose deskilled manufacturing system put control over the content and pace of production in the hands of a professional-managerial class. Cybernetics, unsurprisingly, appealed to corporate management, military engineers, or government technocrats, as it promised a more efficient and less violent means of managing complex processes.

What is more surprising, however, is the way that cybernetics appealed to the hippies, leftists, counterculturals, and bohemian artists of the period, whose ostensibly libertarian and communalist politics would put them in direct conflict with the managers and technocrats who were reading the same books. Despite its origins in military research and its ominous self-description as a science of control, cybernetics could often present itself as a holistic, organic mode of social regulation in line with fundamentally democratic values and premised on the empowerment and participation of all. As Fred Turner writes in his study of the cybernetic counterculture, it provided "a vision of a world built not around vertical hierarchies and top-down flows of power, but around looping circuits of energy and information."8 Cybernetics was therefore the lingua franca of people who thought the problems of the age arose from too much control as well as those who thought it arose from too little. While seen from the standpoint of the counterculture and certain parts of the New Left, cybernetics suggested the organizational form of a future postcapitalist society no longer based on domination and exploitation; to much more decidedly pro-capitalist elements it offered a set of mechanisms through which techniques of domination and exploitation could be perfected and rendered palatable. The power of cybernetics lay in its ability to dissolve oppositions, to transform a contest between opposed entities into the internal self-regulation of some larger entity that included both sides. As an example of the holistic view of cybernetics, Turner quotes the title poem of Richard Brautigan's All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, a book whose fifteen hundred copies were distributed for free on the streets of Haight-Ashbury in 1967, describing "a cybernetic ecology / where we are free of our labors / and joined back to nature." With the homologies that it establishes between human, animal, and machine, cybernetics provides the dissolution of conventional oppositions between labor and leisure, nature and culture, such that the poem can imagine "a cybernetic meadow / where mammals and computers / live together in mutually programming harmony."9

As a form of opposition to the organization of postwar societies that, paradoxically, would dissolve all opposition into "mutually programming harmony," the cybernetic imaginary in its countercultural setting was particularly appealing to corporate managers looking to allay the dissatisfactions and rebellions of their workers through the incorporation of worker-manager feedback loops. But cybernetic models were also appealing in their own right, beyond questions of morale, especially once conditions of profitability eroded in the 1960s and, seeking a way to cut costs, firms began to look for ways to trim the various managerial layers that had emerged as corporate structures became more elaborate and complex. Cybernetics seemed as if it would provide the solution to the inefficiencies and violence of autocratic management, shearing needless management and making "control" a technical rather than personal matter. This was the function not only of the specifically cybernetic management theories of people like Jay Forrester and Stafford Beer but, as Michael C. Jackson summarizes in a book on the topic, a general category of "systems thinking" within business management that "gave birth to strands of work such as 'organizations as systems,' general system theory, contingency theory, operational research, systems analysis, systems engineering and management cybernetics," all of which shared with cybernetics a tendency to view firms as adaptive, equilibrium-seeking entities.10

Cybernetics and the related disciplines it influenced therefore provided models of streamlining while responding positively, rather than merely repressively, to the newly prevalent critiques of capitalist work that emerged in the late 1960s, critiques that focused on qualitative rather than quantitative demands, targeting in particular the alienating, machinic, rote, and routinized character of deskilled blue-and white-collar labor. Visible already within influential books of the 1950s such as William Whyte's The Organization Man or Herbert Marcuse's One-Dimensional Man, such critiques were something of a commonplace by the middle of the 1960s, and as Thomas Frank and others have shown, you might encounter such views within the so-called establishment as well as on the countercultural margins.11

Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello call this qualitative challenge to work "the artistic critique" (as opposed to the wage-oriented "social critique") precisely because it percolates outward from the counterculture and the artistic avant-garde.12 Faced with the combination of the social and artistic critiques epitomized by the rebellion of May 1968 but in evidence throughout the period, firms sought to pit the two critiques against each other, engineering a form of pseudo-empowered, "flexible," and "self-managing" work that met the demands of the artistic critique (for authenticity, creative expression, diversity of tasks, participation in decision making, flexible hours, etc.) in a manner that allowed for a newly intensive exploitation, effectively eroding the previous gains of the workers' movement with regard to wages, workday length, and benefits. In short, the new self-directed employees would work much harder and longer than their predecessors. The meeting between cybernetics and the neo-avant-garde complicates this story slightly, since what we note is not the recuperation by capitalist firms of a set of purely external values, concepts, or ideas but rather a contest over the meaning of a set of ideas. Though cybernetics emerges with the military-industrial complex, it is transformed and put to new uses by artists and countercultural figures in the 1960s, who elaborate entirely new meanings within this field, meanings that eventually become the focus of corporate attempts to restructure in the face of the critical challenges raised by these meanings. In this sense, the artists and writers who participated in elaborating these cybernetic ideas did not simply share an elective affinity with the technocrats that they imagine themselves opposing. Rather, they were responding critically and correctively to the technocratic visions they encountered and imagining how those visions might provide the material for another social arrangement. Along with the various Pentagon-sponsored think tanks and university research programs, the art and writing of the period are one site where cybernetic ideas are elaborated, contested, transformed. Art and writing, in this sense, are experimental and speculative processes. They are laboratories of a sort, a "counter-laboratory," if you will. As we will see in the subsequent discussion of Hannah Weiner, by focusing on the interaction between artist and audience, writer and reader, or on the process rather than the object of art making, many of these works take as their vocation the active modeling of potential social relations, relations that both prefigure and contribute to the actual restructuring of the labor process that begins in the 1970s and intensifies during the 1980s.

The relationship is a bit more than prefiguration pure and simple and a bit less than direct causation, since the means of uptake by employers is complex and indirect, mediated in this case by the counterculture and the mass media and mass cultural forms that were fascinated by it. The political models of holistic collaboration, mutability, and participation elaborated by the love-ins, be-ins, and politicized festivals of the counterculture were based quite directly on the precedent set by the postwar neo-avant-garde, with its happenings, chance-based compositions, interventions into daily life, and ecstatic forms of derangement. And while it is true, for instance, as Thomas Frank has argued, that the "co-optation" theory that sees the mass culture lagging behind and eventually recuperating an original, revolutionary movement fails to acknowledge the presence of dissident, critical voices within the so-called establishment, voices that also bemoaned the rigid, bureaucratic, and authoritarian character of work life—though with entirely different ends in mind—I think the evidence is clear that, for the most part, these critical enunciations remained in an entirely theoretical register, oriented largely toward attitudes rather than concrete practices.13 Outside the avant-garde, first, and the counterculture, second, there were few practical examples of these participatory modes. For instance, although Douglas McGregor had written as early as 1957 about the need for a new "Theory Y" of management based on "job enlargement," "decentralization," and "participation and consultative management," he was intentionally vague about what this Theory Y might look like if implemented, suggesting that it was no more possible at that time than it was possible to build a nuclear power plant in 1945.14 Like nuclear power, Theory Y was foreseeable but not implementable. But at that very moment artists such as Allan Kaprow, Carolee Schneeman, and John Cage were already implementing their own Theory Y in the arts. It is notable that Fred Turner, in his study of counterculture and cyberculture, begins the story of Stewart Brand and the Whole Earth Network—so influential to the course of development of information technology and corporate structure—with Brand's involvement in the happenings of the Lower Manhattan art scene of the early 1960s.15 To be clear, I am not arguing that artists and writers are the source of the dissatisfactions at the root of the artistic critique; such experiences of alienation and anomie were widespread and well documented. Artists and writers provided a conceptual grammar and vocabulary—a set of reference points or coordinates with respect to which these dissatisfactions could be articulated—but they certainly did not create them.

Cybernetics at Work

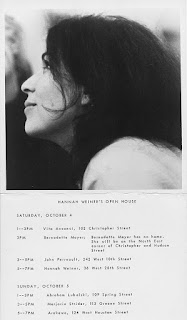

For an example of this incipient cybernetic grammar as one might have encountered it in the 1960s, consider the text Hannah Weiner wrote for her first "one-man show," Hannah Weiner at Her Job:

My life is my art. I am my object, a product of the process of self-awareness. I work part-time as a designer of ladies underwear to help support myself. I like my job, and the firm I work for. They make and sell a product without unnecessary competition. The people in the firm are friendly and fun to work with. The bikini pants I make sell for 49¢ and $1.00. If things can't be free, they should be as cheap as possible. Why waste time and energy to make expensive products that you waste time and energy to afford?

Art is live people. Self-respect is a job if you need it.16

This show took place in March 1970, among hundreds of similar happenings and performances. Best known for her later "clairvoyant" or "clair-style" poems, composed from the words that she began to see everywhere—on walls, on people's faces, in the air—Weiner was at the time of this show a poet associated with Fluxus and the downtown New York art scene. The quotation demonstrates one surprisingly anti-utopian consequence of the neo-avant-garde project of "art into life"; under conditions in which "art" has become synonymous with "life," then it has also become synonymous with "work," since most of life, for most people, means working.17 Going to work, then, counts as art, and making things or laboring becomes a secondary effect of the fundamentally artistic work of self-making and self-fashioning, where product and process are one. The gambit of such a project is that the merger of art and work will humanize and aestheticize the space of labor, here become a place where making and selling take place "without unnecessary competition."

The notion of self-production and self-objectification that we encounter in Hannah Weiner at Her Job—"I" as "object"—is very much a figuration of the cybernetic concept of "feedback." In cybernetics, any entity that regulates itself through the "circular causality" of feedback, where outputs produce inputs that subsequently modulate new outputs, can be thought of as self-aware at some basic level, even if it is a simple mechanical device or electrical circuit. In cybernetics, the very definition of an adaptive organism is that it can become its "own object," "a product of the process of the self-awareness." The statement could have been written by either Norbert Wiener or Hannah Weiner.

As discussed previously, cybernetics bases its notion of self-regulation on the mechanical devices called servomechanisms or, alternatively, "governors." Wiener coins the term "cybernetics" from the Greek word for "steersman" or "pilot," kybernetes, which is the root of "govern" in English.18 But what has not yet been adequately examined is the relationship posited between communication and these mechanisms of control. For cybernetics, there is essentially no difference between communication and control: "When I control the actions of another person, I communicate a message to him, and although this message is in the imperative mood, the technique of communication does not differ from that of a message of fact."19 To return to the example of the artillery guns, the action of the gun is itself an act of communication; it communicates (to itself) the degree to which its aim is correct or incorrect and modulates its own actions accordingly. Communication is not a disembodied system of signs but a performative and materialized chain of causes and effects. Indeed, communication is the very coherency of the organism itself. As Wiener writes in a chapter of The Human Use of Human Beings where he discusses the possibility of teleporting a person, organisms are fundamentally messages. It is the self-regulating pattern of information that gives them their identity, not the material of which they are composed, which is constantly switched out through various metabolic processes.20 One could therefore, at least hypothetically, duplicate a person through duplication of these information patterns. Communicable information is essence, for Wiener, a fact that might explain the appeal of these ideas to poets and others who worked with signs and symbols of one sort or another.

In the text that Weiner wrote for her next production—a collaborative, happening-like "Fashion Show Poetry Event"—communicable information is very much a formal essence, here identified with poetry, that ricochets back and forth between writers and artists, between makers of language and makers of things:

We communicated to the artists our generalized instructions. They translated instructions into sketches, models, and finally actual garments. The feedback (i.e., the garments) was then translated by us into fashion language. We have also translated this information into the language of press releases aimed at both the general and the fashion press and into the language of this theoretic essay.21

Weiner's contribution to the project was, as described by John Perreault, "a cape with hundreds of pockets proclaiming 'one should wear their own luggage.'"22 But the materialized "instructions" of the poets bore within them numerous pores or holes that emblematized the "difference between a description and that which this description appears to describe … the difference between a real fashion show and the imitation of a fashion show."23 This final turn of phrase indicates Weiner's uneasiness with or perhaps skepticism about perfect communicability. The pores of noise inside the message indicate its natural degradation, its tendency toward entropy, but also create a margin of error in which creative interpretation and misinterpretation might thrive.

First as salesperson, then as manager, Weiner during this period remains preoccupied with labor as much as with the mundane, everyday activities that fill up our waking hours. Weiner, it is clear, aims to bring the special resources of art to bear on labor in a way that humanizes it, makes it seem more tolerable and pleasant, based on cooperation rather than competition, abundance rather than scarcity, participation rather than hierarchy: for example, her piece World Works, where she modified a shop sign by writing "the word THE over WORLD WORKS."24 The addition of the article changes "works" from noun to verb, suggesting the presence of unnamed agents, workers. It thus demystifies the impersonal "works," but it also presents a certain assurance that things function as they should, that there is an invisible order that equilibrates the functioning of things:

I wanted to do World Works because I wanted to create the feeling that people all over the world were doing a related thing at a related time, although they would be doing it individually, without an audience and without knowledge of what others were doing. It is an act of faith. We have unknown collaborators.25

Weiner's description of her intentions with regard to this act of détournement is oddly reminiscent of contemporaneous descriptions of the powers of the market and the price mechanism, which in the formulations of a thinker like Friedrich Hayek effects a decentralized system of coordination, through which, without knowing it, private producers and workers together plan for the optimal allocation of scarce resources. "The marvel" of the price mechanism, writes Hayek,

is that in a case like that of a scarcity of one raw material, without an order being issued, without more than perhaps a handful of people knowing the cause, tens of thousands of people whose identity could not be ascertained by months of investigation, are made to use the material or its products more sparingly; i.e., they move in the right direction.26

For Hayek, the price mechanism is fundamentally a form of information distribution—he compares it to a "system of telecommunications"—that enables everybody to have the information they need under conditions in which it would be impossible for any one person to have all the information everyone needs, as in a command economy. The important difference is that for Hayek the coordinating information functions through competition, because each private producer is trying to minimize costs and earn the highest profit. World Works, on the other hand, imagines the coordination as collaborative rather than competitive.

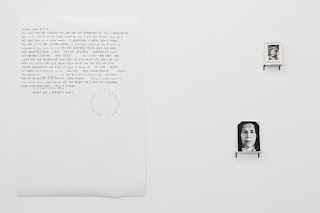

Installation view of "Hannah Weiner (1928–1997)," Kunsthalle Zürich. 2015. Photo: Gunnar Meier Photography.

In other conceptual and performance pieces from the same period, a different, much less positive "feeling" about labor emerges. This is especially true of Weiner's contribution to Street Works, a series of street exhibits put together by the Architectural League of New York. In Street Works IV (October 1969), for instance, Weiner hires a frankfurter wagon and distributes free wieners (a pun on her name). Although she intends to continue with the idea, established with Hannah Weiner at Her Job, that art is a form of self-distribution, a way of making the self available, and thereby transforming the self through a process of free giving and receiving, here the fact that "anything or anybody can have anything or anybody's name" takes on a sinister character.27 The gift economy made possible through the sharing of the product—the wiener that is a stand-in for Weiner herself—is troubled by the consequences of that very objectification, which she characterizes in her description of the project as embalmment: "Unfortunately wieners (and pastrami, bologna, preserved meats) contain sodium nitrite and sodium nitrate; one a coloring agent for otherwise gray meat, one an embalming fluid. Both have a depressing effect on the mind." Finally, in Street Works V (Dec. 21, 1969), Weiner cements the foregoing negative associations by playing the role of another type of street worker: "I stood on a street corner, or in a doorway, as if I were soliciting. Women do that in that neighborhood (3rd Ave & 13 St to 3rd Ave & 14th St). It is not a nice feeling at all."28

What distinguishes the first few examples, with their positive images of "fun and friendly" labor, from the latter examples, based on the unpleasant affects she associates with prostitution? One answer might lie in the term "self-respect." In the first examples, "the art" of "live people" allows for "self-respect," which means, I think, less a way of appreciating the self than a way of distinguishing it, making it into something unique and specific. There are forms of interaction between selves that deepen their self-respect or singularity, and then there are interactions that mean a loss of self and the total fungibility of all individuals, the reduction of individuals to a situation where "anything or anybody can have anything or anybody's name," where there is no difference between Wiener and Weiner, between Norbert, Hannah, or a slab of pastrami.

×

This text is an excerpt from chapter three of The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization by Jasper Bernes, published in May 2017 by Stanford University Press.

Jasper Bernes is author of two volumes of poetry, Starsdown (2007) and We Are Nothing and So Can You (2015), and a scholarly book, The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization (Stanford UP, 2017). Poems, essays, and other writings can be found in Modern Language Quarterly, Radical Philosophy, Endnotes, Lana Turner, The American Reader, Critical Inquiry, and elsewhere. Together with Juliana Spahr and Joshua Clover, he edits Commune Editions. He lives in Berkeley with his family.

| Evernote helps you remember everything and get organized effortlessly. Download Evernote. |

No comments:

Post a Comment